|

|

Strengthening Resilience in North Carolina’s CommunitiesBy Brian DabsonPublished December 6, 2016Hurricane Matthew and its aftermath underscore the urgent need to find ways to encourage communities to think differently about how they prepare for disasters and how they can become more resilient. Part of this is having data and information that can spark realistic conversations about a community’s future. Another part is having the tools to turn these conversations into concrete actions to improve long-term resilience. This is the focus of a research project on community and regional resilience underway at the School of Government in conjunction with colleagues at the University of Missouri. Back in September 1999, North Carolina was hit by Hurricane Floyd. Some $3.5 billion in damages were inflicted on the state’s communities including the destruction of over 4,000 homes that were uninsured or under-insured. Hurricane Floyd also revealed significant weaknesses in available flood hazard data and mapping. One year later, the State of North Carolina entered into an agreement with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) known as the Cooperating Technical State agreement – the first in the nation. This gave the state the primary responsibility for preparing Flood Insurance Rate Maps for all North Carolina communities for the National Flood Insurance Program. The agreement called for updating and digitizing data for new flood hazard maps so as to improve forecasting and floodplain management. It also heralded closer cooperation and coordination across multiple Federal and start agencies. Since then, North Carolina has felt the impact of five more hurricanes that have been designated as major disasters, the latest of which was Hurricane Matthew in October 2016. The final damage figures for Hurricane Matthew will not be available for some time, although current estimates are in excess of $2 billion. FEMA, as of December 1, 2016, had approved nearly 27,000 applications for individual assistance amounting to over $80 million. The heavy rainfall that accompanied the hurricane was at historic levels with some places experiencing 14-15 inches in 24 hours. This led to severe flooding in all five river basins, with 200 to 500 year floods in Robeson, Columbus, Cumberland, Duplin, Johnston, Wilson, Green, Edgecombe, and Bertie Counties. The experience of the National Flood Insurance Program and its associated efforts to engage communities in preparing for and mitigating disasters provides just one indication of the enormity of the task. In North Carolina, 130,487 flood insurance policies were in force (as of September 2015), a nearly 4 percent reduction from the previous year. Adjusting for the number of households, North Carolina was 13th in the nation with just 3.45 percent of households covered. The result, according to preliminary estimates, is that 70 percent of buildings damaged by Hurricane Matthew were uninsured or under-insured. The response to Hurricane Matthew from Federal, state, and local governments, and from the voluntary sector has been exemplary, with very strong leadership from the Governor, North Carolina Emergency Management, and FEMA. But is clear that the post-Hurricane Floyd agreement, although it led to major improvements in the ability to predict impacts on communities, was not sufficient to protect many communities from devastating floods, or to convince residents and businesses to take greater responsibility for their own resilience in the face of disastrous events. As recovery efforts continue and the cost in lives, livelihoods, and properties are tallied, the question arises: what can be done to better protect our communities? Or to put in another way, what can be done to make our communities more resilient? The Rockefeller Foundation’s Judith Rodin describes the task this way: There is no question that building resilience must become a priority for us all… we need a keener awareness of the threats we face, greater ability to withstand and survive the disruptions we can’t avoid, and a deeper commitment and broader capacity to resume functioning so we don’t suffer debilitating loss or even collapse. We can no longer accept our vulnerabilities or ignore the threats we live with. Nor can we devote such great amounts of resources to recovering from disasters that could have been prevented or responded to more effectively. Nor can we continue to delude ourselves that things will get back to normal one of these days. They won’t.” Rodin, J. (2014) The Resilience Dividend. New York: PublicAffairs The research project on community and regional resilience has already led to some early outcomes:

Future blogs will describe the thinking behind economic, social, infrastructure, and environmental resilience and vulnerability, and will look at some of the critical questions facing local governments, such as: How much does improving resilience cost? Who is responsible for long-term recovery?

|

Published December 6, 2016 By Brian Dabson

Hurricane Matthew and its aftermath underscore the urgent need to find ways to encourage communities to think differently about how they prepare for disasters and how they can become more resilient. Part of this is having data and information that can spark realistic conversations about a community’s future. Another part is having the tools to turn these conversations into concrete actions to improve long-term resilience. This is the focus of a research project on community and regional resilience underway at the School of Government in conjunction with colleagues at the University of Missouri.

