|

|

Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves Lives, Money, and PropertyBy Brian DabsonPublished March 6, 2018

Since 2000, North Carolina has received 17 Federal Major Disaster Declarations of which five were responses to hurricanes (Matthew, 2016; Irene, 2011; Ophelia, 2005; Ivan, 2004: and Isobel, 2003). Together these declarations triggered nearly $700 million of federal public assistance to communities, $230 million to individuals and households, with over 80,000 people receiving financial help. Hurricane Matthew alone accounted for over a third of these impacts. Despite the regularity of these disasters and the increasing scale of destruction, it is hard for governments, businesses, and households to appreciate the economic case for taking action to protect against future natural hazards.

Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves examines the benefits and costs of mitigation achievable by exceeding existing code provisions (1) and through federal mitigation grants (2). The headline findings are that federal mitigation grants save $6 for every dollar spent and building beyond code requirements saves $4 for every dollar spent. Without delving too deeply into the methodology used, costs include those for the up-front construction and long-term maintenance of improving existing facilities or the additional costs of building new facilities better. They also include health impacts, lost wages, lost business productivity, and pain and suffering. Benefits are the value of the reduction in future losses that mitigation provides. For exceeding existing code provisions, the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) varies from 7:1 ($7 benefit for every dollar invested) for hurricane surge to 4:1 for earthquake and wildland-urban interface fire mitigation. For the impact of federal grants, the range is from 7:1 for riverine flood to 3:1 for earthquake and wildland-urban interface fire mitigation. These BCRs vary across the country with the degree of vulnerability to different hazards. In North Carolina, new construction built two to ten feet above base flood elevation can yield a BCR ranging from 12.6:1 to 5.2:1. Buildings designed to IBHS FORTIFIED Home Hurricane standards can be cost-effective at the bronze level (3) for the central and eastern part of North Carolina, and at the silver (4) level for coastal counties. The report argues that mitigation investments bring net benefits to developers, title holders, lenders, tenants, and the community when code requirements are exceeded. Strategies to exceed minimum requirements of the 2015 Codes include building new homes:

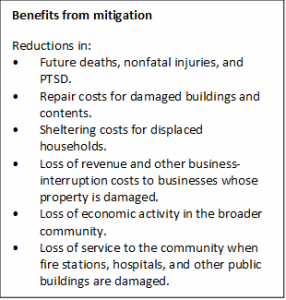

If all new buildings were built to such optimal design requirements for one year, there would be savings of approximately $4 in avoided future losses for every additional dollar spent up-front. These measures are estimated to prevent approximately 32,000 nonfatal injuries, 20 deaths and 100 cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Every state has received federal mitigation investments over the past 23 years, with states such as North Carolina receiving over $1 billion in benefits. The report estimates that society will ultimately save $6 for every $1 spent on up-front mitigation costs. Approximately 1 million nonfatal injuries, 600 deaths and 4,000 cases of PTSD will be prevented. Public-sector mitigation strategies funded through federal grants include:

Through such mitigation measures and their associated benefit-cost ratios, the National Institute of Building Sciences believes that decision makers will have the tools to understand the economic arguments around various development choices and avoid poor decisions that may place undue burdens on the community. Although these measures in of themselves are neither novel nor necessarily controversial, there is sometimes strong resistance to their adoption because of the additional costs involved. Mitigation Saves provides data to show that incurring such costs will yield strong rates of return to society. The trick now is to identify those incentives, whether public (tax breaks, loans, grants) or private (insurance premiums, market pressures) that will get everyone on board to save lives, money, and property.

(1) 2015 International Building Code (IBC), 2015 International Residential Code (IRC), and the 2015 International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC). (2) Impacts of 23 years of mitigation grants from Federal Emergency Management Association (FEMA), Economic Development Administration (EDA), and Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD). (3) FORTIFIED bronze level provides protection for the roof system. (4) FORTIFIED silver level provides protection for the roof system, windows, doors, and attached structures. |

Published March 6, 2018 By Brian Dabson

In December 2017, the National Institute of Building Sciences published Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2017 Interim Report. This report shows that acting to reduce the impacts of floods, hurricane surges, wind, earthquakes, and wildfires is a sound financial investment. Such action, often called mitigation, can result in significant savings of lives, money, and property. The Institute’s objective is to provide information to key decision-makers at federal, state, and local levels so they can develop more resilient communities that can better withstand natural disasters. This post summarizes the report’s findings.

