|

|

Local Government Financial Resilience and Preparation Before a Natural DisasterBy CED Guest AuthorPublished November 28, 2017This year’s U.S. Atlantic hurricane season is officially the most expensive ever, amounting to $202.6 billion in damages across the Atlantic basin. This record-breaking hurricane season brought some of the most catastrophic storms in recent memory. As Hurricane Katrina reshaped New Orleans in 2005, the destruction induced by Harvey, Irma, and Maria will have lasting consequences for cities and towns in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. The devastation is likely to be even more long-lasting for many of the hardest hit small islands across the Caribbean. And hurricanes are not the only natural disasters with a hefty price tag; drought, freezing temperatures, severe storms, wildfires, and winter storms cause billions of dollars in damages every year. As a result of rapid urbanization, climate change, and increases in population and material wealth continue to mount, municipalities are becoming extremely vulnerable to natural disasters, making it necessary for local governments to become more resilient to catastrophes. Natural disaster resiliency often focuses on the built environment and hazard mitigation, but what about weathering the storm from a financial perspective? The following tips can help a local government be financially resilient in the face of a natural disaster: Identify natural disasters with prospective financial implications for your areaLocal governments often have to plan financially for major events that will impact their community, such as a manufacturing plant closing and resulting in a loss of revenue. Just as local governments plan for this sort of major events, it is also possible to plan for the financial impacts of natural disasters. Many local governments in the Great Lakes region, for example, budget annually for snow removal. With winter weather approaching, snowstorms are a type of natural disaster that local governments in areas cooler areas can plan for because they are very frequent, predictable events. In most cases, a community or region will not be able to plan financially for low‐frequency, highly unpredictable natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes in North Carolina) but financial planning can be undertaken for many other disasters. Which types of disasters should you consider planning for financially? These could include:

There are many resources available in identifying natural disasters that are more likely in your area. For example, Colorado State University has estimated the probabilities of a small tropical storm as well as a major hurricane passing through coastal counties in the Gulf Coast and Atlantic regions. Another useful source of information about natural disaster risks can be local emergency managers in your area, as they may have already assessed these risks for local hazard mitigation plan required by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). State hazard mitigation plans may also contain useful information; North Carolina has an enhanced hazard mitigation plan available for public download. Local government officials can also turn to help from the regional offices of federal agencies such as FEMA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for useful information. Both FEMA and NOAA offer free data tools that can help local governments assess economic risks, such as HAZUS, Digital Coast, and the National Centers for Environmental Information, formerly the National Climactic Data Center. For more resources specific to North Carolina, see the School of Government’s NC Emergency Management site and Ready NC. Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Set a timelineAfter deciding which natural disasters have the most probability of reaching your community, local governments need to also identify the time horizon they will use for financial planning. This part of financial resiliency for natural disasters has no single optimal time horizon. One strategy local governments can use to choose a time horizon is to build a time horizon around the frequency of the disaster’s occurrence in the specific region. If a local government knows the probability of a Category 3 hurricane hitting its area is once every 15 years, then 15 years could be an ideal time horizon to consider for financial planning for that type of disaster event. Know what’s availableit is important for local governments to be knowledgeable about funding sources and how to get hold of money in a crisis–and it is better to know that in advance, rather than having to figure it out after disaster strikes. Knowing what sort of funds are allowed to be used for disaster planning or relief is also important. Some local governments collect taxes and receive revenues from fees that are unrestricted, and these funds can be used to pay for any classification of local government expenses, including emergency expenses after natural disasters. Some government revenues are restricted and cannot be used for disaster relief. Insurance is another important aspect of funding the costs of a natural disaster. In the case of flood disasters, for example, being up to date on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is a good place to start to be financially resilient to floods. In addition, within the NFIP there are parts of the program that encourage local governments to take certain mitigation measures, and if they meet certain requirements, they get more favorable premiums for flood insurance in that community. Set up a rainy day fundA local government’s rainy day fund, if they have one, can be used for just about anything. Many states keep rainy day funds that are governed by law–the law sets the target fund balance and outlines when to use and replenish that balance. Local governments typically do not set up such formal structures. Rather, many localities look to unreserved fund balances or budget surpluses as a rainy day fund, but one without the constraints of a formal fund policy. While these informal practices are not as transparent as most state policies, they do allow for more flexibility in times of a crisis, such as a natural disaster. Other resourcesThe UNC School of Government offers resources for natural disaster emergency planning. Check out the School’s NC Emergency Management site and blog posts, and sign up to stay connected with a topical listserv here. Other resources to help financially weather natural disasters include:

