|

|

American Rescue Plan: Local Government Funding for Affordable Housing DevelopmentBy Tyler MulliganPublished June 1, 2021UPDATE: In July 2022, U.S. Treasury and HUD jointly released an “Affordable Housing How-To Guide” here: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Affordable-Housing-How-To-Guide.pdf. Please consult that document in conjunction with the state law information provided below and in charts here and here. The federal American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP) established Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“FRF”), which will be distributed to state and local governments for the purpose of responding “to the public health emergency with respect to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID–19) or its negative economic impacts, including assistance to households, small businesses, and nonprofits, or aid to impacted industries such as tourism, travel, and hospitality” (Part 8, Subtitle M of ARP). The amounts to be distributed are substantial. The U.S. Department of Treasury (“Treasury”) lists the county-by-county distributions here and the allocations for “entitlement” cities here. The Interim Final Rule, promulgated by Treasury and codified at Part 35 of Subtitle A of Title 31 of the Code of Federal Regulations, recognizes “a broad range of eligible uses” for FRF, and offers local governments “flexibility to determine how best to use payments.” Although the rule is still “interim” and therefore leaves some details to be finalized, public officials are beginning to plan how they will utilize the infusion of funding. This post is designed to inform those initial planning discussions at the local level, and it will be updated when/if the “interim final rule” is revised. UPDATE: In an “explainer” on the Interim Final Rule, Treasury confirmed that “Funds used in a manner consistent with the Interim Final Rule while the Interim Final Rule is effective will not be subject to recoupment.” There are many possible uses of FRF, ranging from premium pay for essential workers, to water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure. One particular category of potential FRF-eligible activities has generated a good deal of interest and questions from public officials: 31 C.F.R. 35.6(b)(12)(ii)(B) authorizes FRF to be used for “[d]evelopment of affordable housing to increase supply of affordable and high-quality living units.” The federal definition of “affordable” housing is that a household spends no more than 30% of gross income on housing costs, which for renters includes utilities, and for owners includes mortgage, utilities, HOA dues, property taxes, and insurance. The mere fact that the federal government approves a particular use of FRF does not mean a North Carolina local government possesses legal authority to engage in that activity. As my colleague Kara Millonzi explains in an earlier post, all local government activities must also comply with state law requirements. This post first reviews the extent to which Treasury guidelines allow FRF to be used for affordable housing development, and then it explains how North Carolina law applies. The federal rules: affordable housing development as an eligible use of FRFWhat is the general test for eligible uses of FRF? In general, for a program, service, or other assistance to be eligible for FRF, it must “respond to the public health emergency or its negative economic impacts.” 31 CFR 35.6(b). The Treasury guidance offers a two prong test to determine whether this threshold is met:

What sort of affordable housing activities can be supported with FRF?

Who must benefit?

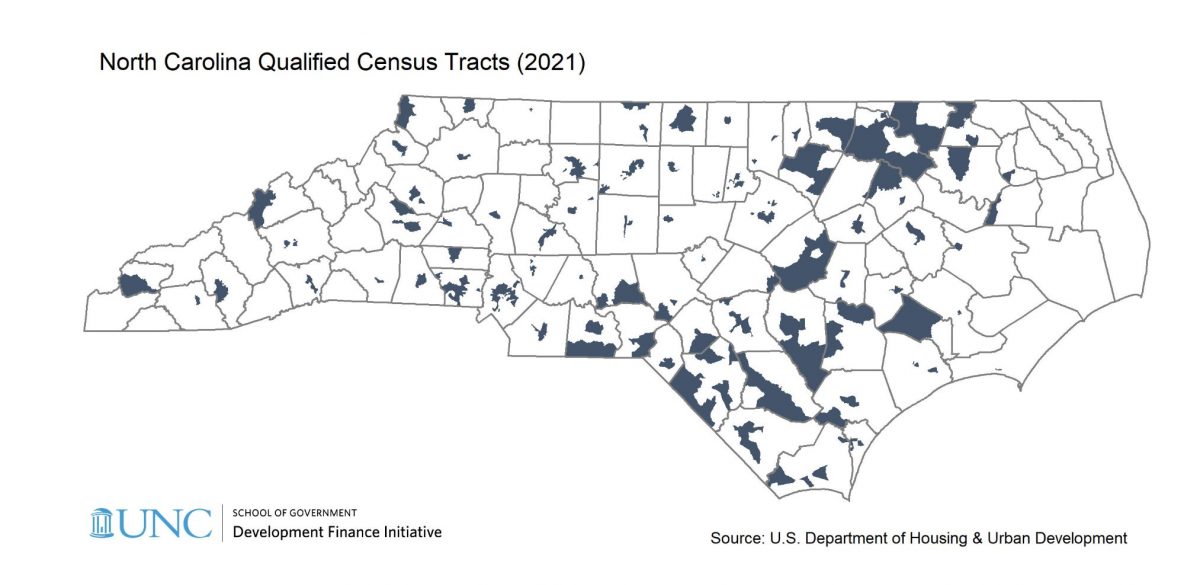

What are QCTs? QCTs are census tracts designated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as meeting certain distress indicators. An interactive map of QCTs can be found on the HUD website here. North Carolina QCTs are shown in the map below. What key findings and determinations should local governments make to support use of FRF for development of affordable housing?

