|

|

Student Corner: Strategies for Creating Mixed-Income NeighborhoodsBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished August 6, 2019

Throughout the process, the topic of mixed-income development was reoccurring. What exactly does mixed-income mean? And how can it be administered and achieved? For Durham, given current state-level regulations, mixed-income ultimately came to mean a diversity of income across the broader neighborhood context. While incomes will be mixed within the larger development site, the buildings themselves will house either market-rate or income-restricted affordable housing. Importantly, using newly implemented income-averaging set asides (CED post forthcoming), the affordable side of the development will serve incomes between 20% and 80% of the Area Median Income (AMI). This extension of the income spectrum not only deepens the project’s affordability, it introduces a wider range of incomes to the site. When completed, the two developments will together serve households earning between 20% and 140% AMI. Given current regulations, DFI and Durham County’s plan has achieved the most diversity of incomes possible. Nevertheless, questions around mixed-income and income-diversity remain. The purpose of this post is to first discuss the theories of mixed-income neighborhoods and residential developments before briefly discussing implementation strategies through state-administered Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) programs. Evidence and Theories of Income DiversityMixed-income neighborhood strategies have been a part of housing and neighborhood policy narratives since at least the 1960s. Further developed in the housing literature in the 1980s and 90s, the general arguments behind these policy proposals posit first that concentrated poverty perpetuates a cycle of individual adversity and neighborhood disinvestment. Poorer neighborhoods have observably lower access to amenities and services, and individuals living in these neighborhoods, both children and adults, are far less able to improve their economic wellbeing. The attraction of higher income households through private, market-rate developments, then, is seen as a potential solution to poverty concentration. By breaking down the spatial segregation of household incomes, advocates theorize that neighborhood vitality in disinvested areas will improve while the ability of individuals to improve their economic situations will expand. Specifically, these changes are thought to occur due to the increased interaction and subsequent social capital between individuals as well as the increased private investment and expanded access to amenities and services. Despite its popularity in the literature, evidence of improved economic outcomes in mixed-income communities and developments appears to be limited. Outlined by Levy, McDade, and Bertumen, a series of studies in the 1990s and 2000s showed individuals that moved to income-diverse neighborhoods do not necessarily interact with individuals with higher incomes and see few gains in income and employment. Further research, however, points to evidence of improved neighborhood conditions, such as housing quality and access to amenities and services, as well as improved health and educational outcomes for low-income households. Overall, while income diversity appears to have minimal effects on the economic outcomes of low-income households, income desegregation does appear to affect social and community factors. Importantly, Levy, McDade, and Bertumen conclude their article with a recommendation to improve the economic outcomes of low-income residents in mixed-income neighborhoods. By designing intentional spaces of interaction, social ties and capital would likely be strengthened. That is, positive economic outcomes are more likely when income-diverse areas are designed with a community perspective. By incorporating mixed-income housing into the same development, this design is more easily managed, and the important social interactions are potentially more likely. One potential tool to promote income-diverse developments is the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Private and non-profit developers can apply for tax credit funding to offset a housing development’s equity requirements. In North Carolina, the distribution process of these credits is managed by the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency (NCHFA). The rules of this process are outline in the Qualified Application Plan (QAP), which is updated by the NCHFA on an annual basis. (For more information about the LIHTC program as a tool for community economic development, consult previous posts here, here, here, and here.) Mixed-Income LIHTC Developments Across the United StatesUsing data available from HUD, it is possible to identify and map mixed-income LIHTC developments across the country. The map and table below show the concentration of these projects by state since 2010. Individual projects with fewer than 10 non-LIHTC units and states with fewer than 5 mixed-income developments were filtered from the analysis. States with at least 10 mixed-income developments are reported in the adjacent table. LIHTC Projects Constructed Since 2010 with Mixed-Income Components

Overall, New York and Wisconsin significantly outperform all other states, while regional concentrations appear in the Northeast, Midwest, and West. For Wisconsin and New York, these higher concentrations are not by chance, as mixed-income developments are prioritized under each state’s Qualified Application Plan.

