|

|

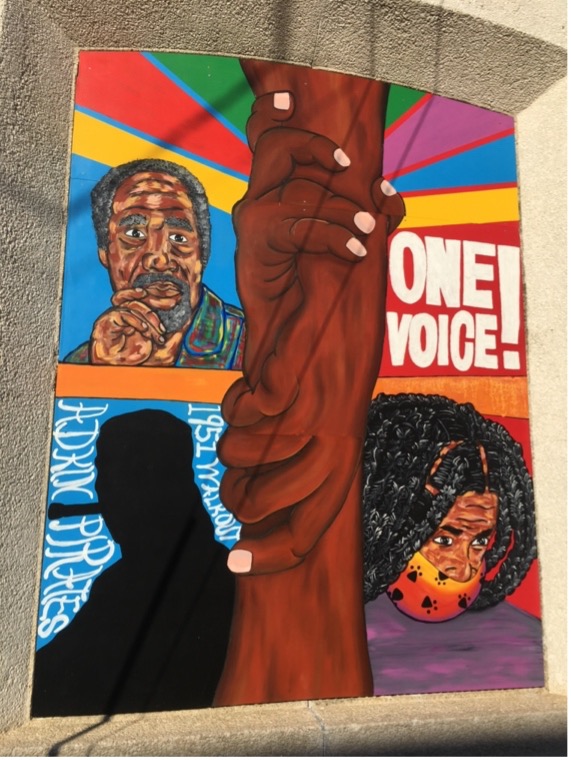

Creating a Public Mural Program – Lessons from Kinston, NC (Part 1)By CED Guest AuthorPublished May 3, 2021In the Fall of 2019, the City of Kinston established the Downtown Kinston Mural Program, a public art initiative that uses creative placemaking to build Kinston’s reputation as a destination for unique, thought-provoking art and community-oriented artists. This three-part blog post series outlines Kinston’s experience and important takeaways for future municipalities interested in starting their own mural programs, covering topics such as citizen involvement, artist recruitment and selection, mural installation logistics, public engagement during a pandemic, unexpected costs, and more. Funding & Leadership

The City of Kinston’s primary source of funding was a $100,000 Our Town grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), but public art can be funded through other grants (Baltimore, MD), private donations (Sanford, NC), or annual budget allocations (Asheville, NC). However, programs should plan for at least $15,000 per mural and, depending on the maintenance agreement plan, $3,000 worth of maintenance costs per mural over a 10-year period. Kinston’s Mural Program was led by Planning Director Adam Short and Community Development Planner/Lead for North Carolina Fellow Sarah Arney, Marcia Perritt with the Development Finance Initiative (DFI), and a citizen Selection Committee. The program required at least two staff each working 10 hours a week working on grant management, program design, Committee facilitation, Council updates, research, logistics, community engagement, and budget management. Catherine Hart, an artist consultant who runs the Jersey City Mural Arts Youth Program, was an enormous asset during the program design process; her experience on both sides of art programs helped the City anticipate common needs and concerns from artists. The local Kinston Community Council for the Arts also advised. Program Design Prior to the involvement of the citizen Selection Committee, staff and consultants developed the basic outline of the program: The opportunity to host a mural was offered to property owners within Kinston’s downtown Municipal Service District (MSD), but not to properties that contributed to the historic district (a requirement by the NEA). Owners participated for free, but the Selection Committee and artist had creative freedom and were responsible for the mural design; the owner had the right to refuse the concept presented to them, but the program was not a commission. Once the mural was installed, the owner was required to keep the mural for at least five years. Artists were paid for their design, installation, and two community events with a negotiated fee based on their experience, the mural size, and design complexity. Artists were provided housing, heavy equipment, and insurance, but were required to cover their own materials, travel, and per diem expenses. The artist would retain full control over the mural image, and the City would not be able to profit off the sale of the mural image after the program. The City of Kinston assumed responsibility for the administration of the program and maintenance of the murals for at least five years after their installation, as outlined in an agreement with property owners.  Selection Committee Recruitment The Selection Committee was a citizen group that set the goals for the program, selected walls, approved artists and concepts, and advocated for the program. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are important for any public project, and they are crucial with respect to public art, especially when creating the committee that drives the process. At the surface level, the Mural Program would quite literally change the face of the city for the next five years— staff wanted to ensure that the mural concepts resonated with and represented the local community. Additionally, staff wanted to reinforce Kinston’s image as a creative community with a burgeoning arts scene, in turn bringing visitors to downtown and stimulating economic growth. The program also hoped to use public art to spark dialogue around social justice issues and community concerns, and to celebrate the history, art, and regional authenticity that makes Kinston special. To reach these lofty goals required three things:

