|

| ||

How to Define a Retail Trade Area and an Office and Multifamily Market Area in a Small TownBy CED Guest AuthorPublished November 8, 2021The School of Government’s Development Finance Initiative (DFI) was founded in part to provide specialized assistance to help small towns in North Carolina attract private investment and spur revitalization efforts. A key part of DFI’s process is to evaluate the type and scale of development that the local market could support. A foundational first step in this analysis is to define the limits of the market, or in more technical terms, the retail trade area and residential and office market areas. Where could a potential development draw demand from and what other properties is it competing with? Commercial real estate databases and national-scale brokerage firms will often outline their own trade areas for large communities. However, small communities that haven’t had recent developments may have never had their trade area defined. Though not an exact science – two market analysts will often define a trade area differently — the ability to articulate and justify a trade area can help a small community win interest from developers who may otherwise be unfamiliar with a community’s development potential. A developer seeking real estate development opportunities in an unfamiliar or untested market will want to understand the market potential of a site they are considering purchasing. For example, developers may consider:

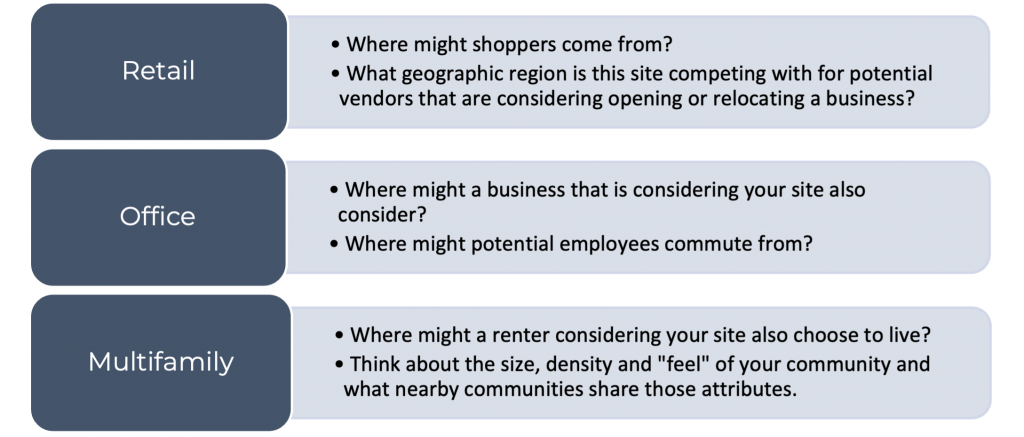

However, this critical market context is dependent on the developer understanding a particular site’s market and trade areas. Insights from local real estate brokers, community and economic development professionals and other stakeholders are particularly helpful in identifying these geographic areas. For small communities that want to convince developers to build locally, defining the market and trade areas can provide a great first step in demonstrating market potential. Begin this process by researching where potential demand for a site might come from and what sites it would compete with (see Figure 1). Figure 1: Guiding Questions to Determine Retail Trade and Office/Multifamily Market Areas Consider the decisions that a developer’s target customers will make in determining their preferred location for shopping, living, and working. Consumer decisions can be influenced by factors such as:

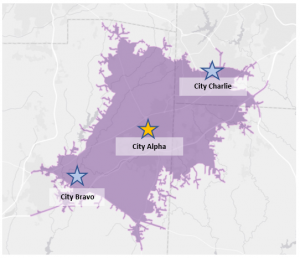

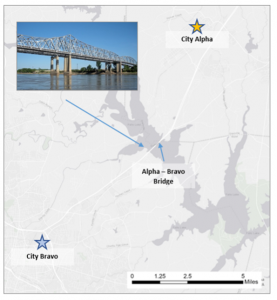

As an example, consider the map below (Figure 2) showing a bridge connecting the fictional cities of Alpha and Bravo. Suppose the bridge is approximately one mile long, and often congested. Residents of City Alpha may have a perceived barrier of crossing a body of water to run errands or may simply wish to avoid the traffic. The retail trade area would then exclude the shopping centers southwest of the bridge.

Figure 2: Bridge Barrier for “City Alpha” Retail Trade Area

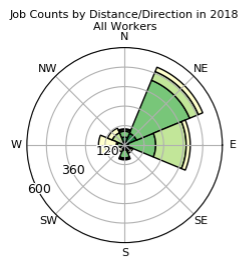

Figure 3: Distance & Direction of Commute for Residents of “City Alpha”, 2018

Source (Figure 3): U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies via LEHD On-the-Map

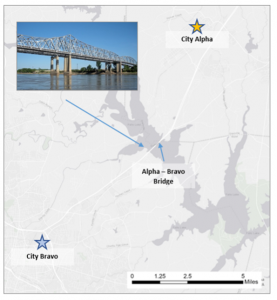

Consider the map below, which illustrates a 15-minute drive-time radius from Alpha City (in purple). While potential shoppers may be willing to travel 15 minutes to access retail opportunities, this 15-minute drive-time includes parts of Bravo City and Charlie City which have their own retail shopping nodes. The Alpha retail trade area should reflect these competing markets.

Figure 4: “Alpha City” 15-Minute Drive Time Source: North Carolina DOT, Esri, HERE, Garmin, USGS, NGA, EPA, USDA, NPS via ESRI ArcMap Online Providing detailed local knowledge of geographic barriers, current shopping and commuting patterns and the competing markets that shape a community’s retail trade and office and multifamily market areas can help demonstrate the market potential of a site. This in turn can help attract new investment to an otherwise untested market.

