|

|

Upfront Charges for Local Government Water and Sewer CapitalBy Kara MillonziPublished November 8, 2016In the wake of a recent North Carolina Supreme Court decision invalidating certain water and sewer fees (Quality Built Homes, Inc. v. Town of Carthage), counties and municipalities across the state have been taking a closer look at their own fee schedules. (A summary of the case and its holding is here.) Through Quality Built Homes, and other relevant case law, the North Carolina courts have set out the basic outlines of the types of fees that are lawful and unlawful. Unfortunately, there is still quite a bit of grey area (or as I refer to it below, yellow light area) as to the full contours of a county’s or municipality’s authority. Each local unit must work with its attorney and, if applicable, rate-setting consultant, to determine if changes are needed to its fee schedule. The following sets out a framework to aid in that analysis. There are two primary fee statutes that authorize counties and municipalities to assess charges associated with their water and sewer systems—the general utility fee statute and the availability fee statute. This post focuses on the general utility fee statute. (Previous posts have discussed the availability fee authority for both municipalities and counties in detail. See here, here, here.) Note also that this post only looks at county and municipality authority. It does not address the fee authority of other local government entities that provide water and sewer services. General Fee Statutes As a reminder, the general utility fee statutes for both counties and municipalities provide, that the local unit “may establish and revise from time to time schedules of rents, rates, fees, charges, and penalties for the use of or the services furnished by [the local unit’s water or sewer system.]” G.S. 160A-314 (municipalities); G.S. 153A-277 (counties) (emphasis added). Many, if not most, local units’ water and sewer systems are self-supporting. Local officials rely on this fee statute to generate sufficient revenue to construct, maintain, and operate the systems (as opposed to using property tax proceeds or other general fund revenues). The authority is thus broad. In fact, setting water and sewer utility fees is a “matter for the judgment and discretion of municipal [or county] authorities, not to be invalidated by the court absent some showing of arbitrary or discriminatory action.” Town of Spring Hope v. Bissette, 53 N.C. App. 210 (1981), aff’d, 305 N.C. 248 (1982). Lawful Fees The North Carolina Supreme Court has held that the municipal general utility fee statute (G.S. 160A-314) authorized a town to assess a charge on its water and sewer customers, where the amount was calculated to cover current operating and capital costs, as well as future capital costs necessary to continue to serve the properties. See Town of Spring Hope v. Bissette, 305 N.C. 248 (1982). In Bissette, a utility customer challenged the town’s practice of periodically increasing its water and sewer rates to finance the construction, operation, and maintenance of an upgraded treatment plant. The new plant was required to maintain the town’s permit to discharge treated water. The fee at issue was assessed on all current customers of the water and sewer system. The customer refused to pay the increased amount of the fee, claiming that the town exceeded its authority in charging for “services to be furnished” as opposed to “services furnished” by the public enterprise. The Bissette court disagreed, holding instead that the fee was assessed for a service that the customer currently received. According to the court, the upgrade “was not intended to, nor did it result in, providing a new or higher level of service to the sewer system’s customers.” Id. at 251-252. When the new plant went into operation, “the customers received nothing they had not received before,” thus, the rate “did not reflect any service yet to be furnished.” Id. To the contrary, it “represented the cost of a necessary improvement to the already existing sewer system without which the Town could not continue to provide sewer service.” Id. North Carolina courts similarly have held that the general utility fee statutes authorize a local unit to charge a connection (tap) fee. A connection/tap fee typically is assessed when a property connects to the water or sewer system and is calculated to cover the direct and indirect costs of making that connection (including, but not limited to, the costs of actually installing the meter and setting up the customer account). See Atlantic Construction Co. v. City of Raleigh, 230 N.C. 365 (1949) (holding that city had authority to charge reasonable connection fees and to otherwise “fix the terms upon which the service may be rendered and its facilities used.”); Davis v. Town of Southern Pines, 1010 N.C. App. 570 (1991) (upholding town’s sewer tap fee as valid charge “for using the facilities involved.”); see also McNeil v. Harnett County, 327 N.C. 552 (1990) (noting that local government may use connection charges and monthly user fees to finance the debt associated with a capital project). Unlawful Fees A county’s or municipality’s fee authority is not unlimited, though. Focusing on the phrases “for the use of” and “the services furnished by,” the Quality Built Homes court held that the fee statutes allow a local unit “to charge for the contemporaneous use of its water and sewer services—not to collect fees for future discretionary spending.” Id. at *8. Unlike the fee statutes applicable to county water and