|

|

Sale of Historic Structures by NC Local Governments for RedevelopmentBy Tyler MulliganPublished December 16, 2014

The town recognizes that it needs to market the building more actively—and that it may need the help of experts. “Old Mills R Us,” a regional historic preservation nonprofit with a mission to preserve historic mill buildings, has a proposal for the town:

Can the town enter into this transaction with OMRU? Short answer: not on these terms. This post explains why and suggests some alternatives. General Background on Disposal of Local Government PropertyWe start with the general rule that, unless an exception is authorized by statute, North Carolina local governments are required to dispose of real property through competitive bidding procedures. Three procedures are available: sealed bid (G.S. 160A-268), upset bid (G.S. 160A-269), or public auction (G.S. 160A-270). These bidding procedures are fair to the public in the sense that anyone with the means can submit a bid—there are no back-room deals. The procedures are assumed to be favorable to the government because theoretically, the process should yield the highest possible price. The law assumes that price is the most important factor to local governments; indeed, case law generally prohibits local governments from placing conditions on conveyances of property that will depress the price that a buyer would pay (Puett v. Gaston County). However, from time to time, compelling and overriding public interests have led the General Assembly to enact exceptions to the competitive bidding requirement. Historic preservation is one of those exceptions. In such instances, the statutes permit local governments to engage in a private sale (as described in G.S. 160A-267)—that is, the local government may select the buyer of its choice without following a public bidding process and, when allowed by statute, may impose covenants and restrictions on the conveyance. The authority to convey property by private sale does not mean that the property can be given away for nothing. Rather, the property is to be sold at or near fair market value, because gifts of public money or assets to private persons are not permitted under Article 1, Section 32 of the North Carolina Constitution (for further legal analysis of that constitutional provision, see a blog post on the topic by faculty member Frayda Bluestein). Note, however, that when a statute permits a local government to impose covenants or restrictions on a conveyance, the law recognizes that the property’s value may be impaired by those restrictions and appraisers may take the restrictions into account when calculating fair market value. In rare instances, the statutes may even permit a local government to sell property for less than full fair market value, provided some other allowable form of consideration or “payment” is provided. For example, whenever a local government is permitted to appropriate funds to a nonprofit entity for carrying out a public purpose, it may also convey property to that entity “in lieu of or in addition to the appropriation of funds.” In other words, the local government may make a conveyance of property for less than fair market value just as it would make an appropriation through its general fund. In that case, the conveyance must be subject to covenants ensuring that the property will be “put to a public use by the recipient entity” (G.S. 160A-279). The next section examines how and whether these exceptions apply to the sale of historic property. Private Sale of Historic PropertyThere is specific statutory authority for the sale of historic property. G.S. 160A-266(b) authorizes local governments to convey historic property by private sale—meaning, the unit gets to pick its buyer and impose covenants and restrictions to preserve the historic property. Notably, the local government may use this private sale authority only for conveyance to a nonprofit or trust whose purpose is to conserve or preserve historic property, and the deed must be subject to a conservation agreement as defined by G.S. 121-35. The preservation nonprofit, after it purchases the property under G.S. 160A-266, is permitted to turn around and sell the property subject to covenants that promote the preservation or conservation of the historic property. In addition, if the local government has established a statutory historic preservation commission (G.S. 160A-400.7), then the commission actually possesses greater authority than the governing board. A governing board is limited to using private sale only when selling to a nonprofit with a historic preservation mission, but a statutory commission is empowered to purchase historic properties and then convey at private sale to any party, subject to covenants that will “secure appropriate rights of public access and promote the preservation of the property.” It is not surprising that the General Assembly granted more authority to statutory commissions, because, after all, a majority of the members of a commission must have special interest or expertise in fields related to historic preservation (G.S. 160A-400.7), so presumably they will act knowledgably when selling historic assets without the aid of a historic preservation nonprofit. Let’s return to our scenario involving OMRU and the historic mill property. OMRU is a nonprofit with a historic preservation mission, so the private sale procedures of G.S. 160A-266 are available. Accordingly, the local government may sell the historic mill to OMRU through private sale, provided a conservation agreement is placed in the deed. If the local government has formed a historic preservation commission, then that commission could exercise essentially the same powers and sell the property to OMRU—and it could even sell the property directly to a private developer—subject to preservation covenants and restrictions (G.S. 160A-400.8(3)). However, there is a still a wrinkle to resolve. OMRU wants to purchase the property for only one dollar—far below the fair market value. Is such a low price permissible? Consideration to be Paid in Sale of Historic PropertyRecall the constitutional prohibition against making gifts of public assets that was mentioned previously. In a sale of public property, the buyer must either participate in a public bidding process (where the winning bid is assumed to be fair market value) or, if private sale is authorized, pay fair market value. There are only two ways that the property could be sold to OMRU for less than fair market value:

Accordingly, in our scenario, it appears that the local government cannot reduce the sale price below fair market value. This conclusion makes even more sense when placed in context with other, similar authorities. The most similar situation involves local government authority to convey property for redevelopment. When a local government employs the vast powers of a redevelopment commission (as described here), private sale is not permitted at all—competitive bidding procedures must be used. A set of alternative redevelopment statutes, G.S. 160A-457(3) (cities) and G.S. 153A-377(3) (counties), may be used to convey property for redevelopment when a redevelopment commission is not available. Under those statutes as well, competitive bidding procedures must be used. Private sale is available only in very limited circumstances when cities are following a community development plan for the benefit of low and moderate income persons, and even in that case, the property must be sold for the appraised value of the property. Likewise, in the economic development context, G.S. 158-7.1(d) permits local governments to convey property by private sale to a business that will employ workers at the site, but the sale price must be no less than the “fair market value” (note there is an exception under G.S. 158-7.1(d2) for competitive economic development projects when a substantial number of jobs and new tax revenue will result). Reading these statutes together, and in the absence of specific statutory authority allowing local governments to reduce the price of historic property, it seems clear that the authority to convey historic properties for redevelopment does not include the power to accept payment of less than fair market value. No discount on sale price—but alternatives?Having determined that the local government must sell the property to OMRU for fair market value (after accounting for the effect of any historic preservation restrictions)—not for one dollar as OMRU proposed—are there lawful alternatives that might compensate OMRU for its assistance with selling the mill property? There are a few options, but they are not as lucrative for OMRU as its original proposal. One possibility is for the local government to purchase a preservation easement on the property and to pay a fee to OMRU for assisting with monitoring and compliance (a local historic preservation commission is empowered to purchase easements and manage them pursuant to G.S. 160A-400.8(3)). Another possibility is that the unit could pay OMRU a customary broker’s fee for marketing the property and for identifying a high-quality developer to buy the property. Options without OMRU in the dealKeep in mind, too, that there are other options that don’t involve OMRU at all. For example, G.S. 160A-400.8(3) empowers a historic preservation commission to restore, preserve, hold, and manage historic properties, so a commission could rehabilitate the property on its own. In addition, local governments, regardless of whether they have an active statutory preservation commission, possess authority to construct and lease out commercial space for economic development pursuant to G.S. 158-7.1(b)(4), or, if the property is well-suited for residential units, to construct and manage housing for low- and moderate-income persons (G.S. Chapter 157, G.S. 160A-456, G.S. 153A-376). Finally, the local government could even engage a developer directly for the rehabilitation as part of a public-private partnership for construction (P3), provided the local government intends to include a public facility (such as public staff offices) as part of the project. For an example of a historic mill redevelopment accomplished through a P3 led by a North Carolina town, see this post on the School’s Community and Economic Development blog. See this post for more information about local government legal authority to enter into a P3 for construction of public facilities. |

Published December 16, 2014 By Tyler Mulligan

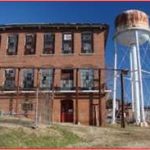

Almost ten years ago, in the town of Bushwood, North Carolina, the “generous” owner of the historic textile mill building just off Main Street donated the property to the town (it was difficult to maintain and the owner didn’t want to pay property taxes on it any more). The town accepted the property, hoping that it would be able to find a new private owner who would redevelop the property and retain the historic character of the building. Some potential buyers have kicked the tires on the building, but no one has made an offer. Due to the value of the land and the excellent location of the parcel, the property appraises for $300,000.

Almost ten years ago, in the town of Bushwood, North Carolina, the “generous” owner of the historic textile mill building just off Main Street donated the property to the town (it was difficult to maintain and the owner didn’t want to pay property taxes on it any more). The town accepted the property, hoping that it would be able to find a new private owner who would redevelop the property and retain the historic character of the building. Some potential buyers have kicked the tires on the building, but no one has made an offer. Due to the value of the land and the excellent location of the parcel, the property appraises for $300,000.

The town recognizes that it needs to market the building more actively—and that it may need the help of experts. “Old Mills R Us,” a regional historic preservation nonprofit with a mission to preserve historic mill buildings, has a proposal for the town:

- The town will sell the mill to the nonprofit for one dollar.

- Old Mills R Us (OMRU) will market the property and sell the mill to a private developer who will redevelop the property while retaining the historic features.

- Rather than charging a broker fee, OMRU will simply keep the proceeds from the sale at whatever price OMRU can get.

