|

|

Student Corner: How a Mezzanine Loan Can Reduce Equity Requirements, Boost Returns, and Attract Investment to a Redevelopment ProjectBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished March 23, 2017

Market analysis has identified gaps in the local market that could be successful as part of a rehabilitation project. A specific retail gap analysis found several potential retail uses that were not currently captured in the market, including a full-service restaurant. Additionally, though Milliganton has many affordable multifamily establishments in town, there are virtually no market-rate apartments. As a unique product in the residential market, loft-style apartments on the Parker Building’s second floor could be marketed to those working in the town’s many healthcare and education jobs. The local community college has also expressed interest in leasing classroom and/or office space on the site. A preliminary development budget for the building estimates that redeveloping the building into a mix of ground-floor commercial space (retail or office) and second-floor residential loft units would cost $1.2 million. The Parker Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and therefore could be eligible to receive federal and state tax credits for historic rehabilitation. Since historic rehabilitation projects typically have high construction costs, these tax credits, which essentially reduce a project’s equity requirements by providing tax credits equal to 40 percent of certain rehabilitation expenses, help to make projects more financially feasible for investors. North Carolina’s historic tax credit program was recently renewed–after a brief lapse—with new rules for 2015. Based on the project’s likely “qualified rehabilitation expenses,” historic tax credit equity could contribute more than a quarter of the total $1.2 million development cost. Typically, the rest of the development costs would then have to be funded through debt and equity sources. Given the low market rents that the project would probably support, a traditional bank might only be willing to loan $350,000 (or 29 percent of project costs) based on a potential income valuation of the property. This would result in an cash requirement of $462,000, or 38 percent of project costs, with an equity multiple of 2 (in this scenario, an additional 8 percent of project costs are provided as equity in the form of a deferred developer fee). An equity multiple of 2 simply means that investors should expect to receive twice as much cash as they originally invested. This would not be an attractive investment for most investors: the share of cash to total project costs is much too high and the returns are not attractive for a project in a smaller market like Milliganton. Here’s a breakdown of this base case scenario: Yet by providing a mezzanine loan, the Town or another public institution could help make this investment more attractive by simultaneously decreasing the equity requirement and increasing returns. A mezzanine loan is subordinated debt with a higher interest-rate, meaning that the Town’s loan would only be repaid after the project first repaid the loan from the bank (a higher-risk position for the local government). In the case of Milliganton’s Parker Building, a $150,000 interest-only mezzanine loan would increase the project’s leverage. By increasing leverage, or the amount of borrowed funds, the developer does not have to raise as much cash to fund the project. This is a good thing for investors who want to limit the amount of their own cash in a project and raise the equity multiple while maintaining a reasonable debt service coverage ratio, or income to debt ratio. In addition, the local government would earn an annual return from the project in the form of interest and would see its initial investment paid back upon sale of the building in year 6, which would net the Town $54,000. Here’s how the case changes with the mezzanine loan: The use of mezzanine financing is not appropriate in all scenarios. It shifts risk onto the mezzanine lender, and therefore typically entails interest rates significantly higher than primary loans. Yet in certain cases, a local government or other lender that seeks to make a redevelopment project successful can do so through a carefully-designed mezzanine loan. For another example of how a local government can make a redevelopment project possible through the use of a mezzanine loan, take a look at this past blog post. A graduate student team performed the financial feasibility analysis in this post and presented it to local government officials as part of their graduate degree course work. Does your local government have a project like this for a graduate student team? If so, complete the webform here. Tim J. Quinn is a former Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative (DFI) and a graduate of the Master of City and Regional Planning program at UNC Chapel Hill. Andrew Trump, DFI Project Manager, and Omar Kashef, current Community Revitalization Fellow with DFI, also contributed content to this post. |

Published March 23, 2017 By CED Program Interns & Students

The Parker Building is a two-story, 8,000-SF brick building in downtown Milliganton, NC. The building is subdivided into two small retail tenant spaces, but for the most part it is an empty shell. Despite having been mostly vacant for the last several decades, the building is in good shape. A recent roof repair and functional heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning have kept the building from falling into disrepair.

The Parker Building is a two-story, 8,000-SF brick building in downtown Milliganton, NC. The building is subdivided into two small retail tenant spaces, but for the most part it is an empty shell. Despite having been mostly vacant for the last several decades, the building is in good shape. A recent roof repair and functional heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning have kept the building from falling into disrepair.

Market analysis has identified gaps in the local market that could be successful as part of a rehabilitation project. A specific retail gap analysis found several potential retail uses that were not currently captured in the market, including a full-service restaurant. Additionally, though Milliganton has many affordable multifamily establishments in town, there are virtually no market-rate apartments. As a unique product in the residential market, loft-style apartments on the Parker Building’s second floor could be marketed to those working in the town’s many healthcare and education jobs. The local community college has also expressed interest in leasing classroom and/or office space on the site.

A preliminary development budget for the building estimates that redeveloping the building into a mix of ground-floor commercial space (retail or office) and second-floor residential loft units would cost $1.2 million.

