|

|

Student Corner: The Community Reinvestment Act & LIHTC: How changes in the banking sector could affect affordable housingBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished October 3, 2019

The policy is unique because few developers actually use these credits themselves, instead opting to sell them to investors to help finance construction. As a result, changes in demand for these credits can sometimes affect the financial viability of affordable housing projects. Who invests in LIHTC? Because affordable developments don’t generate substantial revenue, investors instead use the credits to reduce their tax liability. Since the 1990’s, large, publicly traded financial corporations have become the largest investors in housing credits. According to one report, approximately 85% of all housing credits are purchased by banks. Housing credits are appealing to banks for a number of reasons. Because bank profits are relatively stable year to year, they have a consistent need to reduce their tax burden. Housing credits are also safe assets for banks that are barred from making unnecessarily risky investments. Nationally, LIHTC units have higher occupancy rates and lower foreclosure rates than traditional multi-family housing. Banks are also bound by federal law to make investments and loans in communities where they draw deposits. This law, called the Community Reinvestment Act, plays an important role in the development of affordable housing, because it drives banks to fund development by purchasing housing credits. What is the CRA? In 1977, Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) to address decades of lending discrimination in minority communities. This practice, called redlining, prevented many minority households from accessing long-term, affordable mortgages that were being subsidized for white homeowners. CRA requires banks to meet a series of tests in areas where they collect deposits. Because deposits are used to generate loans, federal regulation requires banks to recirculate some of those loans in those communities. Banks can be tested on the number of local loans or investments, as well as the number of branches opened or closed. Assessment areas are generally communities where banks have a headquarters, satellite branches, deposit-collecting ATMs, or where most of their loans are made. The largest banks, which have locations all over the country, often have hundreds of CRA assessment areas. In return for passing these tests, a favorable CRA score will be taken into consideration when banks seek government approval to change their charters, merge, or acquire other banks. Both community advocates and banks believe the law can be changed to better reflect changes in the banking industry, but disagree on the difficulty of the tests. Relationship between CRA & LIHTC Housing credits are rarely sold at a 1-to-1 value, and the price often fluctuates in response to investor demand. For example, after President Trump passed his tax reform bill in 2017, the corporate tax rate was cut from 35 to 21 percent. Suddenly corporations didn’t need as many tax credits, and the price of LIHTC dropped. For developers, that means less investment to cover the costs of construction. Some industry experts predict passage of Trump’s tax reform will reduce the supply of affordable units by nearly 235,000 over the next 10 years. When banks invest in affordable housing credits, they’re not only reducing their future tax liability, but also looking for opportunities to improve their CRA score. For affordable housing developers, this is why CRA assessment areas are so important. Banks are more likely to pay a higher price for credits in their CRA assessment areas than in areas where they have few to no branches. For example, a development in rural counties are more likely to sell $1 of LIHTC for $0.86 – $0.87, whereas a development in major cities could sell credits for $0.92. Subtle shifts in price can sometimes make or break a deal, or affect the affordability of the project’s rents. Where are North Carolina’s hot CRA markets? To determine where banks might pay higher prices for LIHTC, let’s look at the number of bank branches by zip code. This analysis mirrors a similar study conducted by CohnReznick in 2013. Because large banks are more likely to need regulatory approval to merge or acquire smaller banks, the following map only includes branches of the 20 largest banks, such as Bank of America or BB&T. Unsurprisingly, the zip codes with the largest number of branches from the top 20 banks are located around North Carolina’s major metropolitan centers: Charlotte, Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro, and Wilmington. Here are the zip codes with 10 or more bank branches: What conclusions can be drawn from this trend? It shows that demand for housing credit doesn’t necessarily align with areas that have the greatest need for affordable housing. While all metropolitan areas are certainly in a housing crisis, North Carolina’s rural communities are also in desperate need of low-cost rental units. But because banks’ CRA obligations are so tightly confined to large urban centers, developers are less likely to sell credits at a price to make the project financially feasible. That tension is partly reflected when the LIHTC units are overlaid on the map. Like active CRA markets, LIHTC projects are heavily concentrated in urban areas. The imbalance in housing credit demand between urban and rural markets is likely to grow over time. For years, banks have shuttered branches in low-income, rural areas, and expanded in high-income, urban communities. As this trend continues, banks’ CRA obligations will shrink in communities most in need of affordable housing. As one study put it: “The banking sector’s demand for housing credit investment is not proportionately aligned with the location of housing credit properties. This has led to a phenomenon of overlapping CRA assessment areas in highly populated markets. As a result, investment test tends to drive capital to highly competitive areas that may result in disproportionately small number of available investment opportunities.” Other things to consider Of course, the CRA is not the only thing driving development of affordable housing. Other factors contribute to the favorability of urban areas besides the concentration of depositors. Cities are more likely to have higher incomes than rural communities, which allow developers to charge higher rents (while still maintaining affordability) to make debt payments and pay for operating expenses. The NCHFA also influences the location of LIHTC units through its Qualified Allocation Plan, which requires LIHTC units to be within a certain distance from grocery stores or pharmacies. Nevertheless, the relationship between LIHTC and the banking industry is an important, nuanced piece of affordable housing policy. As LIHTC continues to be the primary tool for creating low-income rental units, broad changes in the banking industry could affect the viability of the program. Frank Muraca is a master’s student in the UNC Department of City and Regional Planning and a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. He specializes in housing and community development, and researches issues related to housing finance and natural hazards.

