|

|

Conveyance of property in a public-private partnership for a “downtown development project”By Tyler MulliganPublished June 22, 2017Downtowns across America are experiencing a renaissance. Population growth in downtowns has outpaced growth in the broader regions in which those downtowns are located. North Carolina downtowns are likewise experiencing record growth. To capitalize on this renewed interest in downtowns, private developers and local governments are increasingly seeking to partner on relatively larger, coordinated development projects that involve construction of both public and private facilities. Often these public-private partnerships are necessary because the local government owns property downtown and needs a private partner to develop it. When a municipality (not a county) seeks to partner with a private developer for development of a downtown parcel involving construction of both public and private facilities, there is a statute designed just for that purpose: G.S. 160A-458.3 Downtown development projects. The statute makes some potentially confusing references to a variety of other statutes when authorizing disposition of real property and therefore requires some explanation. This post provides historical context for the statute and describes the property disposition procedures. Background on real property disposition generally We start with the general rule that, unless an exception is authorized by statute, North Carolina local governments are required to dispose of real property through competitive bidding procedures. Three procedures are available: sealed bid (G.S. 160A-268), upset bid (G.S. 160A-269), or public auction (G.S. 160A-270). The bidding process, theoretically, should yield the highest possible price. The law assumes that price is the most important factor to local governments; indeed, case law generally prohibits local governments from placing conditions on conveyances of property that will depress the price that a buyer would pay (Puett v. Gaston County). However, from time to time, compelling public interests led the General Assembly to enact exceptions to the competitive bidding requirement. “Downtown development projects” (DDPs) are one of the exceptions. Specifically, G.S. 160A-458.3(d) authorizes a city to convey “interests in property owned by it” in connection with a DDP in one of two ways:

In other words, in authorizing property disposition, the DDP statute refers to other statutes that had previously been enacted. Understanding the DDP statute therefore requires some understanding of the historical context for its enactment. Historical context for the Downtown Development Project (DDP) statute At the time the DDP statute was enacted, local governments were using federal community development funds to acquire property for the purpose of constructing public facilities or for conveyance to a private developer for redevelopment. G.S. 160A-456, enacted in 1975, authorized cities to employ the acquisition and conveyance powers provided to redevelopment commissions under the Urban Redevelopment Law (Article 22 of G.S. Chapter 160A), which granted broad development powers within designated blighted areas, including the use of eminent domain. A prior blog post, Using a Redevelopment Area to Attract Private Investment, provides an overview of the powers and procedures of the Urban Redevelopment Law. The land disposition powers in Urban Redevelopment Law are unique. Within a designated blighted redevelopment area, property can be sold through competitive bidding, but with an added bonus: conditions and restrictions can be placed on the sale to ensure the highest bidder will redevelop the property in accordance with the government approved redevelopment plan. G.S. 160A-514. However, to provide protection to property owners who could be subject to eminent domain in a blighted area, the Urban Redevelopment Law imposes significant procedural protections before its powers may be used. (The Attorney General ruled that the powers must be exercised in accordance with the procedures established in the Urban Redevelopment Law. North Carolina Legislation (1977)) Accordingly, a local government must first set up a redevelopment commission, designate a blighted redevelopment area, and adopt a redevelopment plan (no simple task)—and only then may it utilize the acquisition and conveyance powers of the Urban Redevelopment Law within the designated redevelopment area. The General Assembly eased the procedural burden for municipalities somewhat in 1977 by enacting G.S. 160A-457, which authorized cities to acquire property through voluntary purchase either as part of a federal community development program or independent of one, and without needing to comply with Urban Redevelopment Law. As the 1977 edition of North Carolina Legislation pointed out, the statute was designed to grant broad authority for voluntary acquisition of property, but there were no special sale procedures—property could only be disposed through “normal land disposition procedures.” In other words, local government property could be disposed through standard Article 12 disposition procedures, and property acquired through the Urban Redevelopment Law had to follow the special disposition procedures of that law. In 1983, the General Assembly added a new disposition procedure to G.S. 160A-457 (paragraph (4)). The provision allows real property “in a community development project area” to be sold to a redeveloper through private negotiation and sale (rather than standard Article 12 procedures), and covenants and restrictions can be placed in the deed to ensure that any future use will conform to the “community development plan.” The sale approval process involves detailed notice and hearing requirements and the property must be sold for no less than its appraised value. The 1983 edition of North Carolina Legislation hailed this addition as a “major breakthrough for cities by providing new flexibility in the disposition of land in community development programs…. In the past, municipal real property disposition statutes have required competitive bidding procedures be used…. By allowing land disposal by private negotiation and sale and allowing deed restrictions that apply to reuse of the land, the new law enables cities to sidestep two requirements that were widely perceived to be obstacles to effective community economic development programs.” Thus, as of 1983, this collection of statutes authorized a city to dispose of property associated with community development programs in any of the following ways:

