|

|

Student Corner: 4% LIHTC Use in North Carolina’s Triangle RegionBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished July 25, 2017

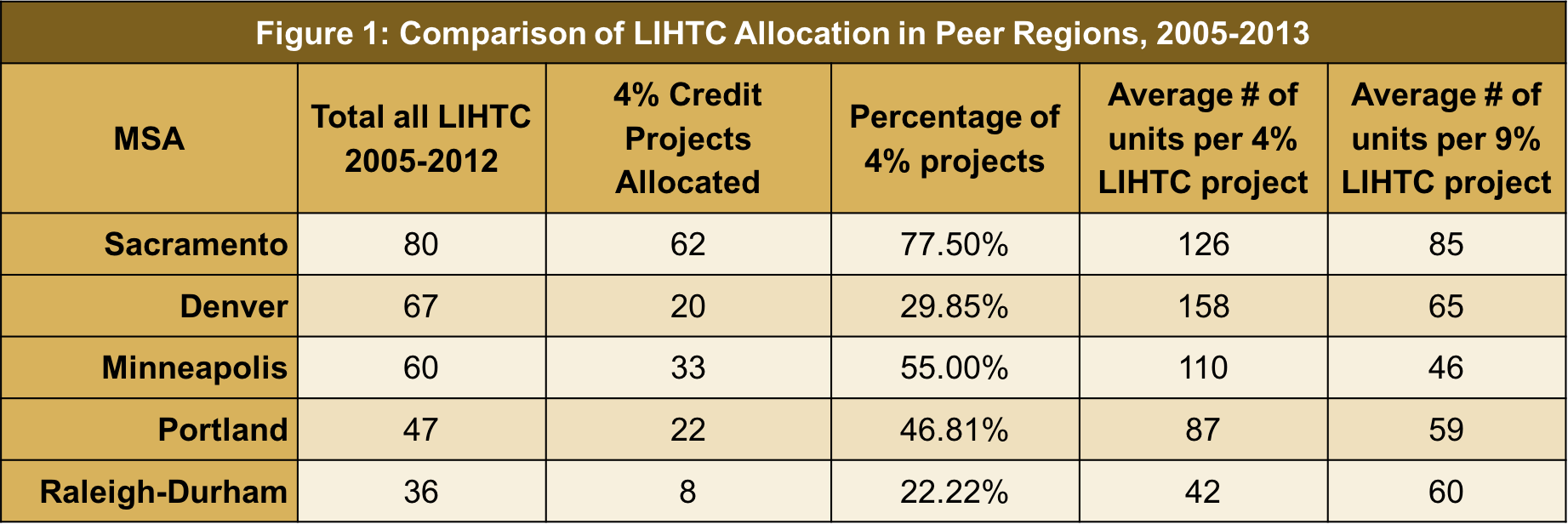

Development of low-income housing in the United States continues to be a challenge for local governments, affordable housing developers, and policy advocates. Institutional, market, and financing obstacles are all barriers to increasing the supply of affordable housing. Since the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) have helped finance 2.6 million low-cost housing units. The LIHTC program seeks to address the financial barriers by incentivizing private investment in the affordable housing market. Despite lower vacancy and debt service common in affordable housing deals, lower rents often result in a project that are not feasible for private developers, resulting in a funding gap. Developers of low-income housing units, therefore, must gain access to various sources of gap financing such as low-income housing tax credits. The LIHTC program offers two tax credits types: the 4% and the 9%. The 9% credits, limited by federal law and distributed on a per capita basis to states, amount to a larger benefit for the tax credit developer, usually accounting for 70% of total project costs. However, use of the 9% credits prohibit the developer from using additional federal subsidy programs and a competitive application process allocates limited credits to a few successful bids. The 4% credits, on the other hand, leave open the opportunity for developers to take advantage of additional federal subsidies and are accessible through a noncompetitive application, but cover a smaller portion of the total project costs (usually nearing 30%). The additional funding sources eligible for 4% LIHTC projects help to close this larger funding gap. Bond Deals and Other Gap Funding Integral to the use of 4% credits, developers make use of bonds, municipally provided loans, and additional grant funding. The bonds most commonly available to developers are private activity bonds issued by local governments. These bonds are critical to obtaining and using the 4% LIHTC tool. Only projects with 50% or more of the project costs financed through tax exempt bonds are automatically awarded the 4% LIHTC credit. This, known as the 50% test, makes local government bonds and their interest rates critical to the success of 4% LIHTC projects. Additional funding available to close the gap on 4% tax credit projects come in the form of grants from programs like the federal HOME Investment Partnerships (HOME) and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) programs. State and local jurisdictions receive these allocations from the federal government and determine how to allocate them to specific projects. 4% LIHTC Use in North Carolina’s Research Triangle The Research Triangle of North Carolina is a growing region of many local municipalities. As incomes have risen and development pressures rise, however, the tools for affordable housing are increasingly important. Compared to other growing, dynamic peer regions across the country however, use of the 4% LIHTC has lagged in Raleigh-Durham since 2005. Since 2005 in North Carolina, 267 LIHTC projects have been allocated credits, only 46 of which have used 4% credits exclusively. Figure 1 shows the allocation and use of credits in the Triangle region and in peer regions since 2005 to 2013. Compared to peer regions, the Triangle’s LIHTC use has been characterized by:

