|

|

Community Resilience Has Many Faces…Part 2By Brian DabsonPublished March 7, 2017The research project on community and regional resilience at the School of Government aims to help communities think differently about how they prepare for disasters and how they can become more resilient, providing data and information that can spark realistic conversations about a community’s future. This blog looks at some of the main elements that determine resilience and vulnerability in North Carolina’s counties. Previous blogs, Strengthening Resilience in North Carolina’s Communities and Community Resilience Has Many Faces…Part 1 referred to a set of measurements that have been developed for resilience and vulnerability for every county in the United States. These look at four dimensions: economic, social, infrastructure, and environmental. This blog looks at the infrastructure and environmental dimensions, and sets out to answer the questions: what do these mean and how can they be measured? How do the four measures come together to describe community resilience? Infrastructure Resilience and Vulnerability. The most obvious and immediate impacts of a disaster are often the damage done to roads and bridges, and the failure of facilities such as dams and levees. From an engineering standpoint, resilience is an expectation that physical infrastructure can be quickly restored to normal functioning based on acceptable standards of design, construction, and maintenance. There are also human and institutional factors that play into consideration of a more broadly-defined idea of infrastructure resilience and vulnerability. Thus, infrastructure resilience, in addition to adequacy of roadways, includes medical capacity, meaning ready access to a hospital with emergency facilities, availability of first responders, and the level of investment in the emergency response systems. It also includes convenient access to food as measured by proximity to a grocery store. Infrastructure vulnerability refers to those physical conditions and characteristics of the community which may put the population at a higher risk during and after a disaster. Four are particularly important. At-risk housing specifically a high percentage of housing units that are mobile homes or were built before 1960, and evacuation challenges where there are people living in group quarters or in homes with no vehicle available. The latter factor also includes a count of the number of bridges that either carry high levels of traffic or if damaged would involve long detours. Two other factors relate to physical infrastructure: high potential loss facilities estimating the population close to a dam or a nuclear facility, and water system quality where a system has been subject to health violations. In North Carolina, there are 36 counties that can be classified as having low infrastructure resilience and high infrastructure vulnerability. These are spread across rural North Carolina, along the Virginia border, the coastal plain, especially to the south, and parts of the mountain west. Environmental Resilience and Vulnerability. The fourth dimension focuses on the ability of the landscape to bounce back, absorb, or adapt to disasters, and on the range and severity of natural disaster risks faced by a community. Environmental resilience is a function of landscape diversity – the more diverse an area is in terms of climate, rock formations, land cover, and land-form, the more resilient it is. It is measured through an index derived from a complex international climate and land use database. Environmental vulnerability encompasses five main types of risk: the severity of storms, and the range of storm types that have impacted a community over the past 15 years, and the numbers of people at risk of flooding, earthquake, and drought. Based on national comparisons, 75 counties are classified as having high environmental resilience and low environmental vulnerability. Just five counties are classified as having low resilience and high vulnerability and these are clustered in the south of the coastal plain – Bladen, Brunswick, Columbus, Robeson, and Pender. Community Resilience and Vulnerability. When all four dimensions – social, economic, infrastructure, and environment – are combined, what does this tell us about the overall community resilience of North Carolina’s counties? Rather than attempt to create a composite of the four dimensions, the approach taken has been to count those counties that are in each of the four quadrant classifications and to highlight those counties that either have two or more dimensions with high resilience and low vulnerability, or with low resilience and high vulnerability. There are three North Carolina counties that are classified as high resilience and low vulnerability across all four dimensions: Cabarrus and Iredale in the Charlotte Metropolitan Area and Chatham in the Durham-Chapel Hill Metropolitan Area. There also a further 13 counties that are so classified on three dimensions to be found within or adjacent to the Metropolitan Areas of Asheville, Charlotte, Hickory, Winston-Salem, Durham-Chapel Hill, and Raleigh. At the other end of the The obvious next questions to be explored in future blogs are: Do these indexes and classifications have any meaning on the ground? What practical steps can governments and communities take to improve their resilience? What makes some counties highly resilient and others highly vulnerable? |

Published March 7, 2017 By Brian Dabson

The research project on community and regional resilience at the School of Government aims to help communities think differently about how they prepare for disasters and how they can become more resilient, providing data and information that can spark realistic conversations about a community’s future. This blog looks at some of the main elements that determine resilience and vulnerability in North Carolina’s counties. Previous blogs, Strengthening Resilience in North Carolina’s Communities and Community Resilience Has Many Faces…Part 1 referred to a set of measurements that have been developed for resilience and vulnerability for every county in the United States. These look at four dimensions: economic, social, infrastructure, and environmental. This blog looks at the infrastructure and environmental dimensions, and sets out to answer the questions: what do these mean and how can they be measured? How do the four measures come together to describe community resilience?