The Parker Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and therefore could be eligible to receive federal and state tax credits for historic rehabilitation. Since historic rehabilitation projects typically have high construction costs, these tax credits, which essentially reduce a project’s equity requirements by providing tax credits equal to 40 percent of certain rehabilitation expenses, help to make projects more financially feasible for investors. North Carolina’s historic tax credit program was recently renewed–after a brief lapse—with new rules for 2015.

Based on the project’s likely “qualified rehabilitation expenses,” historic tax credit equity could contribute more than a quarter of the total $1.2 million development cost.

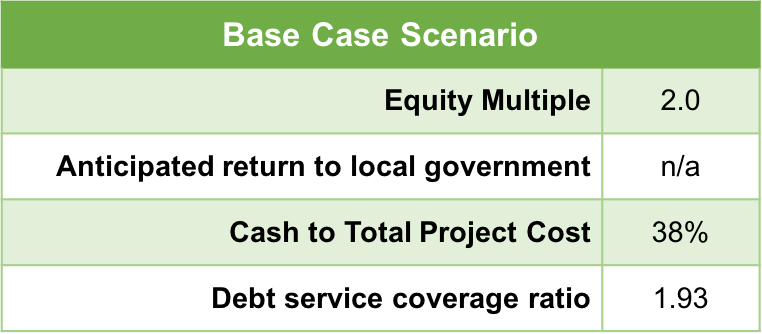

Typically, the rest of the development costs would then have to be funded through debt and equity sources. Given the low market rents that the project would probably support, a traditional bank might only be willing to loan $350,000 (or 29 percent of project costs) based on a potential income valuation of the property. This would result in an cash requirement of $462,000, or 38 percent of project costs, with an equity multiple of 2 (in this scenario, an additional 8 percent of project costs are provided as equity in the form of a deferred developer fee). An equity multiple of 2 simply means that investors should expect to receive twice as much cash as they originally invested. This would not be an attractive investment for most investors: the share of cash to total project costs is much too high and the returns are not attractive for a project in a smaller market like Milliganton. Here’s a breakdown of this base case scenario:

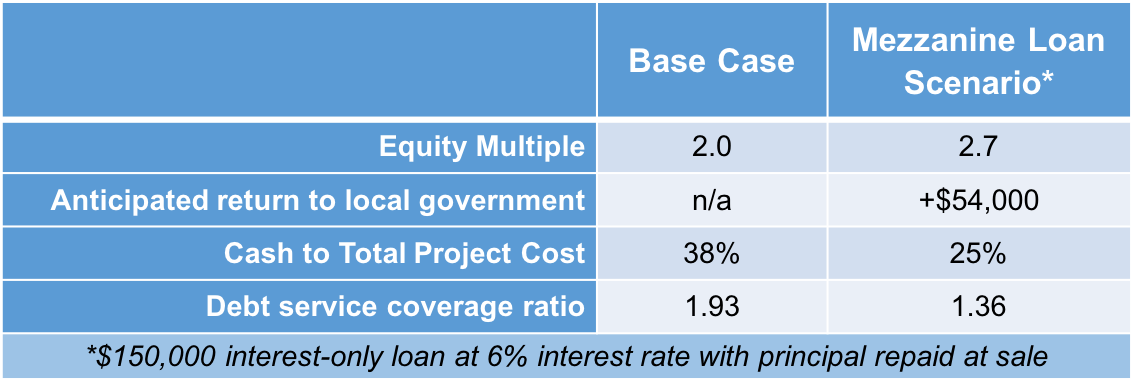

Yet by providing a mezzanine loan, the Town or another public institution could help make this investment more attractive by simultaneously decreasing the equity requirement and increasing returns. A mezzanine loan is subordinated debt with a higher interest-rate, meaning that the Town’s loan would only be repaid after the project first repaid the loan from the bank (a higher-risk position for the local government).

In the case of Milliganton’s Parker Building, a $150,000 interest-only mezzanine loan would increase the project’s leverage. By increasing leverage, or the amount of borrowed funds, the developer does not have to raise as much cash to fund the project. This is a good thing for investors who want to limit the amount of their own cash in a project and raise the equity multiple while maintaining a reasonable debt service coverage ratio, or income to debt ratio. In addition, the local government would earn an annual return from the project in the form of interest and would see its initial investment paid back upon sale of the building in year 6, which would net the Town $54,000. Here’s how the case changes with the mezzanine loan:

The use of mezzanine financing is not appropriate in all scenarios. It shifts risk onto the mezzanine lender, and therefore typically entails interest rates significantly higher than primary loans. Yet in certain cases, a local government or other lender that seeks to make a redevelopment project successful can do so through a carefully-designed mezzanine loan.

For another example of how a local government can make a redevelopment project possible through the use of a mezzanine loan, take a look at this past blog post. A graduate student team performed the financial feasibility analysis in this post and presented it to local government officials as part of their graduate degree course work. Does your local government have a project like this for a graduate student team? If so, complete the webform here.

Tim J. Quinn is a former Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative (DFI) and a graduate of the Master of City and Regional Planning program at UNC Chapel Hill. Andrew Trump, DFI Project Manager, and Omar Kashef, current Community Revitalization Fellow with DFI, also contributed content to this post.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.