State law: How North Carolina local governments may employ FRF for affordable housing developmentWhile it is true that Treasury guidance grants “broad latitude” to local governments and “flexibility to determine how best to use payments,” this does not mean that local governments are free to employ FRF in any manner authorized by the federal government. All local government activities must also comply with state law requirements. When federal and state laws conflict with each other, local governments are required to follow the most restrictive rule. The remainder of this post explains how North Carolina local governments can engage in FRF-eligible affordable housing repair, renovation, or development in compliance with constitutional requirements and state statutes. Complying with the North Carolina ConstitutionArticle 1, Section 32 of the North Carolina Constitution prohibits governments from making gifts to private persons or entities “but in consideration of [in exchange for] public services” (see Frayda Bluestein’s blog post discussing this provision). In other words, a local government must receive valuable public service in return for any cash it pays to someone. Further, the state constitution permits local governments to expend funds “for public purposes only.” Every expenditure must therefore serve a constitutional public purpose, and the North Carolina Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter of what does or does not serve a public purpose. If an expenditure serves a public purpose, then it satisfies the constitution’s gift clause as well. In the context of FRF, direct aid to the poor, disaster aid, and provision of affordable housing all serve a permissible public purpose. Each is described in turn. Aid to “the poor” (or low-income households) The North Carolina Constitution declares that it is “one of the first duties of a civilized and a Christian state” to aid “the poor, the unfortunate, and the orphan.” In other words, it is always constitutionally permissible to provide direct aid to individuals in need, whether during an emergency or not. For example, the North Carolina Supreme Court has authorized loans for education for those “of slender means,” State Education Assistance Authority v. Bank of Statesville, 276 N.C. 576 (1970); and loans for veterans to purchase homes, Hinton v. Lacy, 193 N.C. 496 (1927). This principle, that aid to the poor (or low income) is permissible, holds true regardless of whether there is an immediate emergency. FRF activities that benefit low-income persons would therefore be consistent with the state constitution. Disaster aid “properly tailored to address the immediate emergency” In the context of disaster aid, the North Carolina Attorney General, in a formal opinion authored in 1999, examined whether the state constitution allowed the General Assembly to provide disaster aid to individuals (including higher income individuals and businesses who suffered substantial damage) and opined that it was permissible. The Attorney General noted the state constitution’s language regarding the state’s “first duty” to aid the “poor” and the “unfortunate,” and concluded that aid to individuals in need can serve a public purpose under the North Carolina Constitution, provided the program is properly tailored to address the immediate emergency. The example provided in the opinion said that aid should be limited to those persons who “suffered substantial damage as a consequence of the disaster” and “who have not otherwise been fully compensated for that damage.” The Attorney General opinion seems to align with FRF eligibility, which requires a local government to determine that an economic harm exists and “was made worse by COVID-19,” and which requires any response to be “related and reasonably proportional to the extent and type of harm experienced.” In the context of a worldwide pandemic, FRF is designed to address the “substantial damage” (using the Attorney General’s words) that was experienced in the form of unemployment and food and housing insecurity. Treasury guidance assumes that substantial (uncompensated) damage occurred to low-income persons and those living in QCTs, and it provides citations to research in support of its assumption. Affordable housing when “private enterprise is unable to meet the need” With respect to affordable housing, the North Carolina Supreme Court long ago determined that providing affordable housing to persons of low income serves a constitutional public purpose. Wells v. Hous. Auth. of City of Wilmington, 213 N.C. 744, 197 S.E. 693, 696 (1938). Housing financing (loans) for persons of “moderate incomes” also serves a public purpose when the legislature is “acting with the same public purpose in mind” as when assisting persons of low income; In re Denial of Approval to Issue $30,000,000.00 of Single Family Hous. Bonds & $30,000,000.00 of Multi-Family Hous. Bonds for Persons of Moderate Income, 307 N.C. 52, 60-61, 296 S.E.2d 281, 286 (1982). Note, however, the constitutionality of affordable housing activities is conditioned on the necessity of the activities—that is, the activities serve a public purpose “only when the planning, construction, and financing of decent residential housing is not otherwise available” because “private enterprise is unable to meet the need.” Id at 59-61; Martin v. North Carolina Housing Corp., 277 N.C. 29, 50, 175 S.E.2d 665, 677 (1970). For a high level assessment of whether private enterprise is meeting the housing needs of low income persons in a particular community, see the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency’s “housing snapshot.” Complying with North Carolina statutory authorityAs a general rule, the state constitution provides that a local government must be granted statutory authority to engage in any activity. In addition, where an authorizing statute exists, it must be applied by a local government in a constitutional manner. For example, even if the General Assembly were to enact an overly broad statute that purports to go beyond the limits of the state constitution, local governments should apply the statute in a way that remains within the bounds of the constitution. “We have repeatedly held that as between two possible interpretations of a statute, by one of which it would be unconstitutional and by the other valid, our plain duty is to adopt that which will save the act. Even to avoid a serious doubt the rule is the same.” In re Dairy Farms, 289 N.C. 456, 465, 223 S.E.2d 323, 328-29 (1976) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted). Specific North Carolina statutes related to FRF-eligible housing activities are described below. Emergency assistance for home repairs or weatherization Emergency home repair and weatherization programs for low income persons are not a new concept. Federal funding, such as Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), has been used for that purpose for decades. G.S. 160D-1311(a) authorizes local governments to establish “community development programs,” including “rehabilitation of private buildings principally for the benefit of low- and moderate-income persons” and providing for the “welfare needs of persons of low and moderate income.” There are two important points to note: (1) recipients of this aid must meet an income test, and (2) the reference to “community development programs” refers to federal programs, such as CDBG, which provide funding for activities that benefit low-income and moderate-income persons. FRF is not, as a technical matter, a community development program, but it operates similarly when used for the benefit of low income persons. G.S. 160D-1311 therefore provides ample authority to use FRF for emergency home repair or weatherization for persons of low and moderate income. G.S. 157-3 defines persons of low income as those earning 60% of area median income (AMI) or below. Moderate income has a more flexible definition in state law, but is generally understood to mean 60%-80% AMI because households up to 80% AMI are the focus of other federal programs (such as CDBG). Note that the state definition of low income (60% AMI or below) is different from the federal definition of low income (80% AMI or below). Local government authority to develop or rehabilitate affordable housing There are several statutory regimes which authorize local governments to engage in development of affordable housing. Housing authority powers G.S. 160D-1311(b) authorizes a municipal or county governing board to exercise directly those powers granted to housing authorities in G.S. Chapter 157. A housing authority possesses broad powers to develop and rehabilitate affordable housing for persons of low and moderate income (as defined under state law). To summarize:

