|

|

Student Corner: Waste Not, Want Not: Local Financing Options for Renewable Energy from Swine Waste in North CarolinaBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished May 6, 2014

What is anaerobic digestion?

NC Regulatory Framework to Promote Electricity Production from Swine Waste North Carolina has sought to promote adoption of such technologies through a Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Portfolio Standard (REPS). This policy tool, used by many states, requires that utilities generate a set percentage of their annual electricity production from renewable sources; North Carolina is the only state with a renewable portfolio standard for swine waste. Meeting the REPS requirement for swine waste would not only provide a new renewable energy source and reduce odors from swine farms, it would also generate new economic activity as systems are installed and brought into operation. Previous research by a student team in UNC’s Department of City and Regional Planning found that bringing 39 swine biogas systems online, enough to meet the first stage of the REPS requirement, would have a one-time impact on the state’s economy of $155.9 million in new economic output from system construction and an ongoing impact from operations of up to $12.9 million annually (UNC Chapel Hill, 2013). Despite the regulatory framework and the economic and environmental benefit to be gained from these systems adoption is slow. To date only nine on-farm anaerobic digestion systems exist in North Carolina out of hundreds of potential farms. The upfront installation costs are high and these technologies are still seen as new and unproven by farmers, potential investors, and lenders. Project Financials are the Primary Barrier to System Adoption While there are technological and knowledge barriers around anaerobic digester systems on swine farms, these are minor in comparison to the economic barriers (Kramer & Bilek, 2013). Kramer and Bilek found that, ultimately, if there is money to be made from capturing swine biogas, the industry will adapt to take advantage of this opportunity. At this stage the technology is still very costly and installation costs are high. Capital costs vary by farm size from an estimated $375 to $145 per swine head (Fryberger, 2014). Currently, the funding tools to support anaerobic digestion primarily exist at the federal and state levels. Funding sources include voluntary and mandatory carbon markets, tradable renewable energy certificates, and a host of loan and grant programs available through federal agencies such as the US Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency. This is good news in that swine biogas programs are eligible under a number of funding sources; however, the diversity of options and their individual requirements increases the complexity of system design. The Database for State Incentives for Renewable Energy (DSIRE) is a well-maintained source for finding available funding tools by area and project type. What can local governments do to encourage anaerobic digestion projects in their region?

Assistance can be provided to on-farm systems through traditional techniques such as economic development grants and revolving loan funds. In 2009 the state legislature also authorized local governments to fund renewable energy and energy efficiency projects through property assessed clean energy (PACE) loan financing. This tool allows a special assessment on the property to be used as the repayment source for the original loan. To date, no local governments in NC have established either a revolving loan fund or a PACE financing program for renewable energy. In the end, AD systems must provide a significant level of revenue on an ongoing basis to keep project stakeholders invested in the system. Upfront assistance can help a project get off the ground but it must be used in conjunction with revenue boosting strategies in order to keep systems running for the long term. Carbon markets are a promising way of achieving this, as is adding other waste streams into the digester, which boosts its efficiency. Building Economic Development Potential through Renewable Energy Promoting anaerobic digestion on hog farms will provide new revenues to farmers, stimulate new industries in eastern North Carolina, and mitigate the odor impacts from existing farms. For hog-producing counties in eastern North Carolina these technologies will improve community quality of life and boost economic development potential. These projects are complex technologically and financially; however, local governments can play a key role in convening the necessary stakeholders to overcome these barriers. Carolyn Fryberger is a Master’s student in UNC’s Department of City and Regional Planning focusing on community and economic development. This post is based on her master’s paper written for the Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise at UNC-Chapel Hill. References Kramer, J. & Bilek, A. (2013). Anaerobic Digestion on Swine Operations: Assessing Current Barriers and Future Opportunities. Energy Center of Wisconsin. Retrieved from http://pigconnect.uwex.edu/files/2013/01/ad-swine-ops-jan-2013.pdf Fryberger, C. (2014). Waste Not, Want Not: Financing Swine Biogas Systems in Eastern North Carolina (Master’s Paper). University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning, Chapel Hill, NC. UNC Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning Economic Development Workshop. (Fall 2013). Identifying Opportunities and Impacts for New Uses of Hog Waste in Eastern North Carolina. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. |