DDP statute enacted Four years later, in 1987, the DDP statute was enacted. Its purpose, according to Professors Ducker and Green in the 1987 edition of North Carolina Legislation, was to allow municipalities to participate in “downtown development projects” using powers that previously “were restricted to larger cities that had obtained appropriate local legislation.” The intent of the statute was described by Ducker and Green as allowing “a city to work as a partner with private enterprises in planning, constructing, and managing buildings or complexes that may house both public and private facilities.” The kinds of capital projects envisioned by the statute, they continued, “have been encouraged by the federal government through its Urban Development Action Grant Program.” On the topic of property disposition, Ducker and Green explained that the required procedures were different depending on how the property was originally acquired. If the property was acquired while a municipality was exercising the power of a redevelopment commission, then the municipality “must dispose of it under the provisions of the urban redevelopment law (G.S. 160A-514).” If the property was acquired directly, the municipality “must dispose of it under its community development power (G.S. 160A-457).” Of course, cities already possessed those disposition powers—in that sense, the DDP statute merely clarified that cities could continue to utilize all of the disposition powers they had previously been granted. But did the DDP statute change anything in terms of property disposition? Yes, in two ways. First, the disposition powers were restated and applied “in connection with a downtown development project,” which by definition means that the powers are granted for any “capital project” in the “city’s central business district” involving at least one building and “including both public and private facilities.” The governing board must find that the unit’s ownership or participation in a “joint development project or of specific facilities within such a project” (the DDP) “is likely to have a significant effect on the revitalization of the jurisdiction.” The effect was to expand existing disposition powers to this new category of project. Second, the statute explicitly incorporated the disposition powers of G.S. 160A-457 but added the qualification that “Article 12 … does not apply to such dispositions.” Thus, the DDP statute further eased the existing procedural requirements for property disposition in connection with this new project category. These issues will be revisited later. To summarize the discussion thus far:

Bringing it all together With context established, it is possible to explain the real property disposition procedures authorized under the DDP statute. Disposition pursuant to Urban Redevelopment Law The DDP statute provides that “If the property was acquired while the city was exercising the powers, duties, and responsibilities of a redevelopment commission, the city may convey property interests pursuant to the “Urban Redevelopment Law” or any local modification thereof.” Urban Redevelopment Law conveyances are governed by G.S. 160A-514, subsection (c), where the following property disposal methods are authorized:

As already mentioned, the powerful innovation in property disposition in the Urban Redevelopment Law is that it provides special procedures for combining competitive bidding with restrictions and conditions on sale. Disposition “pursuant to G.S. 160A-457, and Article 12 … does not apply” The other property disposition method in the DDP statute states: “If the property was acquired by the city directly, the city may convey property interests pursuant to G.S. 160A-457, and Article 12 of Chapter 160A of the General Statutes does not apply to such dispositions.” Turning to G.S. 160A-457, that statute expressly authorizes disposition in one of the following ways:

