|

|

The 2019 Hurricane Season Is Here: Now What?By Brian DabsonPublished July 9, 2019“[I]t is critical to learn from events such as Florence, to minimize the damages and streamline the response and recovery for the next storm…The growing economic and human costs of these events require that we not only change how we respond, but do so far more quickly than we have in the past.” This is one of the conclusions from a recent report from insurance company, Zurich North America, which commissioned a report on the lessons from Hurricane Florence for North Carolina. The 2019 hurricane season officially began on June 1, yet it is only nine months since Hurricane Florence brought a record-breaking storm surge of 9-13 feet and rainfall of 20-30 inches producing widespread, life-threatening flooding across eastern North Carolina[1]. There were over 50 fatalities, 5,000 evacuations and rescues, 15,000 seeking emergency shelter, and $17 billion in damages to homes and businesses[2]. FEMA has approved $1.3 billion of Federal funds to help clean-up and recovery[3]. In the month of June 2019 alone, FEMA and the State of North Carolina announced payments of $12.8 million to local governments for debris removal, electric cooperatives for the repair of electrical systems, and other public agencies for repairs and clean-up[4]. All this comes just two years after Hurricane Matthew, which devastated many communities and triggered planning and actions to make the state less vulnerable and more resilient to major disasters. During 2018, North Carolina Emergency Management and FEMA approved awards of over $88 million through its Hurricane Matthew Hazard Mitigation Grant Program to elevate, reconstruct or buy-out 680 homes across the state. Earlier this month it was announced that Edgecombe County will receive $1.1 million from the same program to study the feasibility of elevating 75 homes in Princeville that are at risk from repeat flooding. To better coordinate disaster recovery, the Department of Public Safety has created a new Office of Recovery and Resiliency, and recently announced the appointment of a Chief Resilience Officer. Dr. Jessica Whitehead’s role is to lead the state’s initiative to help storm-impacted communities rebuild smarter and stronger in the face of future natural disasters and long-term climate change. This is no small task and will require large-scale goodwill and collaboration across public agencies, the private sector, and local communities, as well as long-term and substantial investment. Certainly, the to-do list is long and there is no shortage of advice. An earlier blog reviewed a National Institute of Building Sciences report[5] which presents the clear benefits of investments in hazard mitigation. However, it also notes the continued strong resistance to their adoption partly because of the perceived costs involved and skepticism for their need. A recent study[6] from the insurance group, Zurich North America, looks for lessons to be learned from the aftermath of Hurricane Florence in North Carolina, and in so doing expands upon the Institute’s findings. All who are charged with disaster response and recovery should it find it worthwhile to consider the study’s observations, four of which are summarized below.

So, what do the report’s authors recommend? We need to:

All this clearly suggests that while the appointment of a Chief Resilience Officer is a positive, much-needed step, making North Carolina more resilient is everyone’s job…and it is urgent. [1] National Weather Service, www.weather.gov. [2] North Carolina State Office of Budget and Management, October 26, 2018. “Hurricane Florence Recovery Recommendations.” [5] National Institute of Building Sciences (2017), Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2017 Interim Report. [6] Norton, R., MacClune, K., Szönyi, M. and Schneider, J. (2019). Hurricane Florence: Building Resilience for the New Normal. Schaumburg, IL: Zurich American Insurance Company. |

Published July 9, 2019 By Brian Dabson

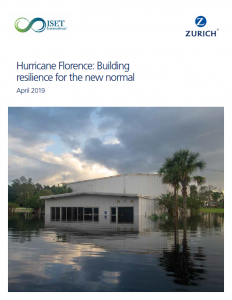

“[I]t is critical to learn from events such as Florence, to minimize the damages and streamline the response and recovery for the next storm…The growing economic and human costs of these events require that we not only change how we respond, but do so far more quickly than we have in the past.” This is one of the conclusions from a recent report from insurance company, Zurich North America, which commissioned a report on the lessons from Hurricane Florence for North Carolina.

The 2019 hurricane season officially began on June 1, yet it is only nine months since Hurricane Florence brought a record-breaking storm surge of 9-13 feet and rainfall of 20-30 inches producing widespread, life-threatening flooding across eastern North Carolina[1]. There were over 50 fatalities, 5,000 evacuations and rescues, 15,000 seeking emergency shelter, and $17 billion in damages to homes and businesses[2]. FEMA has approved $1.3 billion of Federal funds to help clean-up and recovery[3]. In the month of June 2019 alone, FEMA and the State of North Carolina announced payments of $12.8 million to local governments for debris removal, electric cooperatives for the repair of electrical systems, and other public agencies for repairs and clean-up[4].