Development of affordable housing without relying on housing authority powers G.S. 160D-1316 empowers local governments to construct affordable housing, acquire property for development of housing, and convey that property for later development and use as affordable housing, under essentially the same parameters as a housing authority. However, unlike the housing authority powers, this statute does not authorize a local government to operate housing, nor to subsidize a private developer or operator of affordable housing. To engage in those activities, a local government would need to rely on housing authority powers as described above. Lease of land for development of affordable housing G.S. 160A-278 authorizes a local government to lease land to any firm for the construction of affordable housing for persons of low and moderate income. Such land obviously returns to public ownership at the conclusion of the lease. Conveyance of property to a nonprofit for development of affordable housing G.S. 160A-279 authorizes a local government to convey property by private sale to a nonprofit of its choice. Whenever a local government is authorized to appropriate funds to a not-for-profit entity carrying out a public purpose, the local government is also permitted to convey property “by private sale” to that entity “in lieu of or in addition to the appropriation of funds.” As noted earlier, private sale means that the local government may choose its buyer rather than undergoing a competitive bidding process. The local government must attach “covenants or conditions” to the conveyance to ensure that (1) the property will be “put to a public use by the recipient entity” and (2) that the property reverts back to government ownership when no longer so used, as explained in Frayda Bluestein’s blog post here. Low and moderate income homeownership Support for homeownership opportunities for low and moderate income persons is a separate category. Down payment assistance and direct sale to low income persons with subsidized sale prices is permitted when exercising housing authority powers (G.S. Chapter 157 pursuant to G.S. 160D-1311). Moderate income persons (typically 60-80% AMI) may also be aided with low interest loans when the local government is “acting with the same public purpose in mind” as with low income persons. In re Denial of Approval to Issue $30,000,000.00 of Single Family Hous. Bonds & $30,000,000.00 of Multi-Family Hous. Bonds for Persons of Moderate Income, 307 N.C. 52 (1982). There is separate authority in G.S. 160D-1316(4) for conveying residential property directly to persons of low and moderate income (as defined by state law) using private sale procedures. Need help? Assistance with strategic planning and affordable housing activitiesAs North Carolina public officials know well from their experience with federal disaster recovery funding, the sudden infusion of federal dollars from a program like FRF can strain the capacity of local government elected officials and staff. Trying to plan and implement new activities using unprecedented levels of federal funding is no easy task. Perhaps in anticipation of this concern, Treasury explicitly authorizes FRF to be used “to improve efficacy of programs addressing negative economic impacts [of COVID-19], including through use of data analysis, targeted consumer outreach, improvements to data or technology infrastructure, and impact evaluations.” Interim Final Rule, p. 30. See also 31 C.F.R. 35.6(b)(10) (listing as an eligible use “Administrative costs associated with … services responding to the COVID-19 public health emergency or its negative economic impacts….”). It is hoped that this “efficacy” funding will provide local governments with the resources they need to engage in strategic planning (with partners such as the Center for Public Leadership and Governance at the School of Government). With respect to affordable housing development, it is advisable for local governments to collect and analyze housing data in order to inform local decision-making. A good start involves evaluating community housing needs, analyzing housing infrastructure, and anticipating future housing supply based on an understanding of the private market’s capacity to produce housing. It also requires communicating with public and private stakeholders, identifying suitable development sites, conducting market analysis, and creating housing development programs that are financially feasible and grounded in market realities. Given the uniqueness of this moment, most local governments probably don’t possess the staff capacity and skillsets to conduct the necessary analysis and implement the selected strategies for such a large amount of funding. Consider enlisting the help of regional councils of government (COGs), which have experience with managing federal grants, and seek assistance from public-minded development experts such as the Development Finance Initiative (DFI) at the School of Government. Armed with housing data and market analysis, an understanding of the community’s needs, and feasible development plans grounded in market realities, local government leaders will be prepared to employ FRF to maximum effect. |

