|

|

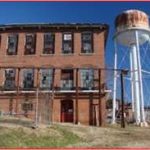

Maintenance of vacant or neglected commercial buildings: options for NC local governmentsBy Tyler MulliganPublished March 20, 2018U The downtown buildings in the Town of Old Well have “good bones.” The structures lining the four downtown blocks of Main Street are solid brick and reflect their historic character, harkening back to a time when downtown was thriving with retail on the ground floor and residential units on the second floor. The very center of downtown is in fairly good shape, and some committed merchants have established a pocket of commercial activity there. However, even that central area is pocked with a handful of underutilized and neglected retail buildings. The downtown blocks immediately outside of the center, where vacant buildings outnumber those with active uses, are not inviting to pedestrians. Residents and downtown merchants have complained to Town officials about the privately-owned vacant buildings within and surrounding the center of downtown. Some of the vacant structures are in fair condition but are used for storage; peering through the wide display windows reveals piles of boxes, dusty floors, litter, or worse. Some display windows are papered over to conceal the interior. While a handful of vacant buildings appear to be in good condition, others look visibly worse than those with active uses. Can Town officials enact any regulations to govern the appearance and general maintenance of these commercial buildings? Yes, they can. In fact, there are a number of options available by statute to Town officials. The options provided below are organized according to the condition of the structure, ranging from “green” (good) condition to “yellow” or “red” (worse) condition. The “green-yellow-red” framework and corresponding statutory authority is summarized in a one page downloadable handout: Repair of Nonresidential Buildings. This framework is based on a parallel framework devised for dwellings (not commercial buildings) in the book, Housing Codes for Repair and Maintenance: Using the General Police Power and Minimum Housing Statutes to Prevent Dwelling Deterioration. The one page downloadable handout should be read as a supplement to the material in the Housing Codes book. A brief overview of building conditions (green-yellow-red) and legal authority for regulating the repair and maintenance of nonresidential buildings is provided below. Green condition – vacant commercial buildings in good repair

Courts will uphold police power regulations so long as they are reasonable.[2] The Supreme Court of North Carolina, in State v. Jones, even upheld police power regulations for aesthetic considerations alone, provided the “gain to the public” outweighs the burden on the property owner.[3] The assessment of the “gain to the public” may include “corollary benefits to the general community” such as “protection of property values,” “preservation of the character and integrity of the community,” and “promotion of the comfort, happiness, and emotional stability of area residents.” For detailed analysis of the general police power and local ordinances regulating vacant properties, see Chapter 2 of the Housing Codes book. The book’s analysis of vacant residential buildings is equally applicable to vacant nonresidential buildings. Reasonable regulations may include a requirement for vacant buildings to be registered with the local government so that periodic inspections may be performed. Inspections would verify that buildings remain secure and contain no hazardous conditions related to fire, flooding, or criminal activity. The General Assembly has imposed some restrictions on inspections of residential units, but no restrictions are imposed for periodic inspections of nonresidential structures.[4] Yellow condition – obviously vacant or visible maintenance deficiencies

Although no North Carolina statutes grant specific authority for regulation of “yellow” buildings, a local government may employ its general police power and ordinance making authority to design and enforce reasonable regulations. This authority is the same as described above for “green” buildings. Some North Carolina towns have adopted ordinances requiring owners to eliminate any “evidence of vacancy” in commercial buildings, such as empty or papered window fronts, visibly vacant spaces, inattention to exterior building appearance, and other deficiencies that impair the downtown “character and integrity.” An example of one such ordinance is available here. Local governments should be aware that enforcement of police power ordinances (G.S. 153A-121 & 160A-174) requires staff time and resources. An owner that refuses to comply with an order to address maintenance deficiencies can be fined and the local government may seek a court order to abate the condition without the owner’s consent (G.S. 153A-123(e) & 160A-175(e)). The costs of abatement or repair incurred by the local government become a low priority lien on the property. The low priority of the lien means the local government may not be able to recover those costs (compare to repair actions described below for “red” buildings which result in high priority liens collected like taxes). My faculty colleague Trey Allen discusses the enforcement options in more detail in a blog post on ordinance enforcement basics. Red condition – building is dangerous or hazardous but can be repaired at reasonable cost

In order to exercise a particular statutory power described above, a local government must first adopt a local ordinance containing the necessary procedures for exercise of the statutory authority. The statutory powers described above are not mutually exclusive. A local government may adopt and employ one or more of the statutory powers to any particular “red” building, provided the statute is appropriate for the specific circumstances and the relevant statutory procedures are followed. The powers granted by G.S. Chapter 160D above may also apply to a municipality’s extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ), provided the municipality is exercising those same Chapter 160D powers “within its corporate limits.” G.S. 160D-202. Black and blue condition – building is in need of demolition or removal