Liz Harvell is Outreach Coordinator at the Environmental Finance Center at the UNC School of Government.

|

Published November 28, 2017 By CED Guest Author

This year’s U.S. Atlantic hurricane season is officially the most expensive ever, amounting to $202.6 billion in damages across the Atlantic basin. This record-breaking hurricane season brought some of the most catastrophic storms in recent memory. As Hurricane Katrina reshaped New Orleans in 2005, the destruction induced by Harvey, Irma, and Maria will have lasting consequences for cities and towns in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. The devastation is likely to be even more long-lasting for many of the hardest hit small islands across the Caribbean. And hurricanes are not the only natural disasters with a hefty price tag; drought, freezing temperatures, severe storms, wildfires, and winter storms cause billions of dollars in damages every year.

As a result of rapid urbanization, climate change, and increases in population and material wealth continue to mount, municipalities are becoming extremely vulnerable to natural disasters, making it necessary for local governments to become more resilient to catastrophes. Natural disaster resiliency often focuses on the built environment and hazard mitigation, but what about weathering the storm from a financial perspective? The following tips can help a local government be financially resilient in the face of a natural disaster:

Identify natural disasters with prospective financial implications for your area

Local governments often have to plan financially for major events that will impact their community, such as a manufacturing plant closing and resulting in a loss of revenue. Just as local governments plan for this sort of major events, it is also possible to plan for the financial impacts of natural disasters. Many local governments in the Great Lakes region, for example, budget annually for snow removal. With winter weather approaching, snowstorms are a type of natural disaster that local governments in areas cooler areas can plan for because they are very frequent, predictable events.

In most cases, a community or region will not be able to plan financially for low‐frequency, highly unpredictable natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes in North Carolina) but financial planning can be undertaken for many other disasters. Which types of disasters should you consider planning for financially? These could include:

- Hurricanes

- Tornadoes

- Floods

- Droughts

- Wildfires

- Snow and ice storms

- Other natural disasters specific to your region

There are many resources available in identifying natural disasters that are more likely in your area. For example, Colorado State University has estimated the probabilities of a small tropical storm as well as a major hurricane passing through coastal counties in the Gulf Coast and Atlantic regions.

Another useful source of information about natural disaster risks can be local emergency managers in your area, as they may have already assessed these risks for local hazard mitigation plan required by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). State hazard mitigation plans may also contain useful information; North Carolina has an enhanced hazard mitigation plan available for public download.

Local government officials can also turn to help from the regional offices of federal agencies such as FEMA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for useful information. Both FEMA and NOAA offer free data tools that can help local governments assess economic risks, such as HAZUS, Digital Coast, and the National Centers for Environmental Information, formerly the National Climactic Data Center. For more resources specific to North Carolina, see the School of Government’s NC Emergency Management site and Ready NC.