|

Published October 3, 2019 By CED Program Interns & Students

Over the past few decades, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) has become the nation’s most important policy to incentivize the creation of affordable housing. LIHTC, administered in North Carolina through the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency, allocates credits to private developers who then produce affordable units. Since its inception, LIHTC has helped create an estimated 2.3 million homes.

Over the past few decades, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) has become the nation’s most important policy to incentivize the creation of affordable housing. LIHTC, administered in North Carolina through the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency, allocates credits to private developers who then produce affordable units. Since its inception, LIHTC has helped create an estimated 2.3 million homes.

The policy is unique because few developers actually use these credits themselves, instead opting to sell them to investors to help finance construction. As a result, changes in demand for these credits can sometimes affect the financial viability of affordable housing projects.

Who invests in LIHTC? Because affordable developments don’t generate substantial revenue, investors instead use the credits to reduce their tax liability. Since the 1990’s, large, publicly traded financial corporations have become the largest investors in housing credits. According to one report, approximately 85% of all housing credits are purchased by banks.

Housing credits are appealing to banks for a number of reasons. Because bank profits are relatively stable year to year, they have a consistent need to reduce their tax burden. Housing credits are also safe assets for banks that are barred from making unnecessarily risky investments. Nationally, LIHTC units have higher occupancy rates and lower foreclosure rates than traditional multi-family housing.

Banks are also bound by federal law to make investments and loans in communities where they draw deposits. This law, called the Community Reinvestment Act, plays an important role in the development of affordable housing, because it drives banks to fund development by purchasing housing credits.

What is the CRA?

In 1977, Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) to address decades of lending discrimination in minority communities. This practice, called redlining, prevented many minority households from accessing long-term, affordable mortgages that were being subsidized for white homeowners.

CRA requires banks to meet a series of tests in areas where they collect deposits. Because deposits are used to generate loans, federal regulation requires banks to recirculate some of those loans in those communities. Banks can be tested on the number of local loans or investments, as well as the number of branches opened or closed. Assessment areas are generally communities where banks have a headquarters, satellite branches, deposit-collecting ATMs, or where most of their loans are made. The largest banks, which have locations all over the country, often have hundreds of CRA assessment areas.

In return for passing these tests, a favorable CRA score will be taken into consideration when banks seek government approval to change their charters, merge, or acquire other banks. Both community advocates and banks believe the law can be changed to better reflect changes in the banking industry, but disagree on the difficulty of the tests.

Relationship between CRA & LIHTC

Housing credits are rarely sold at a 1-to-1 value, and the price often fluctuates in response to investor demand. For example, after President Trump passed his tax reform bill in 2017, the corporate tax rate was cut from 35 to 21 percent. Suddenly corporations didn’t need as many tax credits, and the price of LIHTC dropped. For developers, that means less investment to cover the costs of construction. Some industry experts predict passage of Trump’s tax reform will reduce the supply of affordable units by nearly 235,000 over the next 10 years.

When banks invest in affordable housing credits, they’re not only reducing their future tax liability, but also looking for opportunities to improve their CRA score. For affordable housing developers, this is why CRA assessment areas are so important. Banks are more likely to pay a higher price for credits in their CRA assessment areas than in areas where they have few to no branches. For example, a development in rural counties are more likely to sell $1 of LIHTC for $0.86 – $0.87, whereas a development in major cities could sell credits for $0.92. Subtle shifts in price can sometimes make or break a deal, or affect the affordability of the project’s rents.

Where are North Carolina’s hot CRA markets?