sewer districts (and a few other local government entities that provide water and sewer services), the county and municipal fee statutes do not allow a unit to “charge for prospective services. . . .” Id. at *9. The court thus invalidated the town’s water and sewer impact fees, which were assessed on developers as a condition of receiving a development permit and were calculated to cover future maintenance and expansion costs of the water and sewer systems. Fee Framework A close review of this case law reveals that there are a two different dimensions to analyzing whether a particular water or sewer fee is assessed for “the use of” or for “services furnished by” the utility system. The first factor relates to timing. WHEN a local unit charges the fee is important. The second factor is the purpose of the fee, which generally translates into HOW the fee is calculated. Occasionally, the second factor will also involve how the fee proceeds are spent. When analyzing the potential legality of a particular water or sewer fee, it is important that a unit consider both dimensions. The following chart presents what we know for certain about a county and municipality’s water and sewer fee authority. It uses a red light (prohibited), green light (allowed) framework, and breaks down commonly charged fees according to the two different factors listed above. Note that the labels assigned to a fee are not legally significant. For example, what I label as an “impact fee” on the chart may be referred to by a local unit as a system development fee, facility fee, capital fee, etc. A county or municipality must ignore the label assigned to a fee and look at the underlying purpose and timing of the fee to determine its legality. (Click here to expand chart.) Capacity Fees What about fees that do not clearly fall in the red light or green light categories? That is where the analysis is less clear. The most common type of “yellow light” fee is a capacity fee. A capacity fee may be assessed as part of the impact fee (in other words, as a condition of development), or it may be assessed when a property actually connects to the unit’s water or sewer system. What typically makes a capacity fee different from the other fees listed on the chart, though, is how it is calculated. And, in fact, there is significant variation across local units on this factor. That variation may very well prove legally significant. Before addressing the calculation issue, a word about the timing factor. No matter how it is calculated, a local unit likely is prohibited from assessing a capacity fee before it actually has a contract with the developer or property owner either to construct/expand the necessary utility infrastructure, or to connect the property to the water or sewer system. A local unit may not impose a capacity fee, by whatever label, as a condition of plat approval, development permit issuance, or pursuant to some other regulatory requirement. The trickier issue, of course, is the legality of a capacity fee that is assessed as part of the connection/tap fee or as separate fee when the local unit enters into a contractual agreement to provide utility services to a property. Industry standards suggest three different methods for calculating capacity fees. The first method is often referred to as the “buy-in” or “reimbursement” method. The concept behind this method is that when a developer or property owner contracts to connect to the water or sewer system, he/she must pay his/her proportional share of the past investment needed to be able to serve the property. This calculation also may reflect the fact that the unit must reserve a certain amount of system capacity to serve each new customer. That capacity has an opportunity cost because it cannot be used to serve another customer. The second method is the capacity expansion method. The basis for this calculation often is the projection of capacity-expanding future capital improvements. Those projected future costs are divided by projected growth to determine a per unit amount. The third method is essentially a hybrid or combined approach. It is calculated to cover some measure of reserved capacity in the system, but it includes both past costs and potential future expansion costs. As the following chart depicts, all of the capacity fee variants fall within the yellow light area, which means we do not know for sure if this type of fee is supported by the general utility fee statutes. Based on existing precedent, there is a greater likelihood that a court would uphold some capacity fees versus others, though. For example, a capacity fee calculated according to the buy-in approach arguably is akin to the connection/tap fee that has been upheld by North Carolina courts. It reimburses the unit for actual investments needed to serve the property. On the other end of the spectrum is the capacity expansion method, that is only based on future expansion costs. This type of fee is more akin to the impact fee that was found invalid by the Quality Built Homes court. The hybrid or combined approach is harder to analyze. It may depend on whether the future costs component is based on maintenance or upgrade costs necessary to continue current service or based on expansion costs to serve new customers. (With the former more likely to be upheld than the latter.) (Click here to expand chart.) Fee Framework Webinar For more information on the Quality Built Homes case, and the current water and sewer fee framework, you may view an on-demand webinar here. (Note that the webinar was recorded on October 11, 2016.)