All this comes just two years after Hurricane Matthew, which devastated many communities and triggered planning and actions to make the state less vulnerable and more resilient to major disasters. During 2018, North Carolina Emergency Management and FEMA approved awards of over $88 million through its Hurricane Matthew Hazard Mitigation Grant Program to elevate, reconstruct or buy-out 680 homes across the state. Earlier this month it was announced that Edgecombe County will receive $1.1 million from the same program to study the feasibility of elevating 75 homes in Princeville that are at risk from repeat flooding.

To better coordinate disaster recovery, the Department of Public Safety has created a new Office of Recovery and Resiliency, and recently announced the appointment of a Chief Resilience Officer. Dr. Jessica Whitehead’s role is to lead the state’s initiative to help storm-impacted communities rebuild smarter and stronger in the face of future natural disasters and long-term climate change. This is no small task and will require large-scale goodwill and collaboration across public agencies, the private sector, and local communities, as well as long-term and substantial investment. Certainly, the to-do list is long and there is no shortage of advice.

An earlier blog reviewed a National Institute of Building Sciences report[5] which presents the clear benefits of investments in hazard mitigation. However, it also notes the continued strong resistance to their adoption partly because of the perceived costs involved and skepticism for their need. A recent study[6] from the insurance group, Zurich North America, looks for lessons to be learned from the aftermath of Hurricane Florence in North Carolina, and in so doing expands upon the Institute’s findings. All who are charged with disaster response and recovery should it find it worthwhile to consider the study’s observations, four of which are summarized below.

- Lived experience, even repeat experience, doesn’t make people act. Although residents, businesses, nonprofits, and governments have made some adjustments in response to the impacts of Hurricanes Matthew and Florence, action that requires broader coordination, political risk, or significant financial investment has been limited. Real estate along the coasts is booming despite the threat of sea level rise, and ash ponds are being cleaned up and hog farms relocated out of the floodplain far too slowly. The report notes, “There is still little public appetite for widespread, decisive action to invest in broad, multi-scalar, multi-sectoral risk reduction. Unfortunately, it may take another Florence before people are willing to voluntarily make difficult decisions.”

- As a nation, we continue to support high-risk investments and unsustainable development. One of the consequences of the National Flood Insurance Program is that property owners with NFIP policies are receiving public subsidies to live in high-risk areas. This has encouraged more homes and businesses to locate in such areas, leading in turn to increased state and federal government investment to protect and maintain them.

- An improved and consistent approach is needed to address large concentrations of harmful waste located in high hazard areas. Hurricane Florence highlighted the lack of enforcement of coal ash storage waste and hog waste in North Carolina. The report calls for a proactive approach to identifying and mitigating the spread of these waste products during floods to avoid potential environmental catastrophes in the future.

- Floods contribute to marginalizing vulnerable communities in multiple ways. Floods and other hazards often hit the most marginalized communities hardest. Poorer communities also disproportionately bear the impacts of living near pollution sources such as power plants, landfills, hazardous waste sites and on less expensive land which can be more vulnerable to flooding. A lack of resources and financial capital makes it difficult to recover and rebuild.

So, what do the report’s authors recommend?

We need to:

- Act now. Failure to do so will be far more expensive in the long run.

- Critically assess where we are building and how we are incentivizing risk. Incentives should encourage development in safe areas, not in harm’s way.

- Shift from siloed interventions to a holistic approach. Risks must be addressed systemically so that actions to address one problem do not create more problems for others.

- Change how we communicate risk. The way we describe the strength of hurricanes or the likelihood of floods understates risk and can lead to poor decisions.

- Treat insurance as being a necessary but not a sufficient way to reduce risk. Other measures are needed to safeguard lives and property.

- Imagine how bad it could be and plan for worse.

All this clearly suggests that while the appointment of a Chief Resilience Officer is a positive, much-needed step, making North Carolina more resilient is everyone’s job…and it is urgent.

[1] National Weather Service, www.weather.gov.

[2] North Carolina State Office of Budget and Management, October 26, 2018. “Hurricane Florence Recovery Recommendations.”

[5] National Institute of Building Sciences (2017), Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves: 2017 Interim Report.

[6] Norton, R., MacClune, K., Szönyi, M. and Schneider, J. (2019). Hurricane Florence: Building Resilience for the New Normal. Schaumburg, IL: Zurich American Insurance Company.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.