|

|

The NC Workforce of Tomorrow: the Condition of Community College Students TodayBy Maureen BernerPublished January 21, 2020The students at community college today represent the workforce available tomorrow. If they are in trouble, it is a major red flag for CED professionals. CED professionals need to understand the world of community college students if they are to help them develop into the workforce in the next ten years, attracting business and investment ready to tap into its potential. A growing body of data suggest the students are deep in trouble. The community college system in North Carolina is a backbone for community development. They support CED efforts in all 100 counties through 58 individual community colleges, with targeted economic development efforts through programs such as the ApprenticeNC and Small Business Center. They serve over a half a million students of all ages and are considered a vital gateway to jobs. New data are emerging around one important indicator of economic condition of these soon-to-be-members-of-the-North-Carolina-workforce: food insecurity. Food security reflects access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. If someone does not have that access, they are considered food insecure. Food insecurity is such a basic indicator because it directly measures the ability of individuals and families to put healthy food on the table on a regular basis. Since food is flexible day to day, food security/insecurity is a real-time view on whether or not you can make ends meet, day in and day out—or does someone need to skip breakfast or lunch, worry about getting groceries for the kids at the end of the month, or visit a food pantry? A number of new studies are coming out that reflect the problem at community colleges nationally. The most extensive, a national study with tens of thousands of respondents, is part of a larger effort from the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University, which published a major report, College and Universi ty Basic Needs Insecurity, this past year. They focused on both food and housing insecurity. The findings are important for CED professionals who are seeking to create jobs in their communities because it speaks to the potential quality and readiness of that workforce. Surprisingly, the Temple researchers found less than half of two-year students are food secure. When also considering housing insecurity, the percent of two-year students who are food and housing secure is only 30%. In other words, 70 percent of students at two-year institutions are living on the edge of having enough food or reliable housing. Four-year college students are not far behind their community college counterparts. What do students do in this situation? The figure below compares several of the main coping strategies from two- and four-year institutions. They clearly have implications for the students’ prospects for success. Business professionals know that quality parts make for a quality product. As CED professionals consider how to make job training, placement, retention, and skill-building programs successful, they may wish to consider the condition of the students in those programs, and how investment in creating a stable situation for them at home will mean better worker, and therefore business, outcomes in the end. |

Published January 21, 2020 By Maureen Berner

The students at community college today represent the workforce available tomorrow. If they are in trouble, it is a major red flag for CED professionals. CED professionals need to understand the world of community college students if they are to help them develop into the workforce in the next ten years, attracting business and investment ready to tap into its potential. A growing body of data suggest the students are deep in trouble.

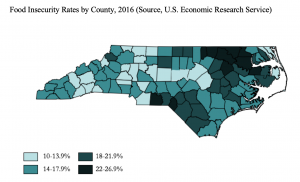

The community college system in North Carolina is a backbone for community development. They support CED efforts in all 100 counties through 58 individual community colleges, with targeted economic development efforts through programs such as the ApprenticeNC and Small Business Center. They serve over a half a million students of all ages and are considered a vital gateway to jobs.

New data are emerging around one important indicator of economic condition of these soon-to-be-members-of-the-North-Carolina-workforce: food insecurity. Food security reflects access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life. If someone does not have that access, they are considered food insecure. Food insecurity is such a basic indicator because it directly measures the ability of individuals and families to put healthy food on the table on a regular basis. Since food is flexible day to day, food security/insecurity is a real-time view on whether or not you can make ends meet, day in and day out—or does someone need to skip breakfast or lunch, worry about getting groceries for the kids at the end of the month, or visit a food pantry?

A number of new studies are coming out that reflect the problem at community colleges nationally. The most extensive, a national study with tens of thousands of respondents, is part of a larger effort from the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University, which published a major report, College and Universi

ty Basic Needs Insecurity, this past year. They focused on both food and housing insecurity. The findings are important for CED professionals who are seeking to create jobs in their communities because it speaks to the potential quality and readiness of that workforce.

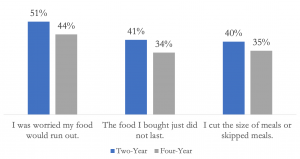

Surprisingly, the Temple researchers found less than half of two-year students are food secure. When also considering housing insecurity, the percent of two-year students who are food and housing secure is only 30%. In other words, 70 percent of students at two-year institutions are living on the edge of having enough food or reliable housing. Four-year college students are not far behind their community college counterparts.

What do students do in this situation? The figure below compares several of the main coping strategies from two- and four-year institutions. They clearly have implications for the students’ prospects for success.

Business professionals know that quality parts make for a quality product. As CED professionals consider how to make job training, placement, retention, and skill-building programs successful, they may wish to consider the condition of the students in those programs, and how investment in creating a stable situation for them at home will mean better worker, and therefore business, outcomes in the end.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.

One Response to “The NC Workforce of Tomorrow: the Condition of Community College Students Today”

Tim Moore

As a community (county) college graduate myself – who then want on to earn both BS and M.Ed. (in industrial career counseling) degrees and spend almost 3 decades in employment & training, HRD, workforce/talent development, and higher education (often working with disadvantaged, first-generation students), I can attest to this maybe not-so-obvious but also very clear basic needs security gap for p-20 students, their parents, and even many workers. As Maslow stated, physiological (e.g., food), safety (e.g., housing) needs must be met before humans can get to developing things like a sense of belonging, esteem, and self-actualization (i.e., education leading to a successful and meaningful occupation/career and life). One way that we can all help ‘students’ – perhaps at least beginning in high school and continuing thru higher education/training in adult hood – is to offer not just supportive services (e.g., free/reduced cost meals, campus food banks, Finish Line Grants, etc.) but also paid experiential education/training opportunities such as co-op, internships, and apprenticeships so folks can earn while they learn (in addition perhaps to financial aid and work-study). There are also ways to help turn even minimum wage off-campus jobs into better work-based learning experiences benefitting both the students and employers. Hungry, insecure, tired, stressed and worried people do not make the best p-20 students, trainees, or employees. We simply must find and launch ways to provide for basic needs of our populace including affordable housing (perhaps community college dorms) and healthy food, etc. for our communities for equitable economic, workforce, and neighborhood development and better business outcomes and ROI. And Kudos to Temple U. both my parents’ alma mater for shedding additional light on this ‘hiding in plain sight’ issue.