|

|

Student Corner: A Closer Look at Multifamily Construction TypesBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished May 18, 2017

The first thing to understand about commercial construction is that all construction is governed by building code. As the previous post touched on, most municipalities, including all those in the state of North Carolina, require buildings to be designed and constructed compliant with the International Building Code (IBC). Furthermore, the IBC delineates between different construction types. In total, there are five main categories of construction types, with several sub-categories. However, the primary difference between the five major construction types is the fire-resistance of the materials used to construct the building. For example, Type I buildings are typically built from concrete and steel, whereas Type III buildings are usually constructed using wood. Additionally, the IBC also limits the maximum height of a building depending on the construction type, as well as its intended use. The Metropolitan was what is commonly referred to as a “podium structure,” meaning that the first floor was built using concrete, whereas the upper floors were built using wood. This is a common type of construction especially in urban settings where retail businesses (which often require greater floor-to-ceiling heights) are located on the first floor with residential units above. Based on the type of materials used during construction and the proposed height of the structure, we can conclude that The Metropolitan was a Type III A building. Therefore, using Table 1, we see that the minimum fire-resistance for the structural frame is one hour. This means that the building’s structure must be able to withstand exposure to an open flame for at least one hour before failing. Contrast this with a Type I A building, which the IBC dictates must be fire-resistant for up to three hours. So at this point, you may be wondering why developers and architects opt to design and build anything other than Type I structures. And the answer is simple, and likely unsurprising: cost. Building a Type I structure is extremely cost-prohibitive due to the relatively high cost of reinforced concrete construction when compared to wood-framed, or “stick built” construction. Further exasperating this problem is the fact that building with concrete takes longer and is more labor-intensive. Concrete doesn’t reach its full strength until 28 days after it is placed, which often has many scheduled-related ramifications. A local developer who is active in the Raleigh market confirmed that the cost to construct an apartment building compliant with Type I standards is about 25% more expensive than the cost to construct an otherwise-identical Type III building. A 25% increase in construction costs, especially when you’re talking about a project that can cost in the ballpark of $50M to $75M (The Metropolitan was projected to cost $51M), is an extremely difficult obstacle for a developer to overcome. This increase in construction cost would almost undeniably cause any real estate developer to walk away from a potential mid-rise (e.g. 5-stories and less) multifamily project unless they felt that they could recover this cost from prospective tenants in the form of rent increases. And for a city such as Raleigh, that recently made the list of cities with the fastest growing apartment rents in the country, this surely would not be well-received. It is important to emphasize, however, that the situation that arose at The Metropolitan was a case of unfortunate timing. The building had been designed and constructed (to that point) in complete compliance with the IBC. However, when the building caught fire on March 16th, it was at its most vulnerable state. To no fault of the general contractor, none of the fire protection measures that would normally be in place to prevent a fire of this magnitude from spreading, such as drywall, fire caulking, and sprinkler systems, had been installed yet. And while the pictures, videos and charred remains of the project serve as a frightening reminder of the havoc a fire can wreak on the built environment, it’s important to realize that just because the building was constructed with wood, doesn’t make it unsafe. However, if the city and state officials feel the need to require real estate developers to build the most fire-resistant structures possible, they must also be prepared to deal with one of two associated consequences: a shortage of new residential units, or rising rents. Zach Spencer is a first-year MBA student concentrating in Real Estate Development at the UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School in Chapel Hill. He is currently a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. |

Published May 18, 2017 By CED Program Interns & Students

A recent blog post examined the benefits of wood-framed construction. However, in the few months that have lapsed between that article and this post, The Metropolitan, a 241-unit apartment building under development in Raleigh inexplicably caught fire and subsequently burned to the ground, causing severe damage to several adjacent buildings in the process. Due to the hard work and heroism of The Raleigh Fire Department, thankfully no loss of life occurred. However, the fact that this was the largest fire in the City of Raleigh for nearly a century has North Carolina residents wondering if wood-framed construction is really safe. So today, the CED blog will try to answer this question by examining different construction materials and the tradeoffs associated with each.

A recent blog post examined the benefits of wood-framed construction. However, in the few months that have lapsed between that article and this post, The Metropolitan, a 241-unit apartment building under development in Raleigh inexplicably caught fire and subsequently burned to the ground, causing severe damage to several adjacent buildings in the process. Due to the hard work and heroism of The Raleigh Fire Department, thankfully no loss of life occurred. However, the fact that this was the largest fire in the City of Raleigh for nearly a century has North Carolina residents wondering if wood-framed construction is really safe. So today, the CED blog will try to answer this question by examining different construction materials and the tradeoffs associated with each.