Published June 1, 2021 By Tyler Mulligan

UPDATE: In July 2022, U.S. Treasury and HUD jointly released an “Affordable Housing How-To Guide” here: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/Affordable-Housing-How-To-Guide.pdf. Please consult that document in conjunction with the state law information provided below and in charts here and here.

The federal American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP) established Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (“FRF”), which will be distributed to state and local governments for the purpose of responding “to the public health emergency with respect to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID–19) or its negative economic impacts, including assistance to households, small businesses, and nonprofits, or aid to impacted industries such as tourism, travel, and hospitality” (Part 8, Subtitle M of ARP). The amounts to be distributed are substantial. The U.S. Department of Treasury (“Treasury”) lists the county-by-county distributions here and the allocations for “entitlement” cities here.

The Interim Final Rule, promulgated by Treasury and codified at Part 35 of Subtitle A of Title 31 of the Code of Federal Regulations, recognizes “a broad range of eligible uses” for FRF, and offers local governments “flexibility to determine how best to use payments.” Although the rule is still “interim” and therefore leaves some details to be finalized, public officials are beginning to plan how they will utilize the infusion of funding. This post is designed to inform those initial planning discussions at the local level, and it will be updated when/if the “interim final rule” is revised.

UPDATE: In an “explainer” on the Interim Final Rule, Treasury confirmed that “Funds used in a manner consistent with the Interim Final Rule while the Interim Final Rule is effective will not be subject to recoupment.”

There are many possible uses of FRF, ranging from premium pay for essential workers, to water, sewer, and broadband infrastructure. One particular category of potential FRF-eligible activities has generated a good deal of interest and questions from public officials: 31 C.F.R. 35.6(b)(12)(ii)(B) authorizes FRF to be used for “[d]evelopment of affordable housing to increase supply of affordable and high-quality living units.” The federal definition of “affordable” housing is that a household spends no more than 30% of gross income on housing costs, which for renters includes utilities, and for owners includes mortgage, utilities, HOA dues, property taxes, and insurance.

The mere fact that the federal government approves a particular use of FRF does not mean a North Carolina local government possesses legal authority to engage in that activity. As my colleague Kara Millonzi explains in an earlier post, all local government activities must also comply with state law requirements. This post first reviews the extent to which Treasury guidelines allow FRF to be used for affordable housing development, and then it explains how North Carolina law applies.

The federal rules: affordable housing development as an eligible use of FRF

What is the general test for eligible uses of FRF? In general, for a program, service, or other assistance to be eligible for FRF, it must “respond to the public health emergency or its negative economic impacts.” 31 CFR 35.6(b). The Treasury guidance offers a two prong test to determine whether this threshold is met:

- In responding to negative economic impacts, a local government “should first consider whether an economic harm exists and whether this harm was caused or made worse by the COVID-19 public health emergency.” Interim Final Rule, p. 27. The Treasury guidance is replete with citations to studies indicating that low-income households and households facing housing insecurity (among other conditions) were harmed by the pandemic to a greater degree than other populations. Interim Final Rule, p. 22, 25, 26. Accordingly, programs that benefit low-income households meet this prong of the eligibility test.