Take a strategic approach to code enforcement and revitalization Strategic code enforcement is the first step in revitalization. To see detailed recommendations regarding strategic code enforcement for housing, provided to a North Carolina city by a team from the Center for Community Progress and the School of Government, see the report, Strategic Code Enforcement for Vacancy & Abandonment in High Point NC (CCP Report 2016). Code enforcement alone may not be sufficient to revitalize a distressed area. To accomplish revitalization, it may be necessary to employ a land banking approach. Land banking involves acquiring key properties, holding and improving properties, and conveying properties to private developers with conditions in pursuit of a revitalization strategy. The land banking approach is described in my blog post, How a North Carolina Local Government Can Operate a Land Bank for Redevelopment. Some local governments have established redevelopment areas to aid in the revitalization process. Urban redevelopment areas are described in my blog post, Using a Redevelopment Area to Attract Private Investment. A program at the School of Government, the Development Finance Initiative (DFI), was created to assist local governments with attracting private investment to accomplish their community and economic development goals. Many DFI projects are undertaken with the goal of revitalizing a distressed area with vacant or underutilized structures. Examples of DFI projects can be reviewed here.

[1] HUD – Evidence Matters, Vacant and Abandoned Properties: Turning Liabilities Into Assets (Winter 2014); Accordino & Johnson, Addressing the Vacant and Abandoned Property Problem, Journal of Urban Affairs 22:3, 302–3 (2002)). [2] A-S-P Associates v. City of Raleigh, 298 N.C. 207 (1979). [3] 305 N.C. 520 (1982). The reasonableness of aesthetic regulations is determined on a case-by-case basis by examining “whether the aesthetic purpose to which the regulation is reasonably related outweighs the burdens imposed on the private property owner by the regulation.” Id. at 530-01. [4] Mulligan, Residential Rental Property Inspections, Permits, and Registration: Changes for 2017, Community and Economic Development Bulletin #9, available for download here. Question 18 in the bulletin explains that recent changes to periodic inspections statutes apply only to residential units, not nonresidential structures. |

Published March 20, 2018 By Tyler Mulligan

U PDATE 2021: Some statutory provisions referenced in the original post were relocated to new Chapter 160D of the North Carolina General Statutes, effective January 1, 2021. This post has been updated with the new statutory references.

PDATE 2021: Some statutory provisions referenced in the original post were relocated to new Chapter 160D of the North Carolina General Statutes, effective January 1, 2021. This post has been updated with the new statutory references.

The downtown buildings in the Town of Old Well have “good bones.” The structures lining the four downtown blocks of Main Street are solid brick and reflect their historic character, harkening back to a time when downtown was thriving with retail on the ground floor and residential units on the second floor. The very center of downtown is in fairly good shape, and some committed merchants have established a pocket of commercial activity there. However, even that central area is pocked with a handful of underutilized and neglected retail buildings. The downtown blocks immediately outside of the center, where vacant buildings outnumber those with active uses, are not inviting to pedestrians.

Residents and downtown merchants have complained to Town officials about the privately-owned vacant buildings within and surrounding the center of downtown. Some of the vacant structures are in fair condition but are used for storage; peering through the wide display windows reveals piles of boxes, dusty floors, litter, or worse. Some display windows are papered over to conceal the interior. While a handful of vacant buildings appear to be in good condition, others look visibly worse than those with active uses. Can Town officials enact any regulations to govern the appearance and general maintenance of these commercial buildings? Yes, they can.

In fact, there are a number of options available by statute to Town officials. The options provided below are organized according to the condition of the structure, ranging from “green” (good) condition to “yellow” or “red” (worse) condition. The “green-yellow-red” framework and corresponding statutory authority is summarized in a one page downloadable handout: Repair of Nonresidential Buildings. This framework is based on a parallel framework devised for dwellings (not commercial buildings) in the book, Housing Codes for Repair and Maintenance: Using the General Police Power and Minimum Housing Statutes to Prevent Dwelling Deterioration. The one page downloadable handout should be read as a supplement to the material in the Housing Codes book.

A brief overview of building conditions (green-yellow-red) and legal authority for regulating the repair and maintenance of nonresidential buildings is provided below.

Green condition – vacant commercial buildings in good repair

“Green” buildings are in good condition and not in any obvious need of repair. When such buildings are vacant for long periods, however, it has been shown that their unmonitored state poses a risk of accidental fire or flooding, declining property values, and arson or other criminal activity.[1] In North Carolina, no statute grants specific authority to regulate “green” condition structures that are vacant. However, North Carolina local governments may employ their general ordinance making authority under the police power to design and enforce their own regulations of anything that is “detrimental to the health, safety, or welfare” of residents and the “peace and dignity” of the jurisdiction (G.S. 153A-121 & 160A-174). Vacant buildings are demonstrably detrimental to the community in the literature and therefore the exercise of the police power is appropriate.