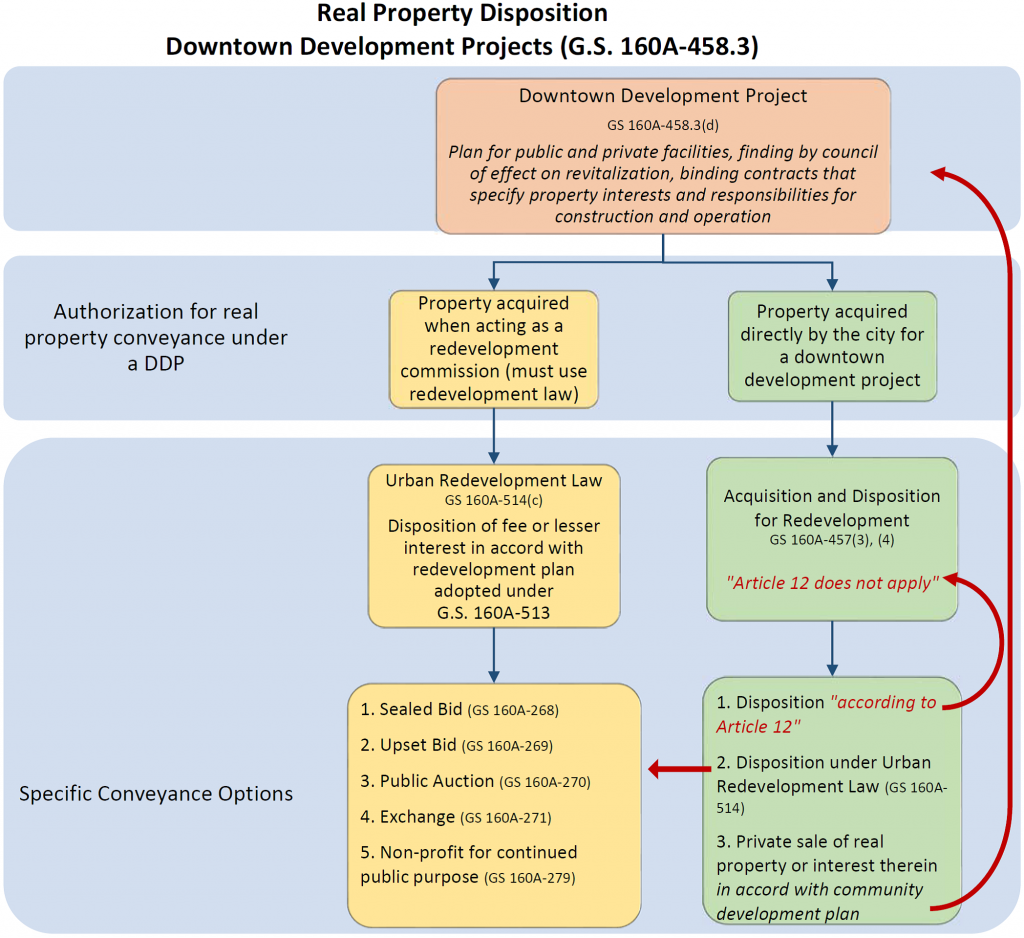

The DDP statute alters the G.S. 160A-457 procedures in two important ways. The first alteration is that Article 12 procedures do not apply. The DDP statute’s exemption from Article 12 was enacted later in time than G.S. 160A-457 and therefore can be deemed controlling over the reference to Article 12 in G.S. 160A-457. Orinoco Supply Co. v. Masonic & Easter Star Home, 163 NC 513 (1929). This is not to say that a local government is prohibited from using Article 12 procedures if it wishes. A local government is simply entitled to disregard those procedures and employ the special procedures in subsection (4) of G.S. 160A-457, which authorizes a private sale in a community development project area in accordance with the community development plan. The second alteration is that the DDP statute states that G.S. 160A-457 procedures may be used “in connection with a downtown development project.” How does this clause inform the G.S. 160A-457 procedure for private sale “in a community development project area … in accordance with the community development plan?” It cannot be the case that all of the requirements are additive, as that would tend to make the provision more difficult to use, not more flexible. An additive interpretation would mean that G.S. 160A-457 private sale procedures are permitted under the DDP statute only if all requirements are met as combined: (1) the project is a downtown development project as defined, and (2) the project is in a community development project area, and (3) the project adheres to a community development plan. The DDP statute was intended to provide more flexibility for cities, not less. Besides, the DDP statute already contains provisions that can loosely be described as a community development plan: a coordinated development with public and private facilities, a finding by council that the project will have a “significant effect on the revitalization of the central business district,” and binding contracts that specify the property interests of the city and developers, responsibilities of each for construction, and responsibilities of each for operation. Accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that the G.S. 160A-457 requirement for a community development plan can be fulfilled through the findings, plans, and binding contracts that are authorized by the DDP statute (and that are inevitably required as a practical matter for successful execution of a downtown development project). The disposition authority provided by the DDP statute is summarized in the following chart (thanks to Norma Houston):