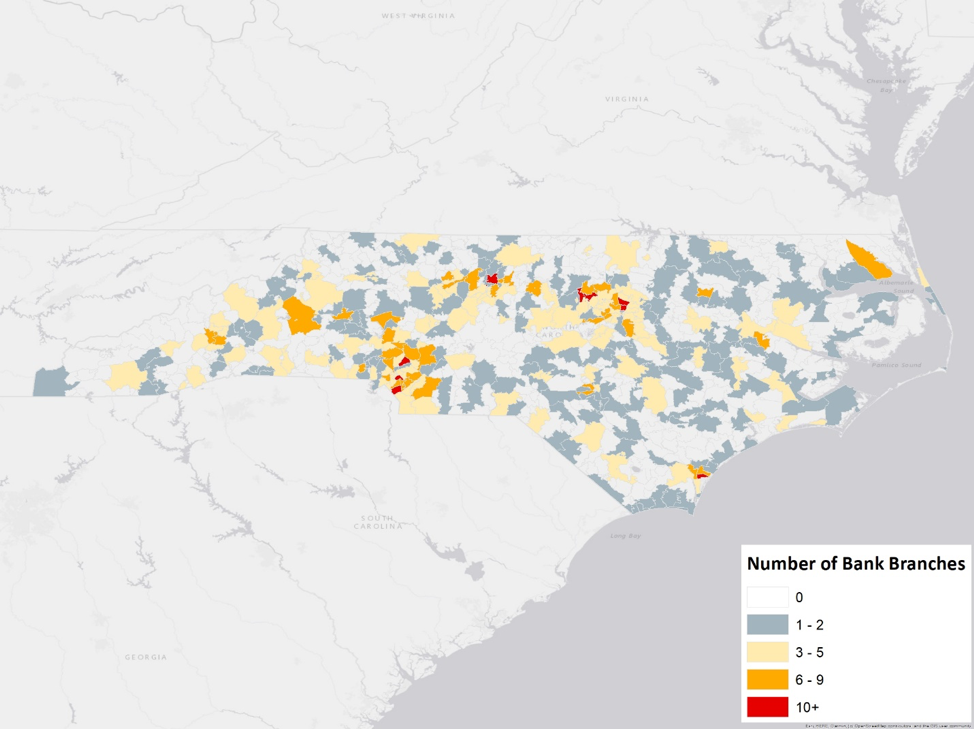

To determine where banks might pay higher prices for LIHTC, let’s look at the number of bank branches by zip code. This analysis mirrors a similar study conducted by CohnReznick in 2013. Because large banks are more likely to need regulatory approval to merge or acquire smaller banks, the following map only includes branches of the 20 largest banks, such as Bank of America or BB&T.

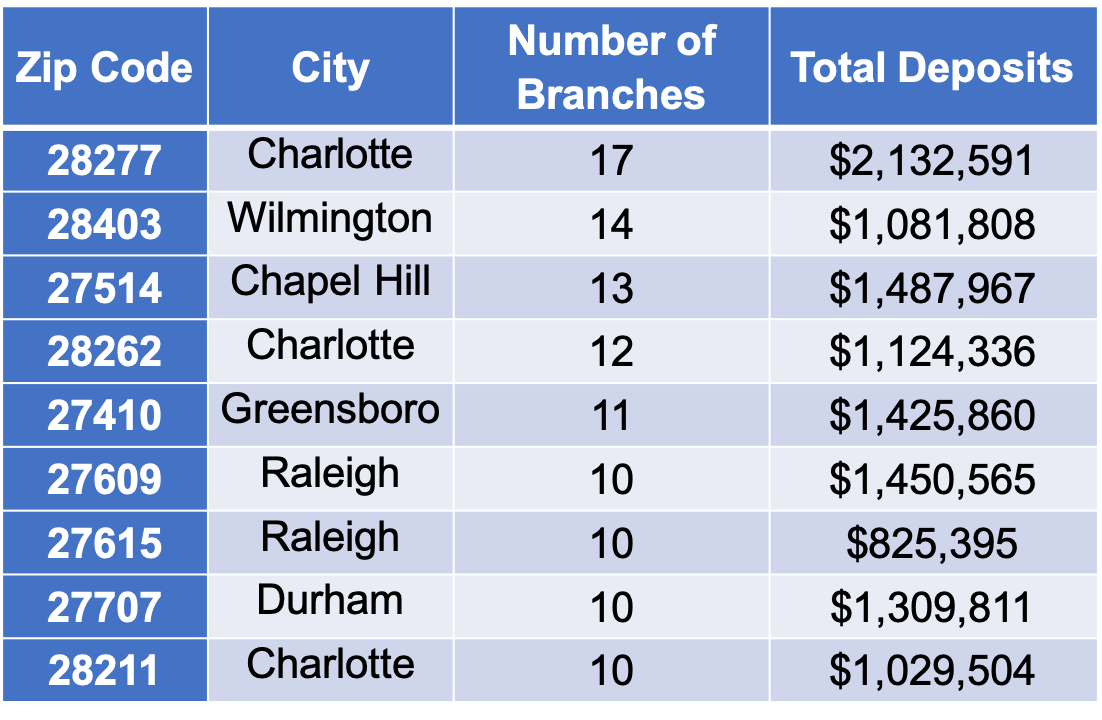

Unsurprisingly, the zip codes with the largest number of branches from the top 20 banks are located around North Carolina’s major metropolitan centers: Charlotte, Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro, and Wilmington. Here are the zip codes with 10 or more bank branches:

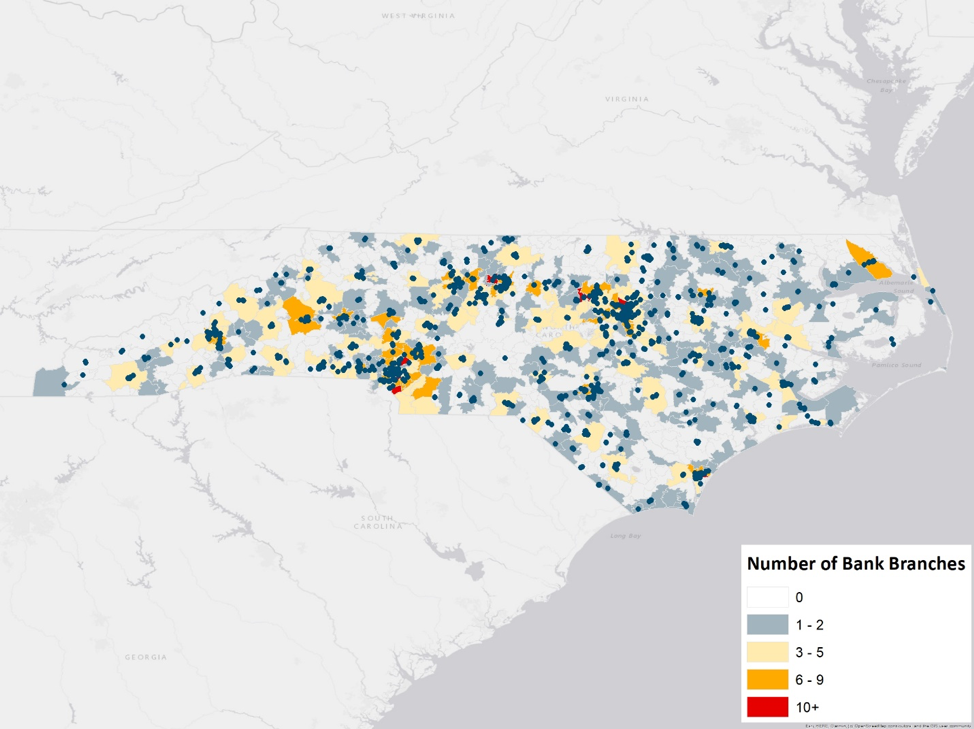

What conclusions can be drawn from this trend? It shows that demand for housing credit doesn’t necessarily align with areas that have the greatest need for affordable housing. While all metropolitan areas are certainly in a housing crisis, North Carolina’s rural communities are also in desperate need of low-cost rental units. But because banks’ CRA obligations are so tightly confined to large urban centers, developers are less likely to sell credits at a price to make the project financially feasible. That tension is partly reflected when the LIHTC units are overlaid on the map. Like active CRA markets, LIHTC projects are heavily concentrated in urban areas.

The imbalance in housing credit demand between urban and rural markets is likely to grow over time. For years, banks have shuttered branches in low-income, rural areas, and expanded in high-income, urban communities. As this trend continues, banks’ CRA obligations will shrink in communities most in need of affordable housing. As one study put it: “The banking sector’s demand for housing credit investment is not proportionately aligned with the location of housing credit properties. This has led to a phenomenon of overlapping CRA assessment areas in highly populated markets. As a result, investment test tends to drive capital to highly competitive areas that may result in disproportionately small number of available investment opportunities.”

Other things to consider

Of course, the CRA is not the only thing driving development of affordable housing. Other factors contribute to the favorability of urban areas besides the concentration of depositors. Cities are more likely to have higher incomes than rural communities, which allow developers to charge higher rents (while still maintaining affordability) to make debt payments and pay for operating expenses. The NCHFA also influences the location of LIHTC units through its Qualified Allocation Plan, which requires LIHTC units to be within a certain distance from grocery stores or pharmacies.

Nevertheless, the relationship between LIHTC and the banking industry is an important, nuanced piece of affordable housing policy. As LIHTC continues to be the primary tool for creating low-income rental units, broad changes in the banking industry could affect the viability of the program.

Frank Muraca is a master’s student in the UNC Department of City and Regional Planning and a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. He specializes in housing and community development, and researches issues related to housing finance and natural hazards.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.