Infrastructure Resilience and Vulnerability. The most obvious and immediate impacts of a disaster are often the damage done to roads and bridges, and the failure of facilities such as dams and levees. From an engineering standpoint, resilience is an expectation that physical infrastructure can be quickly restored to normal functioning based on acceptable standards of design, construction, and maintenance. There are also human and institutional factors that play into consideration of a more broadly-defined idea of infrastructure resilience and vulnerability. Thus, infrastructure resilience, in addition to adequacy of roadways, includes medical capacity, meaning ready access to a hospital with emergency facilities, availability of first responders, and the level of investment in the emergency response systems. It also includes convenient access to food as measured by proximity to a grocery store.

Infrastructure vulnerability refers to those physical conditions and characteristics of the community which may put the population at a higher risk during and after a disaster. Four are particularly important. At-risk housing specifically a high percentage of housing units that are mobile homes or were built before 1960, and evacuation challenges where there are people living in group quarters or in homes with no vehicle available. The latter factor also includes a count of the number of bridges that either carry high levels of traffic or if damaged would involve long detours. Two other factors relate to physical infrastructure: high potential loss facilities estimating the population close to a dam or a nuclear facility, and water system quality where a system has been subject to health violations.

In North Carolina, there are 36 counties that can be classified as having low infrastructure resilience and high infrastructure vulnerability. These are spread across rural North Carolina, along the Virginia border, the coastal plain, especially to the south, and parts of the mountain west.

Environmental Resilience and Vulnerability. The fourth dimension focuses on the ability of the landscape to bounce back, absorb, or adapt to disasters, and on the range and severity of natural disaster risks faced by a community. Environmental resilience is a function of landscape diversity – the more diverse an area is in terms of climate, rock formations, land cover, and land-form, the more resilient it is. It is measured through an index derived from a complex international climate and land use database.

Environmental vulnerability encompasses five main types of risk: the severity of storms, and the range of storm types that have impacted a community over the past 15 years, and the numbers of people at risk of flooding, earthquake, and drought.

Based on national comparisons, 75 counties are classified as having high environmental resilience and low environmental vulnerability. Just five counties are classified as having low resilience and high vulnerability and these are clustered in the south of the coastal plain – Bladen, Brunswick, Columbus, Robeson, and Pender.

Community Resilience and Vulnerability. When all four dimensions – social, economic, infrastructure, and environment – are combined, what does this tell us about the overall community resilience of North Carolina’s counties?

Rather than attempt to create a composite of the four dimensions, the approach taken has been to count those counties that are in each of the four quadrant classifications and to highlight those counties that either have two or more dimensions with high resilience and low vulnerability, or with low resilience and high vulnerability. There are three North Carolina counties that are classified as high resilience and low vulnerability across all four dimensions: Cabarrus and Iredale in the Charlotte Metropolitan Area and Chatham in the Durham-Chapel Hill Metropolitan Area. There also a further 13 counties that are so classified on three dimensions to be found within or adjacent to the Metropolitan Areas of Asheville, Charlotte, Hickory, Winston-Salem, Durham-Chapel Hill, and Raleigh.

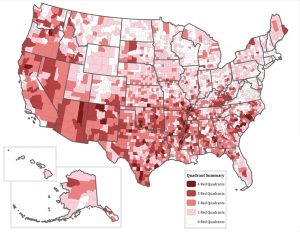

At the other end of the spectrum, there are three counties that are classified as having low resilience and high vulnerability across the four dimensions: Bladen, Columbus, and Robeson, a cluster of rural counties at the southern end of the inner coastal plain. There are another 12 counties that are similarly classified on three dimensions. Nine of these are on the inner coastal plain, with two in the southern Piedmont, and one in the far west. The map shows those counties nationwide with low resilience and high vulnerability across one or more dimensions, with the darkest red across all four.

spectrum, there are three counties that are classified as having low resilience and high vulnerability across the four dimensions: Bladen, Columbus, and Robeson, a cluster of rural counties at the southern end of the inner coastal plain. There are another 12 counties that are similarly classified on three dimensions. Nine of these are on the inner coastal plain, with two in the southern Piedmont, and one in the far west. The map shows those counties nationwide with low resilience and high vulnerability across one or more dimensions, with the darkest red across all four.

The obvious next questions to be explored in future blogs are: Do these indexes and classifications have any meaning on the ground? What practical steps can governments and communities take to improve their resilience? What makes some counties highly resilient and others highly vulnerable?

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.