- “Responses must be related and reasonably proportional to the extent and type of harm experienced; uses that bear no relation or are grossly disproportionate to the type or extent of harm experienced would not be eligible uses.” Interim Final Rule, p. 28. Within those constraints, local governments are granted “broad latitude” to determine “whether and how” to use FRF. Id. As already mentioned, development of affordable housing for low income persons is specifically listed as a reasonable response.

What sort of affordable housing activities can be supported with FRF?

- Increasing supply of affordable and high-quality units. Among the “non-exclusive list” of eligible uses of FRF are programs that address “housing insecurity, lack of affordable housing, or homelessness,” including but not limited to “[d]evelopment of affordable housing to increase the supply of affordable and high-quality living units.” 31 CFR 35.6(b)(12)(ii). Thus, new development of high-quality affordable housing is clearly an eligible use of FRF. It logically follows that redevelopment or renovation of housing is also an eligible use of FRF when it increases the supply of affordable and high-quality units.

- Emergency home repairs for eligible households. The guidance specifically authorizes “emergency assistance to households” for “home repairs, weatherization, or other needs,” regardless of housing quality, so long as the assistance benefits qualifying households. Interim Final Rule, p. 29, 31 CFR 35.6(b)(8). This means that low quality housing can be repaired using FRF so long as it benefits low-income households who require the “emergency assistance.” Such “emergency assistance” for necessary repairs is an activity separate and apart from “development” of high-quality affordable housing.

- What isn’t covered? It remains unclear whether FRF can be used for development or non-emergency renovation that produces low-quality housing (such as poorly constructed or inefficient housing). Treasury guidance contains no definition of “high-quality living units.” It bears repeating that Treasury guidance grants “broad latitude” to local governments in designing FRF programs and services. When a local government isn’t sure whether its activity is explicitly approved in the guidance (for example, it isn’t sure that the housing will be “high-quality,” or the housing will not be permanently “affordable”), it should prepare a special justification for engaging in the activity.

Who must benefit?

- Automatic geographic eligibility for affordable housing (31 CFR 35.6(b)(12)) for any of the following:

- The affordable housing is located in a qualified census tract (QCT), which is a distressed census tract designated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). QCTs are further described below.

- The affordable housing is provided to households and populations who live in a QCT.

- Automatic household eligibility for assistance to households in the form of “home repairs, weatherization, or other needs” (Interim Final Rule, p. 29; 31 CFR 35.6(b)(8)) for any of the following:

- The assistance is provided to households that experienced unemployment during the public health emergency.

- The assistance is provided to households that experienced increased food or housing insecurity during the public health emergency.

- The assistance is provided to households that are low- or moderate-income.

- Locally Determined Eligibility (Interim Final Rule, p. 20): Locally-defined populations or geographic areas may be served so long as local officials can “support their determination that the pandemic resulted in disproportionate public health or economic outcomes” for the “specific populations, households, or geographic areas to be served.”

- UPDATE v1: The first version of the FRF Compliance and Reporting Guide (Version 1.1, June 24, 2021) advises on page 17 that local governments may assume the following are “targeted towards economically disadvantaged communities”:

- A program or service for which the eligibility criteria are such that the primary intended beneficiaries earn less than 60 percent of the median income for the relevant jurisdiction (e.g., State, county, metropolitan area, or other jurisdiction); or

- A program or service for which the eligibility criteria are such that over 25 percent of intended beneficiaries are below the federal poverty line.

- UPDATE v2: The second version of FRF Compliance and Reporting Guide (Version 2.1, November 5, 2021) removes the language from v1 described above and states instead that recipients are encouraged to direct funds toward disproportionately impacted communities and that requirements for reporting will be “released after the issuance of the Fiscal Recovery Fund Final Rule.”

- UPDATE v1: The first version of the FRF Compliance and Reporting Guide (Version 1.1, June 24, 2021) advises on page 17 that local governments may assume the following are “targeted towards economically disadvantaged communities”:

What are QCTs? QCTs are census tracts designated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as meeting certain distress indicators. An interactive map of QCTs can be found on the HUD website here. North Carolina QCTs are shown in the map below.

What key findings and determinations should local governments make to support use of FRF for development of affordable housing?