Can the town enter into this transaction with OMRU? Short answer: not on these terms. This post explains why and suggests some alternatives.

General Background on Disposal of Local Government Property

We start with the general rule that, unless an exception is authorized by statute, North Carolina local governments are required to dispose of real property through competitive bidding procedures. Three procedures are available: sealed bid (G.S. 160A-268), upset bid (G.S. 160A-269), or public auction (G.S. 160A-270). These bidding procedures are fair to the public in the sense that anyone with the means can submit a bid—there are no back-room deals. The procedures are assumed to be favorable to the government because theoretically, the process should yield the highest possible price. The law assumes that price is the most important factor to local governments; indeed, case law generally prohibits local governments from placing conditions on conveyances of property that will depress the price that a buyer would pay (Puett v. Gaston County).

However, from time to time, compelling and overriding public interests have led the General Assembly to enact exceptions to the competitive bidding requirement. Historic preservation is one of those exceptions. In such instances, the statutes permit local governments to engage in a private sale (as described in G.S. 160A-267)—that is, the local government may select the buyer of its choice without following a public bidding process and, when allowed by statute, may impose covenants and restrictions on the conveyance.

The authority to convey property by private sale does not mean that the property can be given away for nothing. Rather, the property is to be sold at or near fair market value, because gifts of public money or assets to private persons are not permitted under Article 1, Section 32 of the North Carolina Constitution (for further legal analysis of that constitutional provision, see a blog post on the topic by faculty member Frayda Bluestein). Note, however, that when a statute permits a local government to impose covenants or restrictions on a conveyance, the law recognizes that the property’s value may be impaired by those restrictions and appraisers may take the restrictions into account when calculating fair market value.

In rare instances, the statutes may even permit a local government to sell property for less than full fair market value, provided some other allowable form of consideration or “payment” is provided. For example, whenever a local government is permitted to appropriate funds to a nonprofit entity for carrying out a public purpose, it may also convey property to that entity “in lieu of or in addition to the appropriation of funds.” In other words, the local government may make a conveyance of property for less than fair market value just as it would make an appropriation through its general fund. In that case, the conveyance must be subject to covenants ensuring that the property will be “put to a public use by the recipient entity” (G.S. 160A-279).

The next section examines how and whether these exceptions apply to the sale of historic property.

Private Sale of Historic Property

There is specific statutory authority for the sale of historic property. G.S. 160A-266(b) authorizes local governments to convey historic property by private sale—meaning, the unit gets to pick its buyer and impose covenants and restrictions to preserve the historic property. Notably, the local government may use this private sale authority only for conveyance to a nonprofit or trust whose purpose is to conserve or preserve historic property, and the deed must be subject to a conservation agreement as defined by G.S. 121-35. The preservation nonprofit, after it purchases the property under G.S. 160A-266, is permitted to turn around and sell the property subject to covenants that promote the preservation or conservation of the historic property.

In addition, if the local government has established a statutory historic preservation commission (G.S. 160A-400.7), then the commission actually possesses greater authority than the governing board. A governing board is limited to using private sale only when selling to a nonprofit with a historic preservation mission, but a statutory commission is empowered to purchase historic properties and then convey at private sale to any party, subject to covenants that will “secure appropriate rights of public access and promote the preservation of the property.” It is not surprising that the General Assembly granted more authority to statutory commissions, because, after all, a majority of the members of a commission must have special interest or expertise in fields related to historic preservation (G.S. 160A-400.7), so presumably they will act knowledgably when selling historic assets without the aid of a historic preservation nonprofit.

Let’s return to our scenario involving OMRU and the historic mill property. OMRU is a nonprofit with a historic preservation mission, so the private sale procedures of G.S. 160A-266 are available. Accordingly, the local government may sell the historic mill to OMRU through private sale, provided a conservation agreement is placed in the deed. If the local government has formed a historic preservation commission, then that commission could exercise essentially the same powers and sell the property to OMRU—and it could even sell the property directly to a private developer—subject to preservation covenants and restrictions (G.S. 160A-400.8(3)).

However, there is a still a wrinkle to resolve. OMRU wants to purchase the property for only one dollar—far below the fair market value. Is such a low price permissible?