Other questions Does an exemption from Article 12 disposition procedures mean that property can be conveyed at a discounted price? An exemption from Article 12 disposition procedures does not mean that the property can be sold at a discount. Gifts (such as discounts on property) to private entities are prohibited by Article 1, Section 32 of the North Carolina Constitution (for further legal analysis of that constitutional provision, see a blog post on the topic by my faculty colleague Frayda Bluestein). Further, the special conveyance procedure in G.S. 160A-457(4) explicitly provides that the consideration (or sale price) received for property cannot be less than the appraised value. However, it should be noted that when a statute permits a local government to impose covenants or restrictions on a conveyance, the law recognizes that the property’s value may be impaired by those restrictions, and appraisers may take the restrictions into account when determining appraised value. Can a city lease the public facility from the private developer rather than owning it, and still call the transaction a “downtown development project?” A downtown development project must include a “public facility,” but G.S. 160A-458.3 does not clarify whether a downtown development project can include public facilities that are leased from a private entity rather than publicly owned. Indeed, the statute contemplates arrangements for “ownership” and for “operation” of a downtown development project or specific facilities, but fails to mention leasing a public facility as lessee. The statute mentions leasehold interests only in the context of leasing publicly-owned air rights to a private developer, not leasing a public facility from a developer. This is in contrast to a similar statute enacted later, G.S. 143-128.1C Public-private partnership construction contracts, that contains similar language to G.S. 160A-458.3 but explicitly authorizes entering into a “lease as lessor or lessee.” G.S. 143-128.1C provides specific approval processes for capital and operating leases entered into by local governments, but the DDP statute is silent on entering a lease as lessee. If a city leases property from a developer for a public facility, would that qualify as a “downtown development project” under the statute? How significant is the General Assembly’s omission? Professor David Lawrence, on page 12 of his text on Local Government Property Transactions in North Carolina, points out that “North Carolina cases … hold or suggest that the authority to purchase or acquire property includes the authority to acquire a leasehold as well as a fee simple.” However, the question with respect to the DDP statute is not whether a city has authority to enter into a lease. The question is whether a city can lease space in a privately owned building and have that count as a “public facility” for purposes of the DDP statute, thus enabling a city to avail itself of the looser procedural requirements afforded by the statute. A principle of statutory interpretation suggests that the General Assembly’s omission carries meaning. Under the statutory interpretation principle of maxim expressio unius est exclusio alterius (“the expression of one thing is the exclusion of another”), the multiple references to public ownership and the simultaneous failure to mention leases of public facilities in the DDP statute could be interpreted as intentional, particularly in light of the explicit references to leases in G.S. 143-128.1C. This is not to suggest that the DDP statute prohibits a municipality from leasing a public facility in a downtown development project, but rather that a municipality should proceed cautiously before entering into a downtown development project in which a lease is the only property interest reserved for the municipality. It may be advisable for a municipality in a lease-only situation to follow the procedures of G.S. 143-128.1C, which explicitly provides for leases of public facilities. For more detail on G.S. 143-128.1C, see the blog post by my faculty colleague Norma Houston. This post has discussed competitive bidding for property disposition, but what about bidding of construction contracts for a downtown development project? Construction contract bidding goes beyond the scope of this post. However, G.S. 160A-458.3 does provide some relief from construction contract bidding requirements for private developers who construct public facilities as part of a downtown development project. Specifically, a private developer is authorized to construct public facilities in a downtown development project without following public contract bidding rules, “provided that city funds constitute no more than fifty percent (50%) of the total costs of the downtown development project.” For more detail on construction contract bidding, see the following blog posts by my faculty colleagues: |