- Whether an economic harm exists and whether it was made worse by COVID-19. Make findings regarding one of the following:

- Automatic geographic eligibility,

- Automatic household eligibility, OR

- Locally determined eligibility (must provide additional support for rationale)

- How the FRF expenditure for development of housing is related and reasonably proportional to the extent and type of harm experienced. Include findings regarding one of the following:

- Describe activity already approved in FRF guidance:

- emergency home repairs and weatherization for eligible households

- development of affordable housing to increase the supply of affordable and high-quality living units

- OR describe activity not listed in Treasury guidance and provide the required additional justification. For example, additional justification would be required to use FRF for non-emergency repair or renovation that does not “increase the supply” of both “affordable and high-quality living units” (because the resulting housing is not affordable and/or not high quality).

- Describe activity already approved in FRF guidance:

State law: How North Carolina local governments may employ FRF for affordable housing development

While it is true that Treasury guidance grants “broad latitude” to local governments and “flexibility to determine how best to use payments,” this does not mean that local governments are free to employ FRF in any manner authorized by the federal government. All local government activities must also comply with state law requirements. When federal and state laws conflict with each other, local governments are required to follow the most restrictive rule. The remainder of this post explains how North Carolina local governments can engage in FRF-eligible affordable housing repair, renovation, or development in compliance with constitutional requirements and state statutes.

Complying with the North Carolina Constitution

Article 1, Section 32 of the North Carolina Constitution prohibits governments from making gifts to private persons or entities “but in consideration of [in exchange for] public services” (see Frayda Bluestein’s blog post discussing this provision). In other words, a local government must receive valuable public service in return for any cash it pays to someone. Further, the state constitution permits local governments to expend funds “for public purposes only.” Every expenditure must therefore serve a constitutional public purpose, and the North Carolina Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter of what does or does not serve a public purpose. If an expenditure serves a public purpose, then it satisfies the constitution’s gift clause as well.

In the context of FRF, direct aid to the poor, disaster aid, and provision of affordable housing all serve a permissible public purpose. Each is described in turn.

Aid to “the poor” (or low-income households)

The North Carolina Constitution declares that it is “one of the first duties of a civilized and a Christian state” to aid “the poor, the unfortunate, and the orphan.” In other words, it is always constitutionally permissible to provide direct aid to individuals in need, whether during an emergency or not. For example, the North Carolina Supreme Court has authorized loans for education for those “of slender means,” State Education Assistance Authority v. Bank of Statesville, 276 N.C. 576 (1970); and loans for veterans to purchase homes, Hinton v. Lacy, 193 N.C. 496 (1927). This principle, that aid to the poor (or low income) is permissible, holds true regardless of whether there is an immediate emergency. FRF activities that benefit low-income persons would therefore be consistent with the state constitution.

Disaster aid “properly tailored to address the immediate emergency”

In the context of disaster aid, the North Carolina Attorney General, in a formal opinion authored in 1999, examined whether the state constitution allowed the General Assembly to provide disaster aid to individuals (including higher income individuals and businesses who suffered substantial damage) and opined that it was permissible. The Attorney General noted the state constitution’s language regarding the state’s “first duty” to aid the “poor” and the “unfortunate,” and concluded that aid to individuals in need can serve a public purpose under the North Carolina Constitution, provided the program is properly tailored to address the immediate emergency. The example provided in the opinion said that aid should be limited to those persons who “suffered substantial damage as a consequence of the disaster” and “who have not otherwise been fully compensated for that damage.”

The Attorney General opinion seems to align with FRF eligibility, which requires a local government to determine that an economic harm exists and “was made worse by COVID-19,” and which requires any response to be “related and reasonably proportional to the extent and type of harm experienced.” In the context of a worldwide pandemic, FRF is designed to address the “substantial damage” (using the Attorney General’s words) that was experienced in the form of unemployment and food and housing insecurity. Treasury guidance assumes that substantial (uncompensated) damage occurred to low-income persons and those living in QCTs, and it provides citations to research in support of its assumption.

Affordable housing when “private enterprise is unable to meet the need”

With respect to affordable housing, the North Carolina Supreme Court long ago determined that providing affordable housing to persons of low income serves a constitutional public purpose. Wells v. Hous. Auth. of City of Wilmington, 213 N.C. 744, 197 S.E. 693, 696 (1938). Housing financing (loans) for persons of “moderate incomes” also serves a public purpose when the legislature is “acting with the same public purpose in mind” as when assisting persons of low income; In re Denial of Approval to Issue $30,000,000.00 of Single Family Hous. Bonds & $30,000,000.00 of Multi-Family Hous. Bonds for Persons of Moderate Income, 307 N.C. 52, 60-61, 296 S.E.2d 281, 286 (1982). Note, however, the constitutionality of affordable housing activities is conditioned on the necessity of the activities—that is, the activities serve a public purpose “only when the planning, construction, and financing of decent residential housing is not otherwise available” because “private enterprise is unable to meet the need.” Id at 59-61; Martin v. North Carolina Housing Corp., 277 N.C. 29, 50, 175 S.E.2d 665, 677 (1970). For a high level assessment of whether private enterprise is meeting the housing needs of low income persons in a particular community, see the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency’s “housing snapshot.”