|

Published November 8, 2016 By Kara Millonzi

In the wake of a recent North Carolina Supreme Court decision invalidating certain water and sewer fees (Quality Built Homes, Inc. v. Town of Carthage), counties and municipalities across the state have been taking a closer look at their own fee schedules. (A summary of the case and its holding is here.) Through Quality Built Homes, and other relevant case law, the North Carolina courts have set out the basic outlines of the types of fees that are lawful and unlawful. Unfortunately, there is still quite a bit of grey area (or as I refer to it below, yellow light area) as to the full contours of a county’s or municipality’s authority. Each local unit must work with its attorney and, if applicable, rate-setting consultant, to determine if changes are needed to its fee schedule. The following sets out a framework to aid in that analysis.

There are two primary fee statutes that authorize counties and municipalities to assess charges associated with their water and sewer systems—the general utility fee statute and the availability fee statute. This post focuses on the general utility fee statute. (Previous posts have discussed the availability fee authority for both municipalities and counties in detail. See here, here, here.) Note also that this post only looks at county and municipality authority. It does not address the fee authority of other local government entities that provide water and sewer services.

General Fee Statutes

As a reminder, the general utility fee statutes for both counties and municipalities provide, that the local unit “may establish and revise from time to time schedules of rents, rates, fees, charges, and penalties for the use of or the services furnished by [the local unit’s water or sewer system.]” G.S. 160A-314 (municipalities); G.S. 153A-277 (counties) (emphasis added).

Many, if not most, local units’ water and sewer systems are self-supporting. Local officials rely on this fee statute to generate sufficient revenue to construct, maintain, and operate the systems (as opposed to using property tax proceeds or other general fund revenues). The authority is thus broad. In fact, setting water and sewer utility fees is a “matter for the judgment and discretion of municipal [or county] authorities, not to be invalidated by the court absent some showing of arbitrary or discriminatory action.” Town of Spring Hope v. Bissette, 53 N.C. App. 210 (1981), aff’d, 305 N.C. 248 (1982).

Lawful Fees

The North Carolina Supreme Court has held that the municipal general utility fee statute (G.S. 160A-314) authorized a town to assess a charge on its water and sewer customers, where the amount was calculated to cover current operating and capital costs, as well as future capital costs necessary to continue to serve the properties. See Town of Spring Hope v. Bissette, 305 N.C. 248 (1982). In Bissette, a utility customer challenged the town’s practice of periodically increasing its water and sewer rates to finance the construction, operation, and maintenance of an upgraded treatment plant. The new plant was required to maintain the town’s permit to discharge treated water. The fee at issue was assessed on all current customers of the water and sewer system. The customer refused to pay the increased amount of the fee, claiming that the town exceeded its authority in charging for “services to be furnished” as opposed to “services furnished” by the public enterprise. The Bissette court disagreed, holding instead that the fee was assessed for a service that the customer currently received. According to the court, the upgrade “was not intended to, nor did it result in, providing a new or higher level of service to the sewer system’s customers.” Id. at 251-252. When the new plant went into operation, “the customers received nothing they had not received before,” thus, the rate “did not reflect any service yet to be furnished.” Id. To the contrary, it “represented the cost of a necessary improvement to the already existing sewer system without which the Town could not continue to provide sewer service.” Id.

North Carolina courts similarly have held that the general utility fee statutes authorize a local unit to charge a connection (tap) fee. A connection/tap fee typically is assessed when a property connects to the water or sewer system and is calculated to cover the direct and indirect costs of making that connection (including, but not limited to, the costs of actually installing the meter and setting up the customer account). See Atlantic Construction Co. v. City of Raleigh, 230 N.C. 365 (1949) (holding that city had authority to charge reasonable connection fees and to otherwise “fix the terms upon which the service may be rendered and its facilities used.”); Davis v. Town of Southern Pines, 1010 N.C. App. 570 (1991) (upholding town’s sewer tap fee as valid charge “for using the facilities involved.”); see also McNeil v. Harnett County, 327 N.C. 552 (1990) (noting that local government may use connection charges and monthly user fees to finance the debt associated with a capital project).