Published May 6, 2014 By CED Program Interns & Students

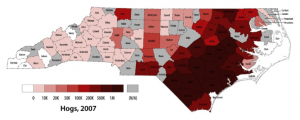

Eastern North Carolina is home to the densest industrial swine farming activity in the world. The pork production industry is foundational to the eastern North Carolina economy, accounting for 11,821 jobs and over $200 million in wages (UNC Chapel Hill, 2013). This activity comes with a cost, however, as high concentrations of swine waste can take a toll on environmental quality, public health, and property values in neighboring communities. The current waste management approach, termed ‘lagoon and spray’, involves collecting waste in open lagoons and intermittently spraying it on adjacent fields as the lagoon fills. Anaerobic digestion technology offers a waste management solution that can help to mitigate these community impacts while creating new forms of revenue from on-farm electricity production. Ultimately, these technologies can increase community quality of life and improve local economic development potential.

Eastern North Carolina is home to the densest industrial swine farming activity in the world. The pork production industry is foundational to the eastern North Carolina economy, accounting for 11,821 jobs and over $200 million in wages (UNC Chapel Hill, 2013). This activity comes with a cost, however, as high concentrations of swine waste can take a toll on environmental quality, public health, and property values in neighboring communities. The current waste management approach, termed ‘lagoon and spray’, involves collecting waste in open lagoons and intermittently spraying it on adjacent fields as the lagoon fills. Anaerobic digestion technology offers a waste management solution that can help to mitigate these community impacts while creating new forms of revenue from on-farm electricity production. Ultimately, these technologies can increase community quality of life and improve local economic development potential.

What is anaerobic digestion?

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a chemical process that takes advantage of naturally occurring bacteria to breakdown organic wastes. During this process gasses are released and collected which can then be burned to fuel a generator or purified to become natural gas or vehicle fuel. The digesters installed on farms can either be a conversion of their existing waste lagoon or a standalone unit. Other forms of organic waste from on and off the farm can mixed into the digester to boost overall productivity.

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a chemical process that takes advantage of naturally occurring bacteria to breakdown organic wastes. During this process gasses are released and collected which can then be burned to fuel a generator or purified to become natural gas or vehicle fuel. The digesters installed on farms can either be a conversion of their existing waste lagoon or a standalone unit. Other forms of organic waste from on and off the farm can mixed into the digester to boost overall productivity.

NC Regulatory Framework to Promote Electricity Production from Swine Waste

North Carolina has sought to promote adoption of such technologies through a Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Portfolio Standard (REPS). This policy tool, used by many states, requires that utilities generate a set percentage of their annual electricity production from renewable sources; North Carolina is the only state with a renewable portfolio standard for swine waste.

Meeting the REPS requirement for swine waste would not only provide a new renewable energy source and reduce odors from swine farms, it would also generate new economic activity as systems are installed and brought into operation. Previous research by a student team in UNC’s Department of City and Regional Planning found that bringing 39 swine biogas systems online, enough to meet the first stage of the REPS requirement, would have a one-time impact on the state’s economy of $155.9 million in new economic output from system construction and an ongoing impact from operations of up to $12.9 million annually (UNC Chapel Hill, 2013).

Despite the regulatory framework and the economic and environmental benefit to be gained from these systems adoption is slow. To date only nine on-farm anaerobic digestion systems exist in North Carolina out of hundreds of potential farms. The upfront installation costs are high and these technologies are still seen as new and unproven by farmers, potential investors, and lenders.

Project Financials are the Primary Barrier to System Adoption

While there are technological and knowledge barriers around anaerobic digester systems on swine farms, these are minor in comparison to the economic barriers (Kramer & Bilek, 2013). Kramer and Bilek found that, ultimately, if there is money to be made from capturing swine biogas, the industry will adapt to take advantage of this opportunity. At this stage the technology is still very costly and installation costs are high. Capital costs vary by farm size from an estimated $375 to $145 per swine head (Fryberger, 2014).