Complying with North Carolina statutory authority

As a general rule, the state constitution provides that a local government must be granted statutory authority to engage in any activity. In addition, where an authorizing statute exists, it must be applied by a local government in a constitutional manner. For example, even if the General Assembly were to enact an overly broad statute that purports to go beyond the limits of the state constitution, local governments should apply the statute in a way that remains within the bounds of the constitution. “We have repeatedly held that as between two possible interpretations of a statute, by one of which it would be unconstitutional and by the other valid, our plain duty is to adopt that which will save the act. Even to avoid a serious doubt the rule is the same.” In re Dairy Farms, 289 N.C. 456, 465, 223 S.E.2d 323, 328-29 (1976) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted).

Specific North Carolina statutes related to FRF-eligible housing activities are described below.

Emergency assistance for home repairs or weatherization

Emergency home repair and weatherization programs for low income persons are not a new concept. Federal funding, such as Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), has been used for that purpose for decades. G.S. 160D-1311(a) authorizes local governments to establish “community development programs,” including “rehabilitation of private buildings principally for the benefit of low- and moderate-income persons” and providing for the “welfare needs of persons of low and moderate income.” There are two important points to note: (1) recipients of this aid must meet an income test, and (2) the reference to “community development programs” refers to federal programs, such as CDBG, which provide funding for activities that benefit low-income and moderate-income persons. FRF is not, as a technical matter, a community development program, but it operates similarly when used for the benefit of low income persons.

G.S. 160D-1311 therefore provides ample authority to use FRF for emergency home repair or weatherization for persons of low and moderate income. G.S. 157-3 defines persons of low income as those earning 60% of area median income (AMI) or below. Moderate income has a more flexible definition in state law, but is generally understood to mean 60%-80% AMI because households up to 80% AMI are the focus of other federal programs (such as CDBG). Note that the state definition of low income (60% AMI or below) is different from the federal definition of low income (80% AMI or below).

Local government authority to develop or rehabilitate affordable housing

There are several statutory regimes which authorize local governments to engage in development of affordable housing.

Housing authority powers

G.S. 160D-1311(b) authorizes a municipal or county governing board to exercise directly those powers granted to housing authorities in G.S. Chapter 157. A housing authority possesses broad powers to develop and rehabilitate affordable housing for persons of low and moderate income (as defined under state law). To summarize:

-

-

- Support publicly owned affordable housing. Housing authority powers enable local governments and housing authorities to construct, own, and operate housing for low income persons. Housing projects must have rents set “at the lowest possible rates consistent with … providing decent, safe, and sanitary dwelling accommodations” and the housing project cannot be constructed or operated to “provide revenues for other activities.” G.S. 157-29.

- Support for privately owned affordable housing. Direct financial support to a private housing project is authorized, subject to constraints. For any “multi-family rental housing project” receiving support, at least 20% of the units must be restricted for the “exclusive use” of low income persons (60% AMI or below). In addition, the restrictions must be in place for “at least fifteen years.” G.S. 157-3, 157-9.4. Accountability is required to ensure all subsidy amounts are traceable to direct financial benefit for low income residents, not private owners, in order to satisfy constitutional prohibitions against making gifts to private entities and to meet statutory requirements that ensure public subsidy does not “provide revenues for other activities.” Thus, any financial support provided to a housing project should not exceed the total rent reduction or down payment assistance provided to low income residents over the life of the project.

- Conveyance of property to private providers of affordable housing. The requirements for conveyance of property to private providers of affordable housing are outlined in a blog post on the topic here. Some principles to keep in mind:

- Private sale authorized. Local governments typically must convey property through a competitive bidding process to ensure open and transparent opportunity for buyers. However, in order to ensure property is used for affordable housing for low income persons, a local government may forgo the competitive process and opt for private sale instead. G.S. 157-9. Private sale enables the government to choose a buyer who promises to use the property for affordable housing, and the government may subject the property to covenants or deed restrictions to secure the promise.

- Sale price in a private sale. The sale price set by a properly conducted bid process is deemed to be fair market value by the courts—even when that price is very low. When property is sold by private sale, however, there is no bidding process upon which to rely, so the fair market value should be determined by an appraisal in order to comply with constitutional provisions prohibiting making gifts of public property. See also G.S. 160D-1312(4). Placing mandatory affordability restrictions on property will undoubtedly reduce its fair market value because the property cannot earn as much income as other similar properties. A reduction in appraised value (and sale price) attributable to reduced income potential is not a subsidy to the buyer; rather, the appraiser simply “prices in” the affordability restrictions and determines an adjusted fair value for the property. For an example of an application of this principle in the tax appraisal context (which is similar to but not the same as a professional market appraisal), see my colleague Chris McLaughlin’s blog post on the effect of the income approach on appraisal of affordable housing.

