|

|

Student Corner: 3 Things You Should Know about Social Impact BondsBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished August 5, 2014

If you’re still wondering what a SIB is, here are three things that you should know: 1. SIBs are not actually bonds. Social impact bonds represent aggregated capital from financiers (investment banks, private foundations, high net worth individuals, etc.) that is invested towards scaling up proven interventions that have a measurable impact on enhancing outcomes for the targeted population. This investment is managed by an intermediary organization that also administers performance contracts between the service provider and the government. Unlike bonds, which are debt instruments, SIBs have characteristics of both debt and equity products. Investors stand to lose their principal in the event that an independent evaluator finds that the intervention did not achieve its targets because, in that situation, the government does not have to repay the principal. However, if evaluation demonstrates that the intervention exceeds performance metrics, then the government repays the principal and a pre-negotiated premium. 2. SIBs represent an additional tool in the toolbox for scaling up solutions to complex—and costly—social and health issues. Social impact bonds build on outcomes-based, government contracting approaches championed within the Pay for Success (PFS) movement and introduces financing innovations that enable commercial and philanthropic investors to assume the risks and double-bottom line benefits involved with launching PFS projects. SIBs formally started in the United Kingdom as a pilot to finance service delivery to 3,000 males serving prison sentences in Peterborough, England. After raising nearly $8 million from 17 social investors to pay for upfront program costs, the British government contracted to reimburse investors based on the net savings accrued to government agencies resulting from reductions in recidivism. After extensive studies and cost/benefit analysis, the government determined that a 7.5 percent reduction in re-offense over six years would generate sufficient savings to repay the investors and is willing to enhance returns by 13 percent if the intervention exceeds the target. The Peterborough SIB was launched in 2010 and is still ongoing. In the meantime, this promising approach has attracted the support of researchers, governments, and philanthropic investors who are supporting the development of similar pilots across the country. The City of New York is currently implementing the nation’s first SIB to help rehabilitate juveniles detained at Rikers Island thanks to a $9.6 million loan from Goldman Sachs Bank’s Urban Investment Group. Similarly, the Rockefeller Foundation has also partnered with the Harvard Kennedy School to launch the Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab, which has engaged staff to provide pro bono assistance to ten state and local governments seeking to implement PFS contracts using SIBs. The following illustration was produced by Social Finance US (a leading SIB intermediary organization) and shows cities and states where SIBs are gaining traction. (2014) Social Finance US 3. Not every intervention is appropriate for SIB financing. Colloquial wisdom tells us that the costs of effective preventative treatments often pale in comparison to those associated with treating chronic problems, and the same logic applies to PFS contracts and SIB financing. In order for governments to accrue the cost savings necessary to attract SIB investors, this approach should target issues where: interventions can be scaled to assist a significant population, savings can be reaped to a specific agency and/or public budget item, and programs/services are evidence-based and proven to prevent the costs associated with remedial interventions. The social and economic costs of recidivism are well-documented, which facilitated the development of the SIBs in Peterborough and New York City, and other cities are exploring the use of SIBs to reduce costs in other areas, such as child asthma treatment, providing supportive housing and case management for chronically homeless individuals, and improving outcomes for children of low-income, first-time mothers. SIBs are a promising financial innovation and the evolution of this approach and the outcomes of the aforementioned pilots offer much to learn. The following organizations have great resources if you want to learn more about social impact bonds and pay for success contracting:

Meisha McDaniel is a dual degree Master’s candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning and the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill. She is also a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. |

Published August 5, 2014 By CED Program Interns & Students

Recent state and federal-level budget talks often stress that public funding is insufficient to adequately address pressing social issues that prevent capable citizens from fully participating in our economy. However, an emergent, long-term approach to financing social and health service delivery is gaining momentum—social impact bonds, or SIBs. Even though no formal SIB pilot has been launched in North Carolina, to date, organizations like the Nonprofit Finance Fund, which hosted a workshop in Charlotte targeted towards early childhood service providers, are already exploring how to build the capacity necessary to implement SIB-backed programs throughout the country.

Recent state and federal-level budget talks often stress that public funding is insufficient to adequately address pressing social issues that prevent capable citizens from fully participating in our economy. However, an emergent, long-term approach to financing social and health service delivery is gaining momentum—social impact bonds, or SIBs. Even though no formal SIB pilot has been launched in North Carolina, to date, organizations like the Nonprofit Finance Fund, which hosted a workshop in Charlotte targeted towards early childhood service providers, are already exploring how to build the capacity necessary to implement SIB-backed programs throughout the country.

If you’re still wondering what a SIB is, here are three things that you should know:

1. SIBs are not actually bonds.

Social impact bonds represent aggregated capital from financiers (investment banks, private foundations, high net worth individuals, etc.) that is invested towards scaling up proven interventions that have a measurable impact on enhancing outcomes for the targeted population. This investment is managed by an intermediary organization that also administers performance contracts between the service provider and the government.

Unlike bonds, which are debt instruments, SIBs have characteristics of both debt and equity products. Investors stand to lose their principal in the event that an independent evaluator finds that the intervention did not achieve its targets because, in that situation, the government does not have to repay the principal. However, if evaluation demonstrates that the intervention exceeds performance metrics, then the government repays the principal and a pre-negotiated premium.

2. SIBs represent an additional tool in the toolbox for scaling up solutions to complex—and costly—social and health issues.