“Green” buildings are in good condition and not in any obvious need of repair. When such buildings are vacant for long periods, however, it has been shown that their unmonitored state poses a risk of accidental fire or flooding, declining property values, and arson or other criminal activity.[1] In North Carolina, no statute grants specific authority to regulate “green” condition structures that are vacant. However, North Carolina local governments may employ their general ordinance making authority under the police power to design and enforce their own regulations of anything that is “detrimental to the health, safety, or welfare” of residents and the “peace and dignity” of the jurisdiction (G.S. 153A-121 & 160A-174). Vacant buildings are demonstrably detrimental to the community in the literature and therefore the exercise of the police power is appropriate.

Courts will uphold police power regulations so long as they are reasonable.[2] The Supreme Court of North Carolina, in State v. Jones, even upheld police power regulations for aesthetic considerations alone, provided the “gain to the public” outweighs the burden on the property owner.[3] The assessment of the “gain to the public” may include “corollary benefits to the general community” such as “protection of property values,” “preservation of the character and integrity of the community,” and “promotion of the comfort, happiness, and emotional stability of area residents.” For detailed analysis of the general police power and local ordinances regulating vacant properties, see Chapter 2 of the Housing Codes book. The book’s analysis of vacant residential buildings is equally applicable to vacant nonresidential buildings.

Reasonable regulations may include a requirement for vacant buildings to be registered with the local government so that periodic inspections may be performed. Inspections would verify that buildings remain secure and contain no hazardous conditions related to fire, flooding, or criminal activity. The General Assembly has imposed some restrictions on inspections of residential units, but no restrictions are imposed for periodic inspections of nonresidential structures.[4]

Yellow condition – obviously vacant or visible maintenance deficiencies

“Yellow” buildings are obviously vacant or, if not vacant, show signs of minor disrepair (not yet dangerous or hazardous). Whether vacant or not, buildings in “yellow” condition jeopardize “benefits to the general public” (to use the North Carolina Supreme Court’s words) such as “property values” “and the “character and integrity of the community.” There is a clear basis for the exercise of the police power in order to encourage owners of “yellow” buildings to correct visible maintenance deficiencies and to remove evidence of vacancy.

“Yellow” buildings are obviously vacant or, if not vacant, show signs of minor disrepair (not yet dangerous or hazardous). Whether vacant or not, buildings in “yellow” condition jeopardize “benefits to the general public” (to use the North Carolina Supreme Court’s words) such as “property values” “and the “character and integrity of the community.” There is a clear basis for the exercise of the police power in order to encourage owners of “yellow” buildings to correct visible maintenance deficiencies and to remove evidence of vacancy.

Although no North Carolina statutes grant specific authority for regulation of “yellow” buildings, a local government may employ its general police power and ordinance making authority to design and enforce reasonable regulations. This authority is the same as described above for “green” buildings. Some North Carolina towns have adopted ordinances requiring owners to eliminate any “evidence of vacancy” in commercial buildings, such as empty or papered window fronts, visibly vacant spaces, inattention to exterior building appearance, and other deficiencies that impair the downtown “character and integrity.” An example of one such ordinance is available here.

Local governments should be aware that enforcement of police power ordinances (G.S. 153A-121 & 160A-174) requires staff time and resources. An owner that refuses to comply with an order to address maintenance deficiencies can be fined and the local government may seek a court order to abate the condition without the owner’s consent (G.S. 153A-123(e) & 160A-175(e)). The costs of abatement or repair incurred by the local government become a low priority lien on the property. The low priority of the lien means the local government may not be able to recover those costs (compare to repair actions described below for “red” buildings which result in high priority liens collected like taxes). My faculty colleague Trey Allen discusses the enforcement options in more detail in a blog post on ordinance enforcement basics.

Red condition – building is dangerous or hazardous but can be repaired at reasonable cost

A building in “red” condition is one that is dangerous or hazardous but still can be repaired at a reasonable cost. There are several statutes specifically addressing “red” buildings, and these statutes represent a significant enhancement of authority as compared to the general ordinance making power described above.

A building in “red” condition is one that is dangerous or hazardous but still can be repaired at a reasonable cost. There are several statutes specifically addressing “red” buildings, and these statutes represent a significant enhancement of authority as compared to the general ordinance making power described above.

- Nonresidential Building Maintenance Codes (G.S. 160D-1129). Local governments may use G.S. 160D-1129 for mandatory repair of commercial buildings, but only for a building that has “not been properly maintained so that the safety or health of its occupants or members of the general public is jeopardized.” Enforcement involves relatively simpler administrative procedures, as opposed to a court order, and the cost of local government effectuation becomes a high priority lien on the property collected like property taxes. One municipality’s non-residential building code, which authorizes mandatory repair orders, is available here.