In December 2017, the National Institute of Building Sciences published Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2017 Interim Report. This report shows that acting to reduce the impacts of floods, hurricane surges, wind, earthquakes, and wildfires is a sound financial investment. Such action, often called mitigation, can result in significant savings of lives, money, and property. The Institute’s objective is to provide information to key decision-makers at federal, state, and local levels so they can develop more resilient communities that can better withstand natural disasters. This post summarizes the report’s findings.

Since 2000, North Carolina has received 17 Federal Major Disaster Declarations of which five were responses to hurricanes (Matthew, 2016; Irene, 2011; Ophelia, 2005; Ivan, 2004: and Isobel, 2003). Together these declarations triggered nearly $700 million of federal public assistance to communities, $230 million to individuals and households, with over 80,000 people receiving financial help. Hurricane Matthew alone accounted for over a third of these impacts. Despite the regularity of these disasters and the increasing scale of destruction, it is hard for governments, businesses, and households to appreciate the economic case for taking action to protect against future natural hazards.

Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves examines the benefits and costs of mitigation achievable by exceeding existing code provisions (1) and through federal mitigation grants (2). The headline findings are that federal mitigation grants save $6 for every dollar spent and building beyond code requirements saves $4 for every dollar spent.

Without delving too deeply into the methodology used, costs include those for the up-front construction and long-term maintenance of improving existing facilities or the additional costs of building new facilities better. They also include health impacts, lost wages, lost business productivity, and pain and suffering. Benefits are the value of the reduction in future losses that mitigation provides. For exceeding existing code provisions, the benefit-cost ratio (BCR) varies from 7:1 ($7 benefit for every dollar invested) for hurricane surge to 4:1 for earthquake and wildland-urban interface fire mitigation. For the impact of federal grants, the range is from 7:1 for riverine flood to 3:1 for earthquake and wildland-urban interface fire mitigation.

These BCRs vary across the country with the degree of vulnerability to different hazards. In North Carolina, new construction built two to ten feet above base flood elevation can yield a BCR ranging from 12.6:1 to 5.2:1. Buildings designed to IBHS FORTIFIED Home Hurricane standards can be cost-effective at the bronze level (3) for the central and eastern part of North Carolina, and at the silver (4) level for coastal counties.

The report argues that mitigation investments bring net benefits to developers, title holders, lenders, tenants, and the community when code requirements are exceeded. Strategies to exceed minimum requirements of the 2015 Codes include building new homes:

- Higher than base flood elevation (BFE) required by the 2015 International Building Code to protect against riverine flooding and hurricane surge.

- To comply with the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) FORTIFIED Home Hurricane standards to give greater resistance to hurricanes.

- Stronger and stiffer than required by the 2015 International Building Code to better withstand earthquakes.

- To resist wildfires in the wildland-urban interface by complying with the 2015 International Wildland-Urban Interface Code.

If all new buildings were built to such optimal design requirements for one year, there would be savings of approximately $4 in avoided future losses for every additional dollar spent up-front. These measures are estimated to prevent approximately 32,000 nonfatal injuries, 20 deaths and 100 cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Every state has received federal mitigation investments over the past 23 years, with states such as North Carolina receiving over $1 billion in benefits. The report estimates that society will ultimately save $6 for every $1 spent on up-front mitigation costs. Approximately 1 million nonfatal injuries, 600 deaths and 4,000 cases of PTSD will be prevented. Public-sector mitigation strategies funded through federal grants include:

- Acquiring or demolishing flood-prone buildings, especially single-family dwellings, manufactured homes, and 2- to 4-family dwellings.

- Adding shutters, safe rooms and other common measures to increase wind resistance.

- Strengthening various structural and nonstructural components to resist the effects of earthquakes.

- Replacing roofs, managing vegetation to reduce fuels, and replacing wooden water tanks to protect against wildfires.

Through such mitigation measures and their associated benefit-cost ratios, the National Institute of Building Sciences believes that decision makers will have the tools to understand the economic arguments around various development choices and avoid poor decisions that may place undue burdens on the community. Although these measures in of themselves are neither novel nor necessarily controversial, there is sometimes strong resistance to their adoption because of the additional costs involved. Mitigation Saves provides data to show that incurring such costs will yield strong rates of return to society. The trick now is to identify those incentives, whether public (tax breaks, loans, grants) or private (insurance premiums, market pressures) that will get everyone on board to save lives, money, and property.

(1) 2015 International Building Code (IBC), 2015 International Residential Code (IRC), and the 2015 International Wildland-Urban Interface Code (IWUIC).

(2) Impacts of 23 years of mitigation grants from Federal Emergency Management Association (FEMA), Economic Development Administration (EDA), and Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD).

(3) FORTIFIED bronze level provides protection for the roof system.

(4) FORTIFIED silver level provides protection for the roof system, windows, doors, and attached structures.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.