Unlawful Fees

A county’s or municipality’s fee authority is not unlimited, though. Focusing on the phrases “for the use of” and “the services furnished by,” the Quality Built Homes court held that the fee statutes allow a local unit “to charge for the contemporaneous use of its water and sewer services—not to collect fees for future discretionary spending.” Id. at *8. Unlike the fee statutes applicable to county water and sewer districts (and a few other local government entities that provide water and sewer services), the county and municipal fee statutes do not allow a unit to “charge for prospective services. . . .” Id. at *9. The court thus invalidated the town’s water and sewer impact fees, which were assessed on developers as a condition of receiving a development permit and were calculated to cover future maintenance and expansion costs of the water and sewer systems.

Fee Framework

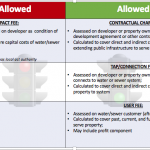

A close review of this case law reveals that there are a two different dimensions to analyzing whether a particular water or sewer fee is assessed for “the use of” or for “services furnished by” the utility system. The first factor relates to timing. WHEN a local unit charges the fee is important. The second factor is the purpose of the fee, which generally translates into HOW the fee is calculated. Occasionally, the second factor will also involve how the fee proceeds are spent. When analyzing the potential legality of a particular water or sewer fee, it is important that a unit consider both dimensions.

The following chart presents what we know for certain about a county and municipality’s water and sewer fee authority. It uses a red light (prohibited), green light (allowed) framework, and breaks down commonly charged fees according to the two different factors listed above. Note that the labels assigned to a fee are not legally significant. For example, what I label as an “impact fee” on the chart may be referred to by a local unit as a system development fee, facility fee, capital fee, etc. A county or municipality must ignore the label assigned to a fee and look at the underlying purpose and timing of the fee to determine its legality.

(Click here to expand chart.)

Capacity Fees

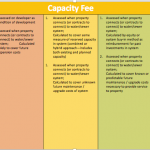

What about fees that do not clearly fall in the red light or green light categories? That is where the analysis is less clear. The most common type of “yellow light” fee is a capacity fee. A capacity fee may be assessed as part of the impact fee (in other words, as a condition of development), or it may be assessed when a property actually connects to the unit’s water or sewer system. What typically makes a capacity fee different from the other fees listed on the chart, though, is how it is calculated. And, in fact, there is significant variation across local units on this factor. That variation may very well prove legally significant.

Before addressing the calculation issue, a word about the timing factor. No matter how it is calculated, a local unit likely is prohibited from assessing a capacity fee before it actually has a contract with the developer or property owner either to construct/expand the necessary utility infrastructure, or to connect the property to the water or sewer system. A local unit may not impose a capacity fee, by whatever label, as a condition of plat approval, development permit issuance, or pursuant to some other regulatory requirement.

The trickier issue, of course, is the legality of a capacity fee that is assessed as part of the connection/tap fee or as separate fee when the local unit enters into a contractual agreement to provide utility services to a property. Industry standards suggest three different methods for calculating capacity fees. The first method is often referred to as the “buy-in” or “reimbursement” method. The concept behind this method is that when a developer or property owner contracts to connect to the water or sewer system, he/she must pay his/her proportional share of the past investment needed to be able to serve the property. This calculation also may reflect the fact that the unit must reserve a certain amount of system capacity to serve each new customer. That capacity has an opportunity cost because it cannot be used to serve another customer.

The second method is the capacity expansion method. The basis for this calculation often is the projection of capacity-expanding future capital improvements. Those projected future costs are divided by projected growth to determine a per unit amount.

The third method is essentially a hybrid or combined approach. It is calculated to cover some measure of reserved capacity in the system, but it includes both past costs and potential future expansion costs.

As the following chart depicts, all of the capacity fee variants fall within the yellow light area, which means we do not know for sure if this type of fee is supported by the general utility fee statutes. Based on existing precedent, there is a greater likelihood that a court would uphold some capacity fees versus others, though. For example, a capacity fee calculated according to the buy-in approach arguably is akin to the connection/tap fee that has been upheld by North Carolina courts. It reimburses the unit for actual investments needed to serve the property. On the other end of the spectrum is the capacity expansion method, that is only based on future expansion costs. This type of fee is more akin to the impact fee that was found invalid by the Quality Built Homes court. The hybrid or combined approach is harder to analyze. It may depend on whether the future costs component is based on maintenance or upgrade costs necessary to continue current service or based on expansion costs to serve new customers. (With the former more likely to be upheld than the latter.)

(Click here to expand chart.)

Fee Framework Webinar

For more information on the Quality Built Homes case, and the current water and sewer fee framework, you may view an on-demand webinar here. (Note that the webinar was recorded on October 11, 2016.)

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.