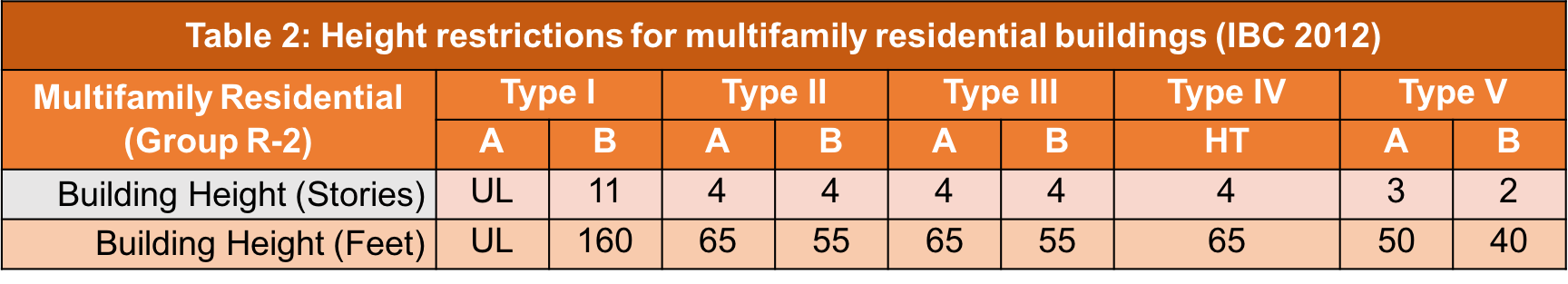

The first thing to understand about commercial construction is that all construction is governed by building code. As the previous post touched on, most municipalities, including all those in the state of North Carolina, require buildings to be designed and constructed compliant with the International Building Code (IBC). Furthermore, the IBC delineates between different construction types. In total, there are five main categories of construction types, with several sub-categories. However, the primary difference between the five major construction types is the fire-resistance of the materials used to construct the building. For example, Type I buildings are typically built from concrete and steel, whereas Type III buildings are usually constructed using wood. Additionally, the IBC also limits the maximum height of a building depending on the construction type, as well as its intended use.

The Metropolitan was what is commonly referred to as a “podium structure,” meaning that the first floor was built using concrete, whereas the upper floors were built using wood. This is a common type of construction especially in urban settings where retail businesses (which often require greater floor-to-ceiling heights) are located on the first floor with residential units above. Based on the type of materials used during construction and the proposed height of the structure, we can conclude that The Metropolitan was a Type III A building. Therefore, using Table 1, we see that the minimum fire-resistance for the structural frame is one hour. This means that the building’s structure must be able to withstand exposure to an open flame for at least one hour before failing. Contrast this with a Type I A building, which the IBC dictates must be fire-resistant for up to three hours.

So at this point, you may be wondering why developers and architects opt to design and build anything other than Type I structures. And the answer is simple, and likely unsurprising: cost. Building a Type I structure is extremely cost-prohibitive due to the relatively high cost of reinforced concrete construction when compared to wood-framed, or “stick built” construction. Further exasperating this problem is the fact that building with concrete takes longer and is more labor-intensive. Concrete doesn’t reach its full strength until 28 days after it is placed, which often has many scheduled-related ramifications.

A local developer who is active in the Raleigh market confirmed that the cost to construct an apartment building compliant with Type I standards is about 25% more expensive than the cost to construct an otherwise-identical Type III building. A 25% increase in construction costs, especially when you’re talking about a project that can cost in the ballpark of $50M to $75M (The Metropolitan was projected to cost $51M), is an extremely difficult obstacle for a developer to overcome. This increase in construction cost would almost undeniably cause any real estate developer to walk away from a potential mid-rise (e.g. 5-stories and less) multifamily project unless they felt that they could recover this cost from prospective tenants in the form of rent increases. And for a city such as Raleigh, that recently made the list of cities with the fastest growing apartment rents in the country, this surely would not be well-received.

It is important to emphasize, however, that the situation that arose at The Metropolitan was a case of unfortunate timing. The building had been designed and constructed (to that point) in complete compliance with the IBC. However, when the building caught fire on March 16th, it was at its most vulnerable state. To no fault of the general contractor, none of the fire protection measures that would normally be in place to prevent a fire of this magnitude from spreading, such as drywall, fire caulking, and sprinkler systems, had been installed yet. And while the pictures, videos and charred remains of the project serve as a frightening reminder of the havoc a fire can wreak on the built environment, it’s important to realize that just because the building was constructed with wood, doesn’t make it unsafe. However, if the city and state officials feel the need to require real estate developers to build the most fire-resistant structures possible, they must also be prepared to deal with one of two associated consequences: a shortage of new residential units, or rising rents.

Zach Spencer is a first-year MBA student concentrating in Real Estate Development at the UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School in Chapel Hill. He is currently a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.