Importantly, unlike some other states, the NCHFA QAP does not currently prioritize the inclusion of market rate units in LIHTC developments. Under current guidelines, developments must be entirely composed of income-restricted affordable units to maximize their award potential. By following the examples of other states and prioritizing mixed-income within developments, North Carolina might more efficiently leverage the economic benefits associated with income diversity. While affordable housing projects like that in Durham County serve the most diverse array of incomes currently possible, changes to the QAP guidelines could elevate their potential economic impacts while encouraging income-diverse development across the state. Matthew Hutton is a dual Master’s degree candidate in the Master of Public Administration and the Master of City & Regional Planning programs at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is also a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. |

Published August 6, 2019 By CED Program Interns & Students

Durham County hired the Development Finance Initiative (DFI) in 2017 to help redevelop two county-owned parcels in downtown. Though currently serving as surface parking for county employees, the two sites are located adjacent to recent high-end residential development, government and institutional services, and subsidized public housing. County and community leaders recognized the strong potential of these sites to transform the area’s character and hired DFI to help develop a plan for a mixed-income residential development. After 18 months of intensive analysis and community engagement, the County—with the help of DFI—selected a development partner in early July 2019.

Durham County hired the Development Finance Initiative (DFI) in 2017 to help redevelop two county-owned parcels in downtown. Though currently serving as surface parking for county employees, the two sites are located adjacent to recent high-end residential development, government and institutional services, and subsidized public housing. County and community leaders recognized the strong potential of these sites to transform the area’s character and hired DFI to help develop a plan for a mixed-income residential development. After 18 months of intensive analysis and community engagement, the County—with the help of DFI—selected a development partner in early July 2019.

Throughout the process, the topic of mixed-income development was reoccurring. What exactly does mixed-income mean? And how can it be administered and achieved? For Durham, given current state-level regulations, mixed-income ultimately came to mean a diversity of income across the broader neighborhood context. While incomes will be mixed within the larger development site, the buildings themselves will house either market-rate or income-restricted affordable housing.

Importantly, using newly implemented income-averaging set asides (CED post forthcoming), the affordable side of the development will serve incomes between 20% and 80% of the Area Median Income (AMI). This extension of the income spectrum not only deepens the project’s affordability, it introduces a wider range of incomes to the site. When completed, the two developments will together serve households earning between 20% and 140% AMI.

Given current regulations, DFI and Durham County’s plan has achieved the most diversity of incomes possible. Nevertheless, questions around mixed-income and income-diversity remain. The purpose of this post is to first discuss the theories of mixed-income neighborhoods and residential developments before briefly discussing implementation strategies through state-administered Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) programs.

Evidence and Theories of Income Diversity

Mixed-income neighborhood strategies have been a part of housing and neighborhood policy narratives since at least the 1960s. Further developed in the housing literature in the 1980s and 90s, the general arguments behind these policy proposals posit first that concentrated poverty perpetuates a cycle of individual adversity and neighborhood disinvestment. Poorer neighborhoods have observably lower access to amenities and services, and individuals living in these neighborhoods, both children and adults, are far less able to improve their economic wellbeing.

The attraction of higher income households through private, market-rate developments, then, is seen as a potential solution to poverty concentration. By breaking down the spatial segregation of household incomes, advocates theorize that neighborhood vitality in disinvested areas will improve while the ability of individuals to improve their economic situations will expand. Specifically, these changes are thought to occur due to the increased interaction and subsequent social capital between individuals as well as the increased private investment and expanded access to amenities and services.

Despite its popularity in the literature, evidence of improved economic outcomes in mixed-income communities and developments appears to be limited. Outlined by Levy, McDade, and Bertumen, a series of studies in the 1990s and 2000s showed individuals that moved to income-diverse neighborhoods do not necessarily interact with individuals with higher incomes and see few gains in income and employment. Further research, however, points to evidence of improved neighborhood conditions, such as housing quality and access to amenities and services, as well as improved health and educational outcomes for low-income households. Overall, while income diversity appears to have minimal effects on the economic outcomes of low-income households, income desegregation does appear to affect social and community factors.

Importantly, Levy, McDade, and Bertumen conclude their article with a recommendation to improve the economic outcomes of low-income residents in mixed-income neighborhoods. By designing intentional spaces of interaction, social ties and capital would likely be strengthened. That is, positive economic outcomes are more likely when income-diverse areas are designed with a community perspective. By incorporating mixed-income housing into the same development, this design is more easily managed, and the important social interactions are potentially more likely.

One potential tool to promote income-diverse developments is the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Private and non-profit developers can apply for tax credit funding to offset a housing development’s equity requirements. In North Carolina, the distribution process of these credits is managed by the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency (NCHFA). The rules of this process are outline in the Qualified Application Plan (QAP), which is updated by the NCHFA on an annual basis. (For more information about the LIHTC program as a tool for community economic development, consult previous posts here, here, here, and here.)