Consideration to be Paid in Sale of Historic Property

Recall the constitutional prohibition against making gifts of public assets that was mentioned previously. In a sale of public property, the buyer must either participate in a public bidding process (where the winning bid is assumed to be fair market value) or, if private sale is authorized, pay fair market value. There are only two ways that the property could be sold to OMRU for less than fair market value:

- Fair market value is reduced as a result of the covenants and restrictions imposed pursuant to G.S. 160A-266(b). The value of commercial property is typically reflective of the income potential of the property. If the income potential is high, then the value of the property will be high. When a property is subject to historic preservation restrictions that limit how the property may be redeveloped, the additional costs and lost revenues associated with complying with the restrictions could reduce the income potential of the property and therefore reduce its value. However, the additional costs associated with historic preservation are mitigated by the use of long-term debt, historic tax credits and other subsidies, and rent premiums that redeveloped historic structures command in the market. As long as there is adequate market demand for space in a redeveloped historic structure, it is essentially inconceivable that the value of the property would be reduced to one dollar by historic preservation covenants. The School of Government’s Development Finance Initiative (DFI) can help local governments assess the market potential for redeveloped historic properties, and a property appraiser could assess the value of the property after factoring in the effect of historic preservation covenants.

- OMRU agrees to put the property to public use and the local government is permitted to appropriate funds to OMRU for that purpose pursuant to G.S. 160A-279. A private sale pursuant to G.S. 160A-279 is not related to the historic character of the property. As mentioned earlier, G.S. 160A-279 allows conveyance by private sale provided there are covenants and restrictions to assure the property is put to a public use by the recipient entity (OMRU in this case). A public use might include using the space as, for example, a museum, or police sub-station. OMRU could certainly promise to put the property to a public use, but in this case, OMRU intends to sell the property to a for-profit private developer (G.S. 160A-279 specifically prohibits conveyances to a for-profit corporation), and the intended use is not a public use. Additionally, in order to avail itself of the private sale procedures of G.S. 160A-279, the local government must be authorized to appropriate funds to OMRU. Local governments are permitted to establish statutory historic preservation commissions and to appropriate funds to those commissions (G.S. 160A-400.12), but OMRU is not such a commission and therefore it is questionable whether a local government possesses authority to appropriate funds directly to OMRU.

Accordingly, in our scenario, it appears that the local government cannot reduce the sale price below fair market value.

This conclusion makes even more sense when placed in context with other, similar authorities. The most similar situation involves local government authority to convey property for redevelopment. When a local government employs the vast powers of a redevelopment commission (as described here), private sale is not permitted at all—competitive bidding procedures must be used. A set of alternative redevelopment statutes, G.S. 160A-457(3) (cities) and G.S. 153A-377(3) (counties), may be used to convey property for redevelopment when a redevelopment commission is not available. Under those statutes as well, competitive bidding procedures must be used. Private sale is available only in very limited circumstances when cities are following a community development plan for the benefit of low and moderate income persons, and even in that case, the property must be sold for the appraised value of the property. Likewise, in the economic development context, G.S. 158-7.1(d) permits local governments to convey property by private sale to a business that will employ workers at the site, but the sale price must be no less than the “fair market value” (note there is an exception under G.S. 158-7.1(d2) for competitive economic development projects when a substantial number of jobs and new tax revenue will result). Reading these statutes together, and in the absence of specific statutory authority allowing local governments to reduce the price of historic property, it seems clear that the authority to convey historic properties for redevelopment does not include the power to accept payment of less than fair market value.

No discount on sale price—but alternatives?

Having determined that the local government must sell the property to OMRU for fair market value (after accounting for the effect of any historic preservation restrictions)—not for one dollar as OMRU proposed—are there lawful alternatives that might compensate OMRU for its assistance with selling the mill property? There are a few options, but they are not as lucrative for OMRU as its original proposal. One possibility is for the local government to purchase a preservation easement on the property and to pay a fee to OMRU for assisting with monitoring and compliance (a local historic preservation commission is empowered to purchase easements and manage them pursuant to G.S. 160A-400.8(3)). Another possibility is that the unit could pay OMRU a customary broker’s fee for marketing the property and for identifying a high-quality developer to buy the property.

Options without OMRU in the deal

Keep in mind, too, that there are other options that don’t involve OMRU at all. For example, G.S. 160A-400.8(3) empowers a historic preservation commission to restore, preserve, hold, and manage historic properties, so a commission could rehabilitate the property on its own. In addition, local governments, regardless of whether they have an active statutory preservation commission, possess authority to construct and lease out commercial space for economic development pursuant to G.S. 158-7.1(b)(4), or, if the property is well-suited for residential units, to construct and manage housing for low- and moderate-income persons (G.S. Chapter 157, G.S. 160A-456, G.S. 153A-376). Finally, the local government could even engage a developer directly for the rehabilitation as part of a public-private partnership for construction (P3), provided the local government intends to include a public facility (such as public staff offices) as part of the project. For an example of a historic mill redevelopment accomplished through a P3 led by a North Carolina town, see this post on the School’s Community and Economic Development blog. See this post for more information about local government legal authority to enter into a P3 for construction of public facilities.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.