With these components in mind, staff used a variety of methods to identify members of the Selection Committee:

All Selection Committee members were required to formally apply for the Committee, even if they were initially invited to apply or recommended by Council. The application form outlined the expectations for committee membership, set standards around conflicts of interest, and asked applicants about their identities, occupation, interest in public art, and how they participate in groups. The City received 25 online applications from local residents for the Committee. Ultimately, the application information helped staff ensure that the Selection Committee represented the diversity of the Kinston community with regard to age, race/ethnicity, and occupation. The initial 14-member Selection Committee included representatives from the local and state arts council, public school system, nonprofit sector, African American Heritage Commission, local artists, local churches, environmental organizations, community activists, and downtown property owners. Two City Council members also participated in Committee meetings.  Selection Committee Meetings Accessible meetings are an important element of a successful, inclusive Committee. Neither diversity nor equity matter very much if the people involved cannot attend meetings or don’t feel welcome. Staff scheduled meetings in the evening, provided food (when in person), met in ADA accessible locations, and offered technical support for scheduling and virtual participation once COVID-19 struck. In the Selection Committee’s first meeting, they set a pattern for the group that encouraged fun alongside hard work and meaningful discussion, including:

COVID-19 shut down in-person meetings in early March, just when the Committee was set to begin selecting artists, arguably the most challenging and time-intensive task in the process. Thankfully, the Committee had established a good foundation, but the change to all-virtual meetings required members to become comfortable with remote technology to remain active participants. Staff tried to mitigate this challenge by encouraging members to call in if they didn’t have a camera, and sending artist profiles by postal mail prior to meetings. An upside of virtual meetings was the committee could have more frequent, shorter meetings for time-sensitive decisions and easily bring in out-of-town artists for a virtual concept review.  Wall Selection The Selection Committee’s first major task was to select walls for the program. Staff did upfront prep work to gather a list of potential walls by advertising the opportunity in the paper/social media and conducting a “windshield survey” of MSD walls based on the criteria below. Staff then reached out to owners to determine their interest. Interested owners were required to complete part one of a two part owner permission form (part two was signed after the concept was approved by the owner) to demonstrate their commitment and understanding of the program parameters. The Selection Committee curated a portfolio of eight walls based on the following criteria:

Read Part 2 of this series here, which focuses on the process for recruiting and selecting artists, and pairing artists with walls. This post was co-authored by Sarah Arney, Lead for NC Fellow with the City of Kinston, and Marcia Perritt, Associate Director with the UNC Development Finance Initiative. |

Published May 3, 2021 By CED Guest Author

In the Fall of 2019, the City of Kinston established the Downtown Kinston Mural Program, a public art initiative that uses creative placemaking to build Kinston’s reputation as a destination for unique, thought-provoking art and community-oriented artists. This three-part blog post series outlines Kinston’s experience and important takeaways for future municipalities interested in starting their own mural programs, covering topics such as citizen involvement, artist recruitment and selection, mural installation logistics, public engagement during a pandemic, unexpected costs, and more.

Funding & Leadership

The City of Kinston’s primary source of funding was a $100,000 Our Town grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), but public art can be funded through other grants (Baltimore, MD), private donations (Sanford, NC), or annual budget allocations (Asheville, NC). However, programs should plan for at least $15,000 per mural and, depending on the maintenance agreement plan, $3,000 worth of maintenance costs per mural over a 10-year period.

Kinston’s Mural Program was led by Planning Director Adam Short and Community Development Planner/Lead for North Carolina Fellow Sarah Arney, Marcia Perritt with the Development Finance Initiative (DFI), and a citizen Selection Committee. The program required at least two staff each working 10 hours a week working on grant management, program design, Committee facilitation, Council updates, research, logistics, community engagement, and budget management. Catherine Hart, an artist consultant who runs the Jersey City Mural Arts Youth Program, was an enormous asset during the program design process; her experience on both sides of art programs helped the City anticipate common needs and concerns from artists. The local Kinston Community Council for the Arts also advised.

Program Design

Prior to the involvement of the citizen Selection Committee, staff and consultants developed the basic outline of the program:

The opportunity to host a mural was offered to property owners within Kinston’s downtown Municipal Service District (MSD), but not to properties that contributed to the historic district (a requirement by the NEA). Owners participated for free, but the Selection Committee and artist had creative freedom and were responsible for the mural design; the