Mixed-Income LIHTC Developments Across the United States

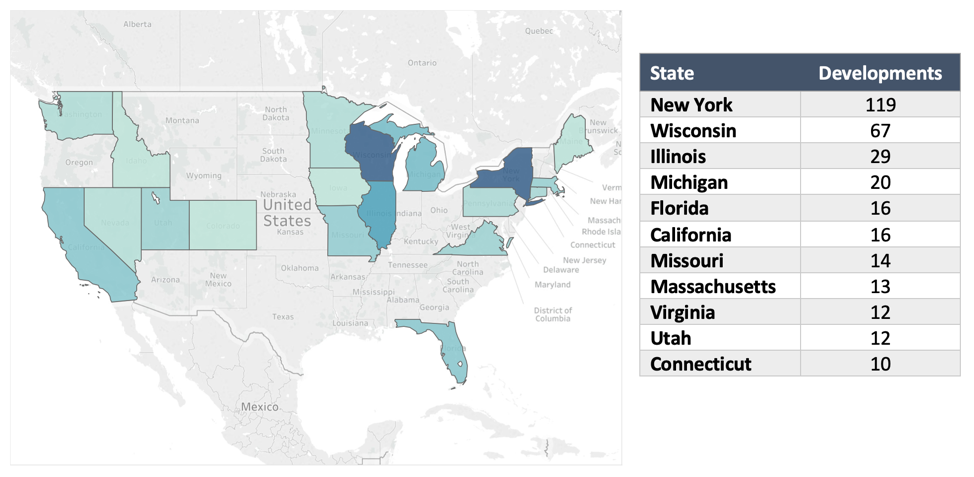

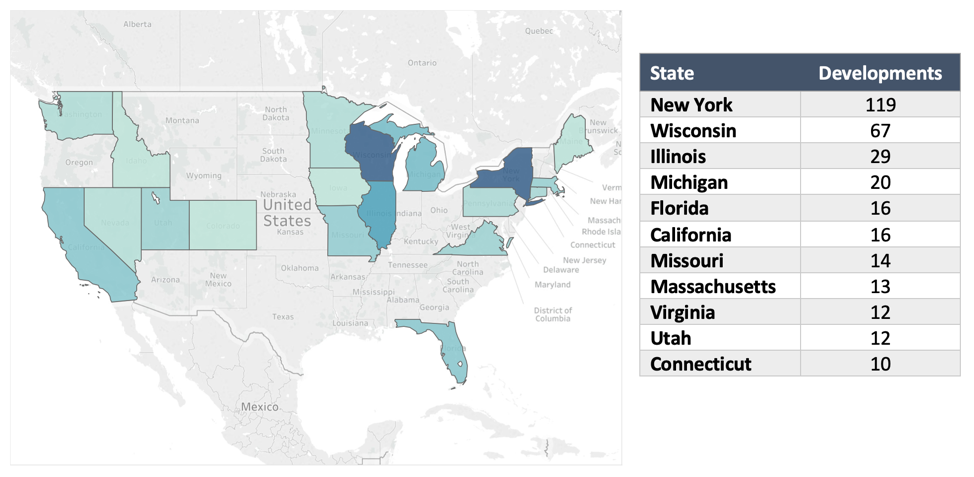

Using data available from HUD, it is possible to identify and map mixed-income LIHTC developments across the country. The map and table below show the concentration of these projects by state since 2010. Individual projects with fewer than 10 non-LIHTC units and states with fewer than 5 mixed-income developments were filtered from the analysis. States with at least 10 mixed-income developments are reported in the adjacent table.

LIHTC Projects Constructed Since 2010 with Mixed-Income Components

Overall, New York and Wisconsin significantly outperform all other states, while regional concentrations appear in the Northeast, Midwest, and West. For Wisconsin and New York, these higher concentrations are not by chance, as mixed-income developments are prioritized under each state’s Qualified Application Plan.

- Wisconsin incentivizes mixed-income developments applying for non-rural funds under the 9% credit, awarding a maximum of 12 points for such projects. This makes up 4.5% of all available points in non-rural 9% credits deals.

- Meanwhile, New York State also incentivizes mixed-income developments through their state-level low-income housing tax credit program.

Importantly, unlike some other states, the NCHFA QAP does not currently prioritize the inclusion of market rate units in LIHTC developments. Under current guidelines, developments must be entirely composed of income-restricted affordable units to maximize their award potential.

By following the examples of other states and prioritizing mixed-income within developments, North Carolina might more efficiently leverage the economic benefits associated with income diversity. While affordable housing projects like that in Durham County serve the most diverse array of incomes currently possible, changes to the QAP guidelines could elevate their potential economic impacts while encouraging income-diverse development across the state.

Matthew Hutton is a dual Master’s degree candidate in the Master of Public Administration and the Master of City & Regional Planning programs at UNC-Chapel Hill. He is also a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.