Amelie Bailey is a Real Estate Development Analyst with the UNC School of Government’s Development Finance Initiative. | ||

Published November 8, 2021 By CED Guest Author

The School of Government’s Development Finance Initiative (DFI) was founded in part to provide specialized assistance to help small towns in North Carolina attract private investment and spur revitalization efforts. A key part of DFI’s process is to evaluate the type and scale of development that the local market could support. A foundational first step in this analysis is to define the limits of the market, or in more technical terms, the retail trade area and residential and office market areas. Where could a potential development draw demand from and what other properties is it competing with? Commercial real estate databases and national-scale brokerage firms will often outline their own trade areas for large communities. However, small communities that haven’t had recent developments may have never had their trade area defined. Though not an exact science – two market analysts will often define a trade area differently — the ability to articulate and justify a trade area can help a small community win interest from developers who may otherwise be unfamiliar with a community’s development potential.

A developer seeking real estate development opportunities in an unfamiliar or untested market will want to understand the market potential of a site they are considering purchasing. For example, developers may consider:

- Existing Supply – the quantity, quality, and types of properties that already exist in the market as well as any properties in the development pipeline. This information helps a developer understand their competition in a market and whether there is demand for new commercial space or multifamily apartment units.

- Comparable Properties – existing properties in the trade or market area that share key characteristics (such as build type, quality, and amenities) to the type of property the developer would like to build. Knowing the performance of comparable properties helps developers understand the appropriate rent levels that could be charged for a commercial or residential property, as well as reasonable assumptions for both lease-up periods and ongoing vacancy rates. They might also research recent sales prices of comparable properties to understand potential revenue from sale of the property, and to understand whether the market is drawing interest from other developers and investors.

- Absorption Rates – how much space has been leased in a particular period less the space that has been vacated. This helps a developer understand whether there is unmet demand for new space in a market. Knowing this rate also helps developers understand how quickly new space is likely to lease-up upon completion.

- Demand Drivers for new commercial space or residential development in the market area. This could include household growth rates, current retail sales patterns, employment levels and economic development trends among others.

However, this critical market context is dependent on the developer understanding a particular site’s market and trade areas. Insights from local real estate brokers, community and economic development professionals and other stakeholders are particularly helpful in identifying these geographic areas. For small communities that want to convince developers to build locally, defining the market and trade areas can provide a great first step in demonstrating market potential.

Begin this process by researching where potential demand for a site might come from and what sites it would compete with (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Guiding Questions to Determine Retail Trade and Office/Multifamily Market Areas

Consider the decisions that a developer’s target customers will make in determining their preferred location for shopping, living, and working. Consumer decisions can be influenced by factors such as:

- Geographic barriers – This could include barriers from the built or natural environment. For example, high-traffic corridors or traffic bottleneck sites may create a manmade barrier that will constrain the size of a retail trade area. Natural geographic features like bodies of water, foothills and other features may create similar psychological barriers for shoppers – the site could seem further away or harder to access than it actually is. It may also be worth carefully considering municipal boundaries. Most consumers don’t factor in municipal boundaries when making their purchasing decisions but there are exceptions. For example, if a site is located on the border of two municipalities, one with a highly coveted school district, the municipal boundaries may influence the decisions of potential residents of an apartment complex.

As an example, consider the map below (Figure 2) showing a bridge connecting the fictional cities of Alpha and Bravo. Suppose the bridge is approximately one mile long, and often congested. Residents of City Alpha may have a perceived barrier of crossing a body of water to run errands or may simply wish to avoid the traffic. The retail trade area would then exclude the shopping centers southwest of the bridge.

Figure 2: Bridge Barrier for “City Alpha” Retail Trade Area

- Existing shopping and economic patterns – It’s important to understand existing consumer patterns and preferences. How long are local shoppers accustomed to driving to access their shopping destinations? Higher-density communities may have a smaller distance radius within which residents do all their shopping, whereas a consumer in a rural county may already travel 30 minutes or more to access shopping centers. For residential market areas, consider regional work commute patterns. A household considering your site will also likely consider other sites along their route to work or other sites that put them in similar proximity to their job. Similarly, households may want to use retail shopping locations that are along their route to work.

Say Figure 3 below describes the work commute patterns of the residents of the fictional City Alpha. The graph shows that the majority of workers are heading east or northeast to get to work. A household considering renting an apartment in Alpha City would likely also consider other communities similar to Alpha nearby or east/northeast of Alpha along their routes to work.

Figure 3: Distance & Direction of Commute for Residents of “City Alpha”, 2018

|

|

Source (Figure 3): U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies via LEHD On-the-Map

- Competing markets – While any site is likely to have nearby comparable properties that may compete, it is important to understand when existing retail, office or residential nodes command their own market area. Existing commercial nodes may serve as anchor centers that draw their own radius of consumers. A small-scale downtown-oriented site may not be able to draw shoppers that are near an existing town center development. These existing nodes and their market and trade areas should be noted and carved out of your site’s trade and market areas.

Consider the map below, which illustrates a 15-minute drive-time radius from Alpha City (in purple). While potential shoppers may be willing to travel 15 minutes to access retail opportunities, this 15-minute drive-time includes parts of Bravo City and Charlie City which have their own retail shopping nodes. The Alpha retail trade area should reflect these competing markets.

Figure 4: “Alpha City” 15-Minute Drive Time

Source: North Carolina DOT, Esri, HERE, Garmin, USGS, NGA, EPA, USDA, NPS via ESRI ArcMap Online

Providing detailed local knowledge of geographic barriers, current shopping and commuting patterns and the competing markets that shape a community’s retail trade and office and multifamily market areas can help demonstrate the market potential of a site. This in turn can help attract new investment to an otherwise untested market.

Amelie Bailey is a Real Estate Development Analyst with the UNC School of Government’s Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.