|

|

Student Corner: Exploring Form-Based CodesBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished April 23, 2015Form-based codes (FBC), an approach to zoning that emphasizes design over use, are an increasingly popular tool for municipalities to have in their repertoire as they consider shaping the future development of their communities and built environment. FBC are becoming more widely adopted as cities and towns seek to match development with an increasing preference for walkable, mixed-use, and more urban places that characterize what is popularly referred to as traditional neighborhood development. This blog post will explore the perceived advantages of FBC and how more compact development, a cornerstone of FBC, can help to enhance the tax base while reducing infrastructure costs for municipalities. First, what exactly does form-based coding mean? According to the Form-Based Codes Institute the definition of a form-based code is: “a land development regulation that fosters predictable built results and a high-quality public realm by using physical form (rather than separation of uses) as the organizing principle for the code. A form-based code is a regulation, not a mere guideline, adopted into city, town, or county law. A form-based code offers a powerful alternative to conventional zoning regulation.” History The modern archetype for FBC originates from when Duany Plater-Zyberk designed a new type of code for Seaside, Florida in 1982. The Seaside Urban Code was an attempt to replicate the traditional neighborhood development patterns of the early 20th century. Instead of concentrating on land uses as the primary mode of regulating development, the Seaside plan focused on the massing of buildings and design of the public realm. This spawned the beginning of the New Urbanism moment, and formed the foundation for champions of FBC. In 2003, Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company released their SmartCode model which introduced the now somewhat ubiquitous Rural-Urban Transect, and provides a generalized base from which form-based codes are built on. Although FBC have become popular over the last decade or so, they have been around since the 1980s and 1990s. Across the country, many cities both large and small have adopted FBC. According to the White & Smith Planning and Law Group, “In the mid-1990s, several smaller communities in North Carolina—including Huntersville, Davidson, Belmont and Cornelius, completely replaced their zoning regulations with complete form-based codes.” A study within the last several years identified at least eighteen different municipalities in North Carolina that have either replaced their code with FBC or have significant elements and/or districts that fit the requirements of FBC. FBC Overview Conventional Euclidean zoning is oriented around the regulation of land uses. It has also led to the prevalence of dimensional parameters such as floor-to-area ratios, dwelling units per acre, setbacks, height restrictions, parking requirements, etc. These parameters and concepts can be difficult to comprehend, leading to discontinuous, incompatible and segregated development. FBC attempt to correct this incongruity by creating a regulating plan based on the community’s ideals for an integrated physical form and public realm. More specifically, FBC focus on the street and building types, building materials, build-to lines, number of floors, and percentage of built site frontage. Developing a FBC involves community participation to develop the development goals for the community. FBC often become very specific to the needs and design interests of the community. The following are some generalized goals that often come out of a public FBC process and inform the details of the code:

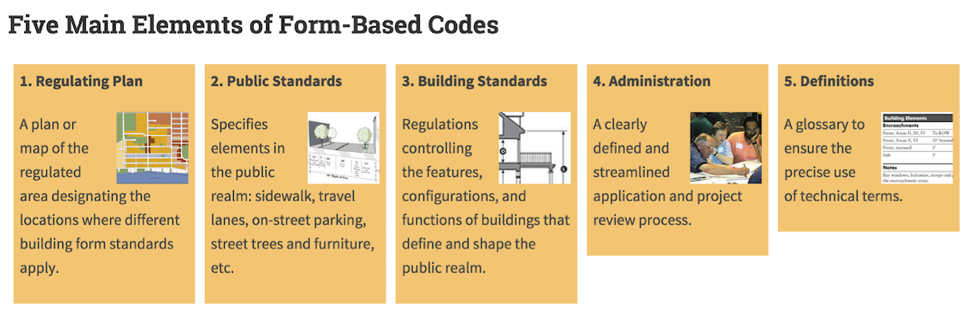

In terms of implementation, the Form-Based Codes Institutes recommends that all FBC include five main elements: They also suggest several other elements that are also important to consider for your community and its needs:

Potential FBC Benefits

Common FBC Misconceptions Even though FBC have been around for several decades, there are still some common misconceptions about FBC and the implications for your community. Below is a summarized list of the Top 10 misconceptions about form-based codes from Tony Perez (director of form-based coding for Opticos Design Inc.) and Better Cities and Towns. For his full explanation of each misconception click this link.

The list is a good reminder that each municipal should tailor their FBC to the particulars of their community. It is also important to remember that while FBC is primarily focused on the built form and public realm, it doesn’t necessarily need to disregard restrictions for uses or other traditional dimensional standards or design guidelines. In this sense, municipalities can find a “hybrid” approach that best suits their goals and wishes for future development. What are your experiences with form-based codes? Is this something you have implemented or are considering implementing in your community? Ben Lesher is a graduate student in both the Master of City and Regional Planning program and the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is also a Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. |

Published April 23, 2015 By CED Program Interns & Students

Form-based codes (FBC), an approach to zoning that emphasizes design over use, are an increasingly popular tool for municipalities to have in their repertoire as they consider shaping the future development of their communities and built environment. FBC are becoming more widely adopted as cities and towns seek to match development with an increasing preference for walkable, mixed-use, and more urban places that characterize what is popularly referred to as traditional neighborhood development. This blog post will explore the perceived advantages of FBC and how more compact development, a cornerstone of FBC, can help to enhance the tax base while reducing infrastructure costs for municipalities.