Published June 22, 2017 By Tyler Mulligan

Downtowns across America are experiencing a renaissance. Population growth in downtowns has outpaced growth in the broader regions in which those downtowns are located. North Carolina downtowns are likewise experiencing record growth. To capitalize on this renewed interest in downtowns, private developers and local governments are increasingly seeking to partner on relatively larger, coordinated development projects that involve construction of both public and private facilities.

Often these public-private partnerships are necessary because the local government owns property downtown and needs a private partner to develop it. When a municipality (not a county) seeks to partner with a private developer for development of a downtown parcel involving construction of both public and private facilities, there is a statute designed just for that purpose: G.S. 160A-458.3 Downtown development projects. The statute makes some potentially confusing references to a variety of other statutes when authorizing disposition of real property and therefore requires some explanation. This post provides historical context for the statute and describes the property disposition procedures.

Background on real property disposition generally

We start with the general rule that, unless an exception is authorized by statute, North Carolina local governments are required to dispose of real property through competitive bidding procedures. Three procedures are available: sealed bid (G.S. 160A-268), upset bid (G.S. 160A-269), or public auction (G.S. 160A-270). The bidding process, theoretically, should yield the highest possible price. The law assumes that price is the most important factor to local governments; indeed, case law generally prohibits local governments from placing conditions on conveyances of property that will depress the price that a buyer would pay (Puett v. Gaston County).

However, from time to time, compelling public interests led the General Assembly to enact exceptions to the competitive bidding requirement. “Downtown development projects” (DDPs) are one of the exceptions. Specifically, G.S. 160A-458.3(d) authorizes a city to convey “interests in property owned by it” in connection with a DDP in one of two ways:

- Pursuant to the “Urban Redevelopment Law” if the property was originally acquired while the city was exercising the powers of a redevelopment commission.

- If the property was acquired by the city directly, the city may “convey property interests pursuant to G.S. 160A-457, and Article 12 of Chapter 160A of the General Statutes does not apply to such dispositions.”

In other words, in authorizing property disposition, the DDP statute refers to other statutes that had previously been enacted. Understanding the DDP statute therefore requires some understanding of the historical context for its enactment.

Historical context for the Downtown Development Project (DDP) statute

At the time the DDP statute was enacted, local governments were using federal community development funds to acquire property for the purpose of constructing public facilities or for conveyance to a private developer for redevelopment. G.S. 160A-456, enacted in 1975, authorized cities to employ the acquisition and conveyance powers provided to redevelopment commissions under the Urban Redevelopment Law (Article 22 of G.S. Chapter 160A), which granted broad development powers within designated blighted areas, including the use of eminent domain. A prior blog post, Using a Redevelopment Area to Attract Private Investment, provides an overview of the powers and procedures of the Urban Redevelopment Law.

The land disposition powers in Urban Redevelopment Law are unique. Within a designated blighted redevelopment area, property can be sold through competitive bidding, but with an added bonus: conditions and restrictions can be placed on the sale to ensure the highest bidder will redevelop the property in accordance with the government approved redevelopment plan. G.S. 160A-514.

However, to provide protection to property owners who could be subject to eminent domain in a blighted area, the Urban Redevelopment Law imposes significant procedural protections before its powers may be used. (The Attorney General ruled that the powers must be exercised in accordance with the procedures established in the Urban Redevelopment Law. North Carolina Legislation (1977)) Accordingly, a local government must first set up a redevelopment commission, designate a blighted redevelopment area, and adopt a redevelopment plan (no simple task)—and only then may it utilize the acquisition and conveyance powers of the Urban Redevelopment Law within the designated redevelopment area.

