Community development organizations today are asked to do more with less. They are expected to foster collaboration, engage residents, and drive economic growth, all while navigating shrinking budgets and rising needs. In this landscape, financial resources and technical expertise are essential, but another, less visible resource often makes the difference between success and stagnation: social capital.

In my recent bulletin, Breaking Down Social Capital: What Is It and What Does It Mean for Community Development Organizations? (UNC School of Government, July 2025), I explore the dimensions, types, and challenges of social capital and how it can be leveraged to strengthen communities. This blog post distills some of the key takeaways for practitioners, policymakers, and nonprofit leaders seeking to harness this vital, but sometimes overlooked resource.

What Do We Mean by Social Capital?

At its core, social capital is about relationships, trust, and shared norms. It is the connective tissue that allows people and organizations to access opportunities, solve problems, and build resilient neighborhoods. Unlike financial capital, which can be measured in dollars, or physical capital, which can be seen in infrastructure, social capital is intangible—but no less powerful.

In practice, social capital shapes how resources flow, how partners engage, and how initiatives scale. A city official who learns about a grant before it is widely announced, thanks to her strong relationships, is tapping into social capital. A nonprofit that secures volunteers and in-kind donations through longstanding partnerships is doing the same.

The Three Building Blocks of Social Capital

To understand social capital, it helps to break it into three types, each serving a unique function:

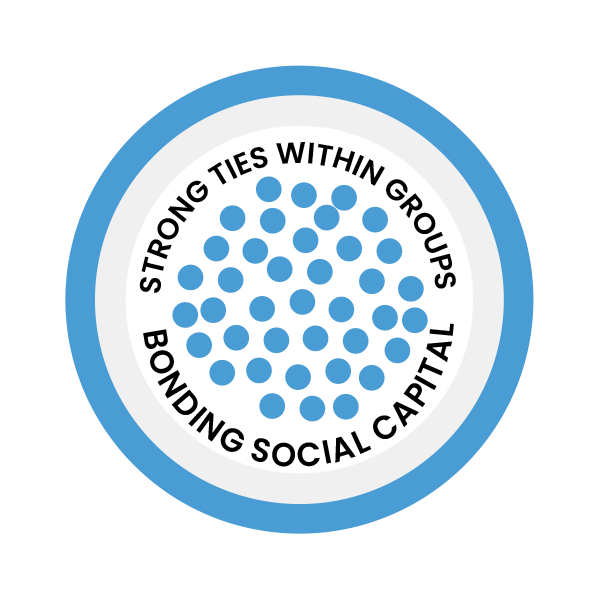

1. Bonding Social Capital – Strong ties within close-knit groups such as neighborhood associations or longstanding coalitions. This form fosters solidarity and mutual support, but it can also risk insularity.

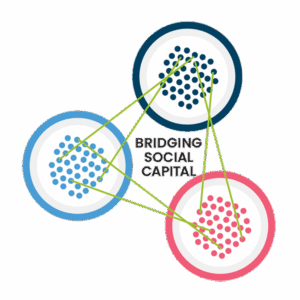

2. Bridging Social Capital – Connections that span across differences in demographics, class, or sector. These ties drive innovation, bring in fresh perspectives, and help organizations see beyond their immediate circles.

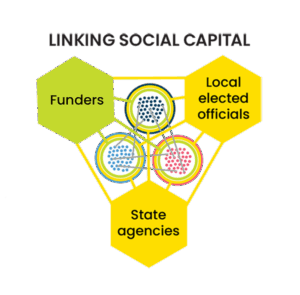

3. Linking Social Capital – Vertical relationships with funders, government agencies, or elected officials. Linking capital opens doors to power and resources that grassroots organizations might otherwise be unable to access.

All three forms of social capital are necessary in community organizations. Bonding provides stability, bridging fosters creativity, and linking expands influence.

Social Capital at Different Levels

Social capital does not exist in a vacuum; it operates at three interdependent levels.

Social capital does not exist in a vacuum; it operates at three interdependent levels.

- Individual Level: Relationships between people shape opportunities. For example, a grants coordinator with strong state-level connections might learn about funding opportunities before others.

- Organizational Level: Partnerships between institutions, such as a city department and a nonprofit food pantry, can lead to greater resilience, especially during times of crisis.

- Community Level: At this scale, informal interactions and collective action build the foundation for broader trust and shared progress, as seen when business owners and city officials co-design voluntary code compliance programs.

Recognizing which level is at play helps practitioners identify whether social capital is benefiting a single individual, one organization, or an entire community.

From Access to Action: How Social Capital Works

Social capital shows up in three distinct ways:

Social capital shows up in three distinct ways:

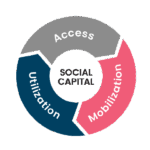

- Access – Who gets invited into the room? Access determines who benefits from grants, partnerships, and decision-making opportunities.

- Mobilization – How do networks activate in real time? For example, after a natural disaster, businesses and nonprofits may pool resources to help storefronts reopen quickly.

- Utilization – How are relationships converted into sustained outcomes? Long-term investments, such as storefront revitalization programs, demonstrate the strategic use of social capital.

These distinct forms demonstrate that social capital is not a static concept. It requires ongoing cultivation to deliver results.

The Challenges of Social Capital

Despite its benefits, social capital comes with its own set of complications. Some of the key challenges include:

- Exclusion: Those without existing connections may be excluded from opportunities.

- Overreliance on Informal Ties: Trust-based shortcuts can undermine transparency and accountability.

- Groupthink: Tight networks may resist new ideas or overlook dissenting voices.

- Dependency: When relationships hinge on one charismatic leader, networks can falter if those individual leaves.

Acknowledging these pitfalls allows organizations to build networks that are not only strong but also inclusive, adaptable, and sustainable.

Why This Matters?

Social capital is more than a buzzword. It shapes who gets access to resources, how partnerships function, and whether initiatives succeed or falter. For community development organizations, intentionally building and managing social capital can mean the difference between fragmented efforts and transformative change.

My recent bulletin provides a framework for understanding the types, levels, and challenges of social capital, while offering practical tools to help leaders strengthen resilience and build more connected communities.

Teshanee Williams is a School of Government faculty member focusing on nonprofit management, partnerships between nonprofits and local governments, and community engagement.