Currently, the funding tools to support anaerobic digestion primarily exist at the federal and state levels. Funding sources include voluntary and mandatory carbon markets, tradable renewable energy certificates, and a host of loan and grant programs available through federal agencies such as the US Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency. This is good news in that swine biogas programs are eligible under a number of funding sources; however, the diversity of options and their individual requirements increases the complexity of system design. The Database for State Incentives for Renewable Energy (DSIRE) is a well-maintained source for finding available funding tools by area and project type.

What can local governments do to encourage anaerobic digestion projects in their region?

- Stakeholder Coordination – These projects involve many different stakeholders, many of whom do not have established relationships. A high level of coordination is needed between these entities to ensure good project design, access to funding sources, and connections to markets (for electricity as well as for tradable environmental attributes such as carbon credits). Local governments can convene working groups with members of these distinct interests to begin conversations around implementing anaerobic digesters on area farms. Key stakeholders at the local level include:

- Farmers

- Credit Unions

- Renewable Energy Systems Integrators

- Electrical Utilities

- Other organic waste producers

- Cooperative Extension

- Highlighting Success Stories – While anaerobic digestion (AD) technology on swine farms is relatively new, there are 9 existing systems in North Carolina. Highlighting these stories of success through engaging stakeholders in tours of these operations and profiling successful projects in local forums will help build awareness and reduce perceived risk. AgSTAR, a joint effort between the US Department of Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency, maintains a database and profiles of existing anaerobic digestion projects.

- Local Funding Options – Local governments can also get directly involved in project financing. In addition to the environmental and public health benefits of anaerobic digestion, research suggests that converting open hog waste lagoons to closed AD systems will boost neighboring residential property values, in turn boosting local property tax revenues (UNC, 2013). This benefit to local governments may be a justification for providing some incentive to local farms to adopt AD technologies. Additionally, the improved quality of life and environmental quality in neighboring communities will ultimately attract new businesses and residents as the community impacts of hog farming are mitigated through odor reduction.

Assistance can be provided to on-farm systems through traditional techniques such as economic development grants and revolving loan funds. In 2009 the state legislature also authorized local governments to fund renewable energy and energy efficiency projects through property assessed clean energy (PACE) loan financing. This tool allows a special assessment on the property to be used as the repayment source for the original loan. To date, no local governments in NC have established either a revolving loan fund or a PACE financing program for renewable energy.

In the end, AD systems must provide a significant level of revenue on an ongoing basis to keep project stakeholders invested in the system. Upfront assistance can help a project get off the ground but it must be used in conjunction with revenue boosting strategies in order to keep systems running for the long term. Carbon markets are a promising way of achieving this, as is adding other waste streams into the digester, which boosts its efficiency.

Building Economic Development Potential through Renewable Energy

Promoting anaerobic digestion on hog farms will provide new revenues to farmers, stimulate new industries in eastern North Carolina, and mitigate the odor impacts from existing farms. For hog-producing counties in eastern North Carolina these technologies will improve community quality of life and boost economic development potential. These projects are complex technologically and financially; however, local governments can play a key role in convening the necessary stakeholders to overcome these barriers.

Carolyn Fryberger is a Master’s student in UNC’s Department of City and Regional Planning focusing on community and economic development. This post is based on her master’s paper written for the Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise at UNC-Chapel Hill.

References

Kramer, J. & Bilek, A. (2013). Anaerobic Digestion on Swine Operations: Assessing Current Barriers and Future Opportunities. Energy Center of Wisconsin. Retrieved from http://pigconnect.uwex.edu/files/2013/01/ad-swine-ops-jan-2013.pdf

Fryberger, C. (2014). Waste Not, Want Not: Financing Swine Biogas Systems in Eastern North Carolina (Master’s Paper). University of North Carolina Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning, Chapel Hill, NC.

UNC Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning Economic Development Workshop. (Fall 2013). Identifying Opportunities and Impacts for New Uses of Hog Waste in Eastern North Carolina. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.