The General Assembly eased the procedural burden for municipalities somewhat in 1977 by enacting G.S. 160A-457, which authorized cities to acquire property through voluntary purchase either as part of a federal community development program or independent of one, and without needing to comply with Urban Redevelopment Law. As the 1977 edition of North Carolina Legislation pointed out, the statute was designed to grant broad authority for voluntary acquisition of property, but there were no special sale procedures—property could only be disposed through “normal land disposition procedures.” In other words, local government property could be disposed through standard Article 12 disposition procedures, and property acquired through the Urban Redevelopment Law had to follow the special disposition procedures of that law.

In 1983, the General Assembly added a new disposition procedure to G.S. 160A-457 (paragraph (4)). The provision allows real property “in a community development project area” to be sold to a redeveloper through private negotiation and sale (rather than standard Article 12 procedures), and covenants and restrictions can be placed in the deed to ensure that any future use will conform to the “community development plan.” The sale approval process involves detailed notice and hearing requirements and the property must be sold for no less than its appraised value. The 1983 edition of North Carolina Legislation hailed this addition as a “major breakthrough for cities by providing new flexibility in the disposition of land in community development programs…. In the past, municipal real property disposition statutes have required competitive bidding procedures be used…. By allowing land disposal by private negotiation and sale and allowing deed restrictions that apply to reuse of the land, the new law enables cities to sidestep two requirements that were widely perceived to be obstacles to effective community economic development programs.”

Thus, as of 1983, this collection of statutes authorized a city to dispose of property associated with community development programs in any of the following ways:

- through its normal land disposition procedures (Article 12),

- through the Urban Redevelopment Law’s procedures,

- or by private sale in a “community development project area” with conditions and restrictions on the sale to ensure the future use conforms with the “community development plan.”

DDP statute enacted

Four years later, in 1987, the DDP statute was enacted. Its purpose, according to Professors Ducker and Green in the 1987 edition of North Carolina Legislation, was to allow municipalities to participate in “downtown development projects” using powers that previously “were restricted to larger cities that had obtained appropriate local legislation.” The intent of the statute was described by Ducker and Green as allowing “a city to work as a partner with private enterprises in planning, constructing, and managing buildings or complexes that may house both public and private facilities.” The kinds of capital projects envisioned by the statute, they continued, “have been encouraged by the federal government through its Urban Development Action Grant Program.”

On the topic of property disposition, Ducker and Green explained that the required procedures were different depending on how the property was originally acquired. If the property was acquired while a municipality was exercising the power of a redevelopment commission, then the municipality “must dispose of it under the provisions of the urban redevelopment law (G.S. 160A-514).” If the property was acquired directly, the municipality “must dispose of it under its community development power (G.S. 160A-457).” Of course, cities already possessed those disposition powers—in that sense, the DDP statute merely clarified that cities could continue to utilize all of the disposition powers they had previously been granted.

But did the DDP statute change anything in terms of property disposition? Yes, in two ways. First, the disposition powers were restated and applied “in connection with a downtown development project,” which by definition means that the powers are granted for any “capital project” in the “city’s central business district” involving at least one building and “including both public and private facilities.” The governing board must find that the unit’s ownership or participation in a “joint development project or of specific facilities within such a project” (the DDP) “is likely to have a significant effect on the revitalization of the jurisdiction.” The effect was to expand existing disposition powers to this new category of project. Second, the statute explicitly incorporated the disposition powers of G.S. 160A-457 but added the qualification that “Article 12 … does not apply to such dispositions.” Thus, the DDP statute further eased the existing procedural requirements for property disposition in connection with this new project category. These issues will be revisited later.

To summarize the discussion thus far:

- Local governments must use Article 12 competitive bidding to dispose of real property and cannot impose restrictions on sale, unless an exception applies.

- In 1975, G.S. 160A-456 authorized municipalities to exercise the powers of a redevelopment commission under the Urban Redevelopment Law, to include special procedures for combining competitive bidding with restrictions and conditions on sale. However, all of the cumbersome urban redevelopment procedures must be followed prior to exercising the powers.