- Subsidy or discount on sale price. As just explained, local governments must receive fair market value when selling property. Local governments are not permitted to make donations of property, even to charitable entities (see my colleague Frayda Bluestein’s blog post on this topic here). As noted already, however, it is constitutionally permissible for local governments to provide welfare to low income persons as a “first duty” to aid the “poor.” If a subsidy is provided to an intermediary organization (e.g., through a discount on the sale price), that subsidy should be traceable to direct financial benefit received by low income residents. A discount on price below the appraised value, for example, should not exceed the direct subsidy provided to low income residents over the life of the project.

-

Development of affordable housing without relying on housing authority powers

G.S. 160D-1316 empowers local governments to construct affordable housing, acquire property for development of housing, and convey that property for later development and use as affordable housing, under essentially the same parameters as a housing authority. However, unlike the housing authority powers, this statute does not authorize a local government to operate housing, nor to subsidize a private developer or operator of affordable housing. To engage in those activities, a local government would need to rely on housing authority powers as described above.

Lease of land for development of affordable housing

G.S. 160A-278 authorizes a local government to lease land to any firm for the construction of affordable housing for persons of low and moderate income. Such land obviously returns to public ownership at the conclusion of the lease.

Conveyance of property to a nonprofit for development of affordable housing

G.S. 160A-279 authorizes a local government to convey property by private sale to a nonprofit of its choice. Whenever a local government is authorized to appropriate funds to a not-for-profit entity carrying out a public purpose, the local government is also permitted to convey property “by private sale” to that entity “in lieu of or in addition to the appropriation of funds.” As noted earlier, private sale means that the local government may choose its buyer rather than undergoing a competitive bidding process. The local government must attach “covenants or conditions” to the conveyance to ensure that (1) the property will be “put to a public use by the recipient entity” and (2) that the property reverts back to government ownership when no longer so used, as explained in Frayda Bluestein’s blog post here.

Low and moderate income homeownership

Support for homeownership opportunities for low and moderate income persons is a separate category. Down payment assistance and direct sale to low income persons with subsidized sale prices is permitted when exercising housing authority powers (G.S. Chapter 157 pursuant to G.S. 160D-1311). Moderate income persons (typically 60-80% AMI) may also be aided with low interest loans when the local government is “acting with the same public purpose in mind” as with low income persons. In re Denial of Approval to Issue $30,000,000.00 of Single Family Hous. Bonds & $30,000,000.00 of Multi-Family Hous. Bonds for Persons of Moderate Income, 307 N.C. 52 (1982).

There is separate authority in G.S. 160D-1316(4) for conveying residential property directly to persons of low and moderate income (as defined by state law) using private sale procedures.

Need help? Assistance with strategic planning and affordable housing activities

As North Carolina public officials know well from their experience with federal disaster recovery funding, the sudden infusion of federal dollars from a program like FRF can strain the capacity of local government elected officials and staff. Trying to plan and implement new activities using unprecedented levels of federal funding is no easy task. Perhaps in anticipation of this concern, Treasury explicitly authorizes FRF to be used “to improve efficacy of programs addressing negative economic impacts [of COVID-19], including through use of data analysis, targeted consumer outreach, improvements to data or technology infrastructure, and impact evaluations.” Interim Final Rule, p. 30. See also 31 C.F.R. 35.6(b)(10) (listing as an eligible use “Administrative costs associated with … services responding to the COVID-19 public health emergency or its negative economic impacts….”).

It is hoped that this “efficacy” funding will provide local governments with the resources they need to engage in strategic planning (with partners such as the Center for Public Leadership and Governance at the School of Government).

With respect to affordable housing development, it is advisable for local governments to collect and analyze housing data in order to inform local decision-making. A good start involves evaluating community housing needs, analyzing housing infrastructure, and anticipating future housing supply based on an understanding of the private market’s capacity to produce housing. It also requires communicating with public and private stakeholders, identifying suitable development sites, conducting market analysis, and creating housing development programs that are financially feasible and grounded in market realities. Given the uniqueness of this moment, most local governments probably don’t possess the staff capacity and skillsets to conduct the necessary analysis and implement the selected strategies for such a large amount of funding. Consider enlisting the help of regional councils of government (COGs), which have experience with managing federal grants, and seek assistance from public-minded development experts such as the Development Finance Initiative (DFI) at the School of Government.

Armed with housing data and market analysis, an understanding of the community’s needs, and feasible development plans grounded in market realities, local government leaders will be prepared to employ FRF to maximum effect.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.