|

|

Economic Development at the Top of the WorldBy Glenn BarnesPublished December 27, 2012

Quick trivia question—what is the northernmost town on earth? If you answered Santa’s Village, sorry. The man from the North Pole has had a busy week, but the actual answer is Longyearbyen in the Svalbard archipelago.  The Svalbard archipelago lies about 400 miles north of the northern coast of Norway, between 74 and 81 degrees north latitude, inside the Arctic Circle. Svalbard is administered by Norway and is led by a Governor. Longyearbyen (pronounced lung-yer-bin) is the largest town and seat of government for the islands.  The early visitors to Svalbard came in the 17th century for hunting, fishing, and whaling. Many polar expeditions were launched from Svalbard as well—Longyearbyen is roughly 800 miles from the North Pole. And coal mining became the islands’ largest industry in the early 1900s with major operations in Longyearbyen as well as the Soviet mining communities of Barentsburg and the now-abandoned Pyramiden.  Coal mining is still a major industry in Svalbard, led by Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK). So is scientific research. The world’s northernmost university center is in Longyearbyen, as is the Global Seed Vault. There is also a facility for the European Space Agency in Ny-Ålesund. But for the past 20 years the driving economic force in Svalbard has been the expansion of the tourism industry. Climate patterns give Svalbard temperatures higher than other land masses at similar latitudes, which makes it more friendly for visitors. Its proximity to the North Pole is undoubtedly a draw. Svalbard has many of the world’s “northernmost” sites including the northernmost church, museum, hotel, and Thai restaurant. Summers feature 24 hours of daylight, while the polar night skies are lit up by Aurora Borealis. Svalbard is far enough north that there are no trees, and reindeer literally wander the streets of the towns. Sixty-five percent of the archipelago is protected land, and 60 percent of the islands are covered in glaciers.  Perhaps the most iconic draw of Svalbard, though, is the polar bear. About one-sixth of the world’s polar bears live in Svalbard—they actually outnumber the people. While typically the only sightings of the bears in town are on the tourist signs, anyone leaving town boundaries is required to carry a registered firearm for protection.  The decision to expand tourism in Svalbard, which was laid out in 1990-1991’s Report No. 50, emphasized the need to develop tourism at a scale that would not threaten the area’s distinctive wilderness. Rather, that natural environment would become the focus of the tourism but with limits on the number of visitors, types of activities, and other potential stresses. Today, virtually all of the activities for visitors to Svalbard involve eco-tourism—boat trips through the fjords, dogsledding and snowmobile trips across the ice caps, hiking on glaciers, kayaking, and other outdoor activities.  The expansion of tourism also presented public administration challenges for Svalbard. Up until the late 1980s, Longyearbyen operated as a company town, with SNSK providing minimal services to its employees. The expansion of tourism also required the expansion of basic government services—hotels needed reliable heat and hot water, while employees needed schools for their children. SNSK founded a limited liability company in 1989 to begin providing a wider range of services such as schools, libraries, community facilities, health care, and utilities. This allowed families to live year-round in the archipelago. The Norwegian government took over responsibilities for these services in 1993, which are now supported by a range of fees. While coal mining remains the largest industry in Svalbard, employing nearly 500 people and generating more than NOK 2 billion (approximately US$358 million) annually in revenue, tourism has become the second largest industry, employing more than 200 people directly. In 2008, more than 90,000 visitors came to Svalbard, and tourism now accounts for NOK 317 million (approximately US$57 million) in annual revenue. Svalbard took advantage of its unique environmental assets to develop an important second industry. While we may not have polar bears or glaciers in our towns, we may have similar opportunities to bring tourists—and their money—to visit the things that make our communities unique and interesting.

|

Published December 27, 2012 By Glenn Barnes

Quick trivia question—what is the northernmost town on earth?

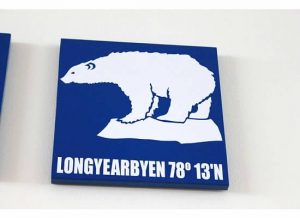

If you answered Santa’s Village, sorry. The man from the North Pole has had a busy week, but the actual answer is Longyearbyen in the Svalbard archipelago.