This data begins to show how the Triangle region has been unsuccessful in leveraging LIHTC opportunities relative to its peer regions. While the policies and circumstances that led to this difference require further exploration, interviews with area banks and affordable housing developers point to two primary contributing factors:

As local governments in the Triangle and around North Carolina grapple with how to meet the needs of residents unable to pay market rate for housing, they should be aware of the 4% LIHTC program to give affordable housing developers an noncompetitive route for financing that can leverage existing public-private partnerships. Changes in market forces may already be dictating further interest in the 4% credit, and bonds raised for affordable housing are a real possibility in many municipalities, meaning that past trends may not be the future for LIHTC use in North Carolina. Peter Gorman is a recent graduate of the Master’s program in the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning specializing in Economic Development and a former Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. |

Published July 25, 2017 By CED Program Interns & Students

A Brief Introduction to the 4% Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

A Brief Introduction to the 4% Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

Development of low-income housing in the United States continues to be a challenge for local governments, affordable housing developers, and policy advocates. Institutional, market, and financing obstacles are all barriers to increasing the supply of affordable housing. Since the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) have helped finance 2.6 million low-cost housing units. The LIHTC program seeks to address the financial barriers by incentivizing private investment in the affordable housing market. Despite lower vacancy and debt service common in affordable housing deals, lower rents often result in a project that are not feasible for private developers, resulting in a funding gap. Developers of low-income housing units, therefore, must gain access to various sources of gap financing such as low-income housing tax credits.

The LIHTC program offers two tax credits types: the 4% and the 9%. The 9% credits, limited by federal law and distributed on a per capita basis to states, amount to a larger benefit for the tax credit developer, usually accounting for 70% of total project costs. However, use of the 9% credits prohibit the developer from using additional federal subsidy programs and a competitive application process allocates limited credits to a few successful bids. The 4% credits, on the other hand, leave open the opportunity for developers to take advantage of additional federal subsidies and are accessible through a noncompetitive application, but cover a smaller portion of the total project costs (usually nearing 30%). The additional funding sources eligible for 4% LIHTC projects help to close this larger funding gap.

Bond Deals and Other Gap Funding

Integral to the use of 4% credits, developers make use of bonds, municipally provided loans, and additional grant funding. The bonds most commonly available to developers are private activity bonds issued by local governments. These bonds are critical to obtaining and using the 4% LIHTC tool. Only projects with 50% or more of the project costs financed through tax exempt bonds are automatically awarded the 4% LIHTC credit. This, known as the 50% test, makes local government bonds and their interest rates critical to the success of 4% LIHTC projects.

Additional funding available to close the gap on 4% tax credit projects come in the form of grants from programs like the federal HOME Investment Partnerships (HOME) and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) programs. State and local jurisdictions receive these allocations from the federal government and determine how to allocate them to specific projects.

4% LIHTC Use in North Carolina’s Research Triangle

The Research Triangle of North Carolina is a growing region of many local municipalities. As incomes have risen and development pressures rise, however, the tools for affordable housing are increasingly important. Compared to other growing, dynamic peer regions across the country however, use of the 4% LIHTC has lagged in Raleigh-Durham since 2005. Since 2005 in North Carolina, 267 LIHTC projects have been allocated credits, only 46 of which have used 4% credits exclusively. Figure 1 shows the allocation and use of credits in the Triangle region and in peer regions since 2005 to 2013. Compared to peer regions, the Triangle’s LIHTC use has been characterized by:

- Low 4% allocation rates: The triangle region generated 4% LIHTC projects totally only 22% of the total LIHTC projects, while peer regions 4% projects average 52% of the total.

- Fewer units in 4% projects relative to 9% projects: The Triangle region is unique amongst its peers in its 4% projects are smaller than its 9% projects. Data points to 4% projects being uniquely small, rather than larger than normal 9% projects.

This data begins to show how the Triangle region has been unsuccessful in leveraging LIHTC opportunities relative to its peer regions. While the policies and circumstances that led to this difference require further exploration, interviews with area banks and affordable housing developers point to two primary contributing factors:

- Limited Gap Financing: The financing gaps inherent in 4% LIHTC projects have few options in public money, from both legal restrictions, and policy choices. With the current available financing set aside for affordable housing, projects like the 198 unit Bluffs at Walnut Creek would drain Raleigh’s entire reserve of affordable housing funds for two years, and Durham’s for two years.

- Limited moderately affordable need: In the Triangle region, average rent as a portion of average income has only recently increased above the 30% affordability threshold associated with 4% LIHTC projects, and in the past, housing affordability was typically quite high. With these low rents, developers are particularly cognizant that the additional costs of LIHTC processing push the chargeable rents close to the 30% AMI limit. In the low-rent, high-income Triangle region those chargeable rents approach or exceed market price, meaning that potential tenants would gravitate to market priced units to avoid the hassle and uncertainty of income, asset, and personal qualifications they must meet in the LIHTC rental application.

As local governments in the Triangle and around North Carolina grapple with how to meet the needs of residents unable to pay market rate for housing, they should be aware of the 4% LIHTC program to give affordable housing developers an noncompetitive route for financing that can leverage existing public-private partnerships. Changes in market forces may already be dictating further interest in the 4% credit, and bonds raised for affordable housing are a real possibility in many municipalities, meaning that past trends may not be the future for LIHTC use in North Carolina.

Peter Gorman is a recent graduate of the Master’s program in the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning specializing in Economic Development and a former Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.