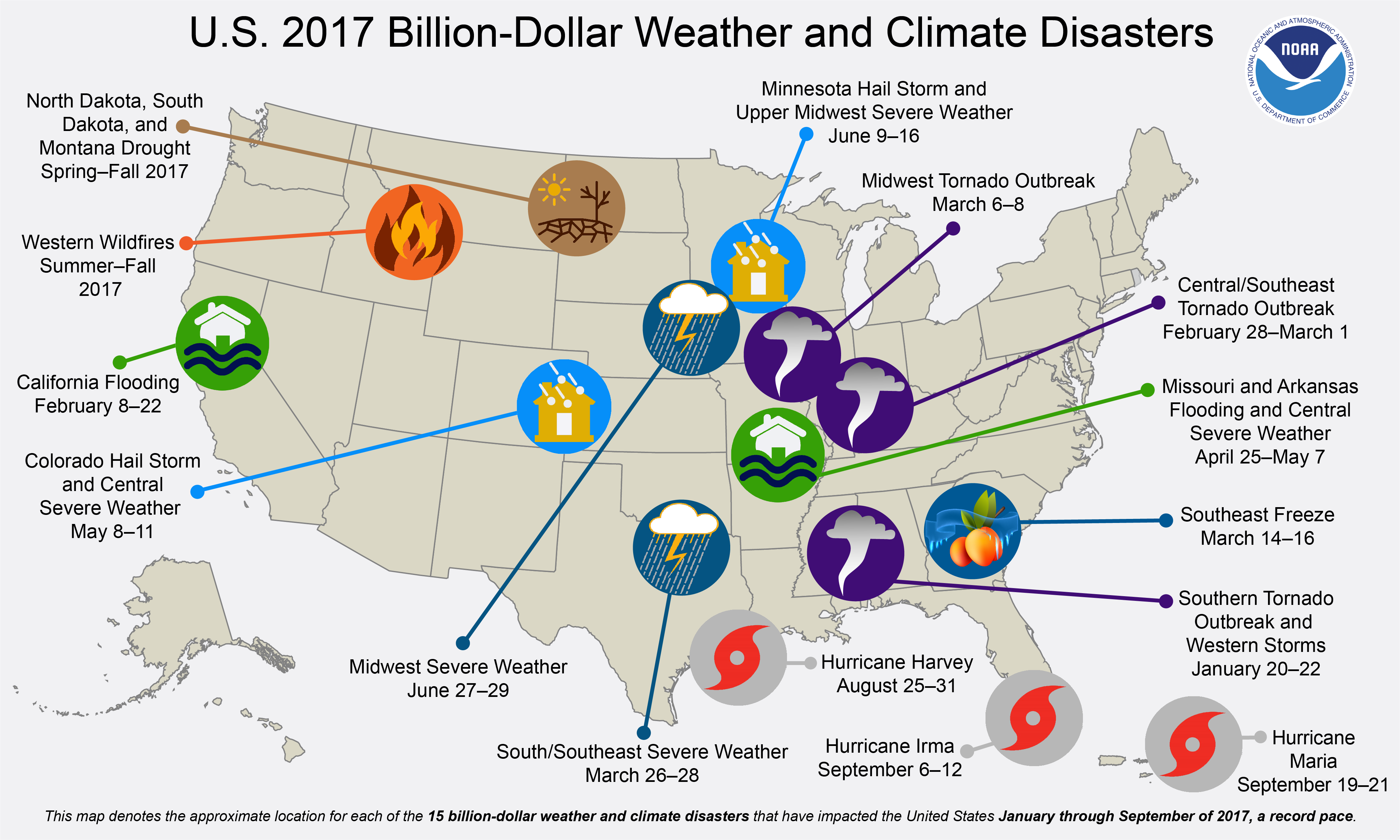

Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Set a timeline

After deciding which natural disasters have the most probability of reaching your community, local governments need to also identify the time horizon they will use for financial planning. This part of financial resiliency for natural disasters has no single optimal time horizon. One strategy local governments can use to choose a time horizon is to build a time horizon around the frequency of the disaster’s occurrence in the specific region. If a local government knows the probability of a Category 3 hurricane hitting its area is once every 15 years, then 15 years could be an ideal time horizon to consider for financial planning for that type of disaster event.

Know what’s available

it is important for local governments to be knowledgeable about funding sources and how to get hold of money in a crisis–and it is better to know that in advance, rather than having to figure it out after disaster strikes. Knowing what sort of funds are allowed to be used for disaster planning or relief is also important. Some local governments collect taxes and receive revenues from fees that are unrestricted, and these funds can be used to pay for any classification of local government expenses, including emergency expenses after natural disasters. Some government revenues are restricted and cannot be used for disaster relief.

Insurance is another important aspect of funding the costs of a natural disaster. In the case of flood disasters, for example, being up to date on the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is a good place to start to be financially resilient to floods. In addition, within the NFIP there are parts of the program that encourage local governments to take certain mitigation measures, and if they meet certain requirements, they get more favorable premiums for flood insurance in that community.

Set up a rainy day fund

A local government’s rainy day fund, if they have one, can be used for just about anything. Many states keep rainy day funds that are governed by law–the law sets the target fund balance and outlines when to use and replenish that balance. Local governments typically do not set up such formal structures. Rather, many localities look to unreserved fund balances or budget surpluses as a rainy day fund, but one without the constraints of a formal fund policy. While these informal practices are not as transparent as most state policies, they do allow for more flexibility in times of a crisis, such as a natural disaster.

Other resources

The UNC School of Government offers resources for natural disaster emergency planning. Check out the School’s NC Emergency Management site and blog posts, and sign up to stay connected with a topical listserv here. Other resources to help financially weather natural disasters include:

- Disaster Recovery: A Local Government Responsibility

- Financial Planning for Natural Disasters: A Workbook for Local Governments and Regions

- Pre-Disaster Recovery Planning Guide for Local Governments

- Disaster Recovery Financial Assistance

Liz Harvell is Outreach Coordinator at the Environmental Finance Center at the UNC School of Government.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.