- In 1977, the General Assembly enacted G.S. 160A-457 to ease the procedural requirements for acquisition of property, making it unnecessary to rely on the Urban Redevelopment Law for acquisition. Disposition procedures were not loosened; land acquired under the new statute still had to be disposed pursuant to normal land disposition procedures (Article 12), and property acquired under the urban redevelopment law still had to be disposed according to urban redevelopment law procedures.

- In 1983, the General Assembly added subsection (4) to G.S. 160A-457 to allow for disposition of real property in a “community development project area” by private sale with conditions to ensure that development occurs “in accordance with the community development plan.” Special notice and hearing requirements are required, and the property must be sold for no less than appraised value.

- In 1987, the DDP statute was enacted. All of the above disposition powers were authorized “[i]n connection with a downtown development project.” Property acquired under the Urban Redevelopment Law still had to be disposed pursuant to that law’s procedures. For other property acquired by a city, the use of G.S. 160A-457 disposition procedures was authorized but “Article 12 … does not apply to such dispositions.”

Bringing it all together

With context established, it is possible to explain the real property disposition procedures authorized under the DDP statute.

Disposition pursuant to Urban Redevelopment Law

The DDP statute provides that “If the property was acquired while the city was exercising the powers, duties, and responsibilities of a redevelopment commission, the city may convey property interests pursuant to the “Urban Redevelopment Law” or any local modification thereof.” Urban Redevelopment Law conveyances are governed by G.S. 160A-514, subsection (c), where the following property disposal methods are authorized:

- Sealed Bid (160A-268)

- Upset Bid (160A-269)

- Public Auction (160A-270)

- Exchange (160A-271)

- Non-profit for public purpose (160A-279)

As already mentioned, the powerful innovation in property disposition in the Urban Redevelopment Law is that it provides special procedures for combining competitive bidding with restrictions and conditions on sale.

Disposition “pursuant to G.S. 160A-457, and Article 12 … does not apply”

The other property disposition method in the DDP statute states: “If the property was acquired by the city directly, the city may convey property interests pursuant to G.S. 160A-457, and Article 12 of Chapter 160A of the General Statutes does not apply to such dispositions.” Turning to G.S. 160A-457, that statute expressly authorizes disposition in one of the following ways:

- In “accordance with the procedures of Article 12,”

- In accordance with G.S. 160A-514 of the Urban Redevelopment Law, as described above,

- Or “at private sale” for property interests “in a community development project area … in accordance with the community development plan.”

The DDP statute alters the G.S. 160A-457 procedures in two important ways. The first alteration is that Article 12 procedures do not apply. The DDP statute’s exemption from Article 12 was enacted later in time than G.S. 160A-457 and therefore can be deemed controlling over the reference to Article 12 in G.S. 160A-457. Orinoco Supply Co. v. Masonic & Easter Star Home, 163 NC 513 (1929). This is not to say that a local government is prohibited from using Article 12 procedures if it wishes. A local government is simply entitled to disregard those procedures and employ the special procedures in subsection (4) of G.S. 160A-457, which authorizes a private sale in a community development project area in accordance with the community development plan.

The second alteration is that the DDP statute states that G.S. 160A-457 procedures may be used “in connection with a downtown development project.” How does this clause inform the G.S. 160A-457 procedure for private sale “in a community development project area … in accordance with the community development plan?” It cannot be the case that all of the requirements are additive, as that would tend to make the provision more difficult to use, not more flexible. An additive interpretation would mean that G.S. 160A-457 private sale procedures are permitted under the DDP statute only if all requirements are met as combined: (1) the project is a downtown development project as defined, and (2) the project is in a community development project area, and (3) the project adheres to a community development plan. The DDP statute was intended to provide more flexibility for cities, not less. Besides, the DDP statute already contains provisions that can loosely be described as a community development plan: a coordinated development with public and private facilities, a finding by council that the project will have a “significant effect on the revitalization of the central business district,” and binding contracts that specify the property interests of the city and developers, responsibilities of each for construction, and responsibilities of each for operation. Accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that the G.S. 160A-457 requirement for a community development plan can be fulfilled through the findings, plans, and binding contracts that are authorized by the DDP statute (and that are inevitably required as a practical matter for successful execution of a downtown development project).

The disposition authority provided by the DDP statute is summarized in the following chart (thanks to Norma Houston):

Other questions

Does an exemption from Article 12 disposition procedures mean that property can be conveyed at a discounted price?

An exemption from Article 12 disposition procedures does not mean that the property can be sold at a discount. Gifts (such as discounts on property) to private entities are prohibited by Article 1, Section 32 of the North Carolina Constitution (for further legal analysis of that constitutional provision, see a blog post on the topic by my faculty colleague Frayda Bluestein). Further, the special conveyance procedure in G.S. 160A-457(4) explicitly provides that the consideration (or sale price) received for property cannot be less than the appraised value. However, it should be noted that when a statute permits a local government to impose covenants or restrictions on a conveyance, the law recognizes that the property’s value may be impaired by those restrictions, and appraisers may take the restrictions into account when determining appraised value.

Can a city lease the public facility from the private developer rather than owning it, and still call the transaction a “downtown development project?”

A downtown development project must include a “public facility,” but G.S. 160A-458.3 does not clarify whether a downtown development project can include public facilities that are leased from a private entity rather than publicly owned. Indeed, the statute contemplates arrangements for “ownership” and for “operation” of a downtown development project or specific facilities, but fails to mention leasing a public facility as lessee. The statute mentions leasehold interests only in the context of leasing publicly-owned air rights to a private developer, not leasing a public facility from a developer. This is in contrast to a similar statute enacted later, G.S. 143-128.1C Public-private partnership construction contracts, that contains similar language to G.S. 160A-458.3 but explicitly authorizes entering into a “lease as lessor or lessee.” G.S. 143-128.1C provides specific approval processes for capital and operating leases entered into by local governments, but the DDP statute is silent on entering a lease as lessee. If a city leases property from a developer for a public facility, would that qualify as a “downtown development project” under the statute? How significant is the General Assembly’s omission?

Professor David Lawrence, on page 12 of his text on Local Government Property Transactions in North Carolina, points out that “North Carolina cases … hold or suggest that the authority to purchase or acquire property includes the authority to acquire a leasehold as well as a fee simple.” However, the question with respect to the DDP statute is not whether a city has authority to enter into a lease. The question is whether a city can lease space in a privately owned building and have that count as a “public facility” for purposes of the DDP statute, thus enabling a city to avail itself of the looser procedural requirements afforded by the statute.

A principle of statutory interpretation suggests that the General Assembly’s omission carries meaning. Under the statutory interpretation principle of maxim expressio unius est exclusio alterius (“the expression of one thing is the exclusion of another”), the multiple references to public ownership and the simultaneous failure to mention leases of public facilities in the DDP statute could be interpreted as intentional, particularly in light of the explicit references to leases in G.S. 143-128.1C. This is not to suggest that the DDP statute prohibits a municipality from leasing a public facility in a downtown development project, but rather that a municipality should proceed cautiously before entering into a downtown development project in which a lease is the only property interest reserved for the municipality. It may be advisable for a municipality in a lease-only situation to follow the procedures of G.S. 143-128.1C, which explicitly provides for leases of public facilities. For more detail on G.S. 143-128.1C, see the blog post by my faculty colleague Norma Houston.

This post has discussed competitive bidding for property disposition, but what about bidding of construction contracts for a downtown development project?

Construction contract bidding goes beyond the scope of this post. However, G.S. 160A-458.3 does provide some relief from construction contract bidding requirements for private developers who construct public facilities as part of a downtown development project. Specifically, a private developer is authorized to construct public facilities in a downtown development project without following public contract bidding rules, “provided that city funds constitute no more than fifty percent (50%) of the total costs of the downtown development project.” For more detail on construction contract bidding, see the following blog posts by my faculty colleagues:

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.