Back in September 1999, North Carolina was hit by Hurricane Floyd. Some $3.5 billion in damages were inflicted on the state’s communities including the destruction of over 4,000 homes that were uninsured or under-insured. Hurricane Floyd also revealed significant weaknesses in available flood hazard data and mapping. One year later, the State of North Carolina entered into an agreement with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) known as the Cooperating Technical State agreement – the first in the nation. This gave the state the primary responsibility for preparing Flood Insurance Rate Maps for all North Carolina communities for the National Flood Insurance Program. The agreement called for updating and digitizing data for new flood hazard maps so as to improve forecasting and floodplain management. It also heralded closer cooperation and coordination across multiple Federal and start agencies.

Since then, North Carolina has felt the impact of five more hurricanes that have been designated as major disasters, the latest of which was Hurricane Matthew in October 2016. The final damage figures for Hurricane Matthew will not be available for some time, although current estimates are in excess of $2 billion. FEMA, as of December 1, 2016, had approved nearly 27,000 applications for individual assistance amounting to over $80 million. The heavy rainfall that accompanied the hurricane was at historic levels with some places experiencing 14-15 inches in 24 hours. This led to severe flooding in all five river basins, with 200 to 500 year floods in Robeson, Columbus, Cumberland, Duplin, Johnston, Wilson, Green, Edgecombe, and Bertie Counties.

The experience of the National Flood Insurance Program and its associated efforts to engage communities in preparing for and mitigating disasters provides just one indication of the enormity of the task. In North Carolina, 130,487 flood insurance policies were in force (as of September 2015), a nearly 4 percent reduction from the previous year. Adjusting for the number of households, North Carolina was 13th in the nation with just 3.45 percent of households covered. The result, according to preliminary estimates, is that 70 percent of buildings damaged by Hurricane Matthew were uninsured or under-insured.

The response to Hurricane Matthew from Federal, state, and local governments, and from the voluntary sector has been exemplary, with very strong leadership from the Governor, North Carolina Emergency Management, and FEMA. But is clear that the post-Hurricane Floyd agreement, although it led to major improvements in the ability to predict impacts on communities, was not sufficient to protect many communities from devastating floods, or to convince residents and businesses to take greater responsibility for their own resilience in the face of disastrous events.

As recovery efforts continue and the cost in lives, livelihoods, and properties are tallied, the question arises: what can be done to better protect our communities? Or to put in another way, what can be done to make our communities more resilient? The Rockefeller Foundation’s Judith Rodin describes the task this way:

There is no question that building resilience must become a priority for us all… we need a keener awareness of the threats we face, greater ability to withstand and survive the disruptions we can’t avoid, and a deeper commitment and broader capacity to resume functioning so we don’t suffer debilitating loss or even collapse. We can no longer accept our vulnerabilities or ignore the threats we live with. Nor can we devote such great amounts of resources to recovering from disasters that could have been prevented or responded to more effectively. Nor can we continue to delude ourselves that things will get back to normal one of these days. They won’t.”

Rodin, J. (2014) The Resilience Dividend. New York: PublicAffairs

The research project on community and regional resilience has already led to some early outcomes:

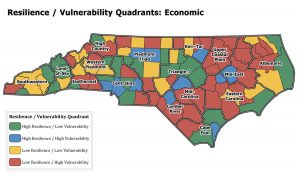

- With funding from the National Science Foundation, a set of measurements have been developed for resilience and vulnerability for every county in the United States. These look at four dimensions: economic, social, infrastructure, and environmental. The map shows how these play out in North Carolina for economic resilience and vulnerability.

- In 2015, a guide to regional resilience was prepared for the National Association of Development Organizations (NADO) to help regional development organizations and councils of government better understand how they can improve regional resilience. The materials can be accessed at planningforresilience.com.

Future blogs will describe the thinking behind economic, social, infrastructure, and environmental resilience and vulnerability, and will look at some of the critical questions facing local governments, such as: How much does improving resilience cost? Who is responsible for long-term recovery?

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.