- Compulsory repair in Urban Redevelopment Areas (G.S. 160A-503(19)). Local governments may enact programs of compulsory repair within designated urban redevelopment areas. The process for identifying blight and designating a redevelopment area is described in my blog post, Using a Redevelopment Area to Attract Private Investment. One municipality’s program is available here.

- Repair of abandoned structures (G.S. 160D-1201(b)). Local governments may follow minimum housing code procedures to order repair of any structure—including nonresidential structures—deemed to be abandoned and a health or safety hazard. See the Housing Codes book, Chapter 3, for more detail on minimum housing code procedures.

- Prevent demolition by neglect of historic landmarks (G.S. 160D-949/950). Maintenance requirements can be imposed for buildings designated as historic landmarks through a demolition by neglect ordinance, as discussed in a blog post on demolition by neglect written by my faculty colleague Adam Lovelady.

In order to exercise a particular statutory power described above, a local government must first adopt a local ordinance containing the necessary procedures for exercise of the statutory authority. The statutory powers described above are not mutually exclusive. A local government may adopt and employ one or more of the statutory powers to any particular “red” building, provided the statute is appropriate for the specific circumstances and the relevant statutory procedures are followed. The powers granted by G.S. Chapter 160D above may also apply to a municipality’s extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ), provided the municipality is exercising those same Chapter 160D powers “within its corporate limits.” G.S. 160D-202.

Black and blue condition – building is in need of demolition or removal

Buildings in “black and blue” condition are in need of demolition or removal—they are, in most cases, beyond repair. For these buildings, local governments often employ unsafe building condemnation (G.S. 160D-1119 et seq.). The effective provisions of these statutes are generally available to local governments without requiring a local ordinance to be enacted in advance. Retired faculty member Rich Ducker discusses building condemnation and demolition procedures in a blog post on nuisance abatement. Trey Allen discusses summary abatement or demolition of buildings posing an imminent danger to the public in his blog post on ordinance enforcement basics.

Buildings in “black and blue” condition are in need of demolition or removal—they are, in most cases, beyond repair. For these buildings, local governments often employ unsafe building condemnation (G.S. 160D-1119 et seq.). The effective provisions of these statutes are generally available to local governments without requiring a local ordinance to be enacted in advance. Retired faculty member Rich Ducker discusses building condemnation and demolition procedures in a blog post on nuisance abatement. Trey Allen discusses summary abatement or demolition of buildings posing an imminent danger to the public in his blog post on ordinance enforcement basics.

Take a strategic approach to code enforcement and revitalization

Strategic code enforcement is the first step in revitalization. To see detailed recommendations regarding strategic code enforcement for housing, provided to a North Carolina city by a team from the Center for Community Progress and the School of Government, see the report, Strategic Code Enforcement for Vacancy & Abandonment in High Point NC (CCP Report 2016).

Code enforcement alone may not be sufficient to revitalize a distressed area. To accomplish revitalization, it may be necessary to employ a land banking approach. Land banking involves acquiring key properties, holding and improving properties, and conveying properties to private developers with conditions in pursuit of a revitalization strategy. The land banking approach is described in my blog post, How a North Carolina Local Government Can Operate a Land Bank for Redevelopment. Some local governments have established redevelopment areas to aid in the revitalization process. Urban redevelopment areas are described in my blog post, Using a Redevelopment Area to Attract Private Investment.

A program at the School of Government, the Development Finance Initiative (DFI), was created to assist local governments with attracting private investment to accomplish their community and economic development goals. Many DFI projects are undertaken with the goal of revitalizing a distressed area with vacant or underutilized structures. Examples of DFI projects can be reviewed here.

[1] HUD – Evidence Matters, Vacant and Abandoned Properties: Turning Liabilities Into Assets (Winter 2014); Accordino & Johnson, Addressing the Vacant and Abandoned Property Problem, Journal of Urban Affairs 22:3, 302–3 (2002)).

[2] A-S-P Associates v. City of Raleigh, 298 N.C. 207 (1979).

[3] 305 N.C. 520 (1982). The reasonableness of aesthetic regulations is determined on a case-by-case basis by examining “whether the aesthetic purpose to which the regulation is reasonably related outweighs the burdens imposed on the private property owner by the regulation.” Id. at 530-01.

[4] Mulligan, Residential Rental Property Inspections, Permits, and Registration: Changes for 2017, Community and Economic Development Bulletin #9, available for download here. Question 18 in the bulletin explains that recent changes to periodic inspections statutes apply only to residential units, not nonresidential structures.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.