Social impact bonds build on outcomes-based, government contracting approaches championed within the Pay for Success (PFS) movement and introduces financing innovations that enable commercial and philanthropic investors to assume the risks and double-bottom line benefits involved with launching PFS projects.

SIBs formally started in the United Kingdom as a pilot to finance service delivery to 3,000 males serving prison sentences in Peterborough, England. After raising nearly $8 million from 17 social investors to pay for upfront program costs, the British government contracted to reimburse investors based on the net savings accrued to government agencies resulting from reductions in recidivism. After extensive studies and cost/benefit analysis, the government determined that a 7.5 percent reduction in re-offense over six years would generate sufficient savings to repay the investors and is willing to enhance returns by 13 percent if the intervention exceeds the target.

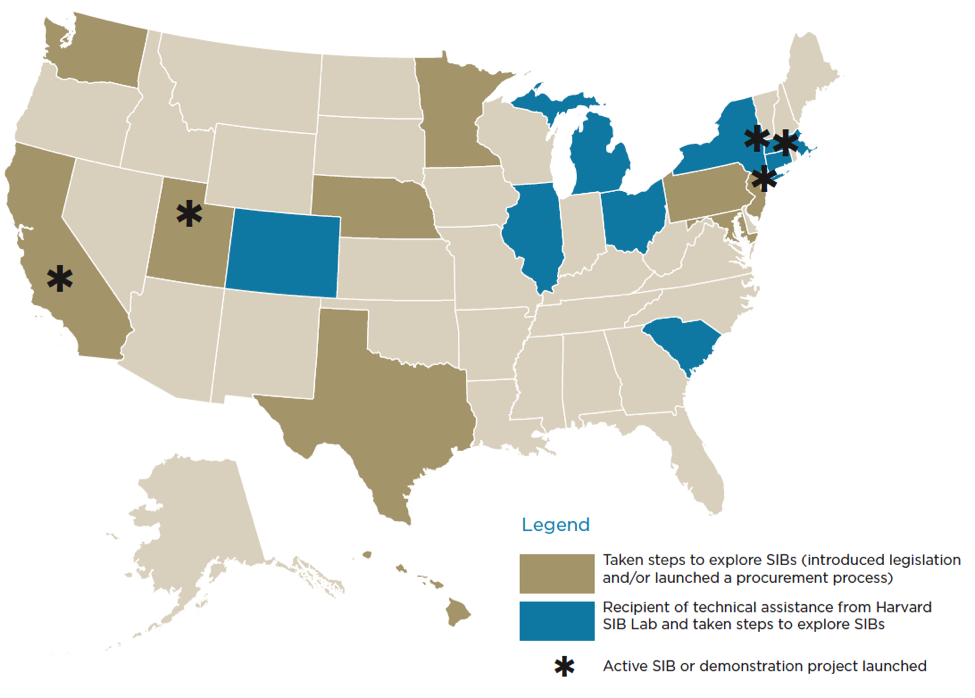

The Peterborough SIB was launched in 2010 and is still ongoing. In the meantime, this promising approach has attracted the support of researchers, governments, and philanthropic investors who are supporting the development of similar pilots across the country. The City of New York is currently implementing the nation’s first SIB to help rehabilitate juveniles detained at Rikers Island thanks to a $9.6 million loan from Goldman Sachs Bank’s Urban Investment Group. Similarly, the Rockefeller Foundation has also partnered with the Harvard Kennedy School to launch the Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab, which has engaged staff to provide pro bono assistance to ten state and local governments seeking to implement PFS contracts using SIBs. The following illustration was produced by Social Finance US (a leading SIB intermediary organization) and shows cities and states where SIBs are gaining traction.

(2014) Social Finance US

3. Not every intervention is appropriate for SIB financing.

Colloquial wisdom tells us that the costs of effective preventative treatments often pale in comparison to those associated with treating chronic problems, and the same logic applies to PFS contracts and SIB financing. In order for governments to accrue the cost savings necessary to attract SIB investors, this approach should target issues where: interventions can be scaled to assist a significant population, savings can be reaped to a specific agency and/or public budget item, and programs/services are evidence-based and proven to prevent the costs associated with remedial interventions.

The social and economic costs of recidivism are well-documented, which facilitated the development of the SIBs in Peterborough and New York City, and other cities are exploring the use of SIBs to reduce costs in other areas, such as child asthma treatment, providing supportive housing and case management for chronically homeless individuals, and improving outcomes for children of low-income, first-time mothers.

SIBs are a promising financial innovation and the evolution of this approach and the outcomes of the aforementioned pilots offer much to learn. The following organizations have great resources if you want to learn more about social impact bonds and pay for success contracting:

- Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco: http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/publications/community-development-investment-review/2013/april/pay-for-success-financing/

- Harvard Kennedy School Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab: http://hks-siblab.org/

- Nonprofit Finance Fund: http://payforsuccess.org/

- Social Finance: http://socialfinanceus.org/social-impact-financing/social-impact-bonds/what-social-impact-bond.

Meisha McDaniel is a dual degree Master’s candidate in the Department of City and Regional Planning and the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill. She is also a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.

One Response to “Student Corner: 3 Things You Should Know about Social Impact Bonds”

Social Impact Bonds: A Magic Tool for Financing Innovation? - Death and Taxes

[…] Here is a nice summary of three common mistakes about SIBs to provide some additional background, like they are not bonds. […]