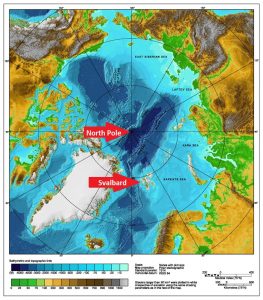

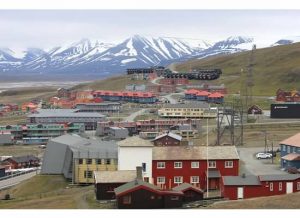

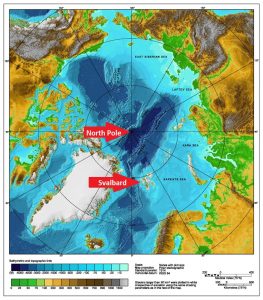

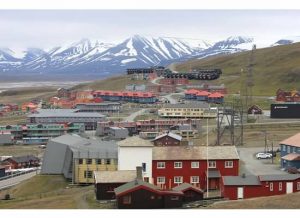

The Svalbard archipelago lies about 400 miles north of the northern coast of Norway, between 74 and 81 degrees north latitude, inside the Arctic Circle. Svalbard is administered by Norway and is led by a Governor. Longyearbyen (pronounced lung-yer-bin) is the largest town and seat of government for the islands.

The early visitors to Svalbard came in the 17th century for hunting, fishing, and whaling. Many polar expeditions were launched from Svalbard as well—Longyearbyen is roughly 800 miles from the North Pole. And coal mining became the islands’ largest industry in the early 1900s with major operations in Longyearbyen as well as the Soviet mining communities of Barentsburg and the now-abandoned Pyramiden.

Coal mining is still a major industry in Svalbard, led by Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK). So is scientific research. The world’s northernmost university center is in Longyearbyen, as is the Global Seed Vault. There is also a facility for the European Space Agency in Ny-Ålesund.

But for the past 20 years the driving economic force in Svalbard has been the expansion of the tourism industry. Climate patterns give Svalbard temperatures higher than other land masses at similar latitudes, which makes it more friendly for visitors. Its proximity to the North Pole is undoubtedly a draw. Svalbard has many of the world’s “northernmost” sites including the northernmost church, museum, hotel, and Thai restaurant. Summers feature 24 hours of daylight, while the polar night skies are lit up by Aurora Borealis. Svalbard is far enough north that there are no trees, and reindeer literally wander the streets of the towns. Sixty-five percent of the archipelago is protected land, and 60 percent of the islands are covered in glaciers.

Perhaps the most iconic draw of Svalbard, though, is the polar bear. About one-sixth of the world’s polar bears live in Svalbard—they actually outnumber the people. While typically the only sightings of the bears in town are on the tourist signs, anyone leaving town boundaries is required to carry a registered firearm for protection.

The decision to expand tourism in Svalbard, which was laid out in 1990-1991’s Report No. 50, emphasized the need to develop tourism at a scale that would not threaten the area’s distinctive wilderness. Rather, that natural environment would become the focus of the tourism but with limits on the number of visitors, types of activities, and other potential stresses. Today, virtually all of the activities for visitors to Svalbard involve eco-tourism—boat trips through the fjords, dogsledding and snowmobile trips across the ice caps, hiking on glaciers, kayaking, and other outdoor activities.

The expansion of tourism also presented public administration challenges for Svalbard. Up until the late 1980s, Longyearbyen operated as a company town, with SNSK providing minimal services to its employees. The expansion of tourism also required the expansion of basic government services—hotels needed reliable heat and hot water, while employees needed schools for their children. SNSK founded a limited liability company in 1989 to begin providing a wider range of services such as schools, libraries, community facilities, health care, and utilities. This allowed families to live year-round in the archipelago. The Norwegian government took over responsibilities for these services in 1993, which are now supported by a range of fees.

While coal mining remains the largest industry in Svalbard, employing nearly 500 people and generating more than NOK 2 billion (approximately US$358 million) annually in revenue, tourism has become the second largest industry, employing more than 200 people directly. In 2008, more than 90,000 visitors came to Svalbard, and tourism now accounts for NOK 317 million (approximately US$57 million) in annual revenue.

Svalbard took advantage of its unique environmental assets to develop an important second industry. While we may not have polar bears or glaciers in our towns, we may have similar opportunities to bring tourists—and their money—to visit the things that make our communities unique and interesting.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.