First, what exactly does form-based coding mean? According to the Form-Based Codes Institute the definition of a form-based code is: “a land development regulation that fosters predictable built results and a high-quality public realm by using physical form (rather than separation of uses) as the organizing principle for the code. A form-based code is a regulation, not a mere guideline, adopted into city, town, or county law. A form-based code offers a powerful alternative to conventional zoning regulation.”

History

The modern archetype for FBC originates from when Duany Plater-Zyberk designed a new type of code for Seaside, Florida in 1982. The Seaside Urban Code was an attempt to replicate the traditional neighborhood development patterns of the early 20th century. Instead of concentrating on land uses as the primary mode of regulating development, the Seaside plan focused on the massing of buildings and design of the public realm. This spawned the beginning of the New Urbanism moment, and formed the foundation for champions of FBC. In 2003, Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company released their SmartCode model which introduced the now somewhat ubiquitous Rural-Urban Transect, and provides a generalized base from which form-based codes are built on.

Although FBC have become popular over the last decade or so, they have been around since the 1980s and 1990s. Across the country, many cities both large and small have adopted FBC. According to the White & Smith Planning and Law Group, “In the mid-1990s, several smaller communities in North Carolina—including Huntersville, Davidson, Belmont and Cornelius, completely replaced their zoning regulations with complete form-based codes.” A study within the last several years identified at least eighteen different municipalities in North Carolina that have either replaced their code with FBC or have significant elements and/or districts that fit the requirements of FBC.

FBC Overview

Conventional Euclidean zoning is oriented around the regulation of land uses. It has also led to the prevalence of dimensional parameters such as floor-to-area ratios, dwelling units per acre, setbacks, height restrictions, parking requirements, etc. These parameters and concepts can be difficult to comprehend, leading to discontinuous, incompatible and segregated development. FBC attempt to correct this incongruity by creating a regulating plan based on the community’s ideals for an integrated physical form and public realm. More specifically, FBC focus on the street and building types, building materials, build-to lines, number of floors, and percentage of built site frontage. Developing a FBC involves community participation to develop the development goals for the community. FBC often become very specific to the needs and design interests of the community. The following are some generalized goals that often come out of a public FBC process and inform the details of the code:

- Create a public realm that invites pedestrian usage encouraging social interaction and safety

- Promote a critical mass and mixture of uses that support each other

- Encourage the use of community appropriate and high-quality materials and construction methods

- Leverage existing natural resources and community assets

- Respect and replicate existing architectural characteristics and heritage of the community

In terms of implementation, the Form-Based Codes Institutes recommends that all FBC include five main elements:

They also suggest several other elements that are also important to consider for your community and its needs:

- Architectural Standards – Regulations controlling external architectural materials and quality.

- Landscaping Standards – Regulations controlling landscape design and plant materials on private property as they impact public spaces.

- Signage Standards – Regulations controlling allowable signage sizes, materials, illumination, and placement.

- Environment Resource Standards – Regulations controlling issues such as storm water drainage and infiltration, development on slopes, tree protection, solar access, etc.

- Annotation – Text illustrations explaining the intentions of specific code provisions.

Potential FBC Benefits

- Community participation creates buy-in from the community and ensures that development is guided by the goals of the community.

- Function follows form — development is driven by the community interest and sense of place versus micromanagement of function or uses.

- FBC offer greater flexibility for developers and allow for the ability to match appropriate uses to market conditions while still controlling the impact on the community.

- FBC encourages more pedestrian traffic and alternative modes of transportation (non-auto centric).

- Produces more efficient development helping to increase the tax base while reducing infrastructure and public services costs.

- Studies have shown that there are public health benefits associated with compact development.

- FBC allows for more organic building design and aesthetic character.

Common FBC Misconceptions

Even though FBC have been around for several decades, there are still some common misconceptions about FBC and the implications for your community. Below is a summarized list of the Top 10 misconceptions about form-based codes from Tony Perez (director of form-based coding for Opticos Design Inc.) and Better Cities and Towns. For his full explanation of each misconception click this link.

- FBC always dictates architecture.

- FBC must be applied citywide.

- FBC is a template that you have to make your community conform to.

- FBC is too expensive.

- FBC is only for historic districts.

- FBC isn’t zoning and doesn’t address land use.

- FBC results in “by-right” approval and eliminates “helpful thinking by staff.”

- FBC results in “high-density residential.”

- FBC requires mixed-use in every building regardless of context or viability.

- FBC can’t work with design guidelines, and complicates staff review of projects.

The list is a good reminder that each municipal should tailor their FBC to the particulars of their community. It is also important to remember that while FBC is primarily focused on the built form and public realm, it doesn’t necessarily need to disregard restrictions for uses or other traditional dimensional standards or design guidelines. In this sense, municipalities can find a “hybrid” approach that best suits their goals and wishes for future development.

What are your experiences with form-based codes? Is this something you have implemented or are considering implementing in your community?

Ben Lesher is a graduate student in both the Master of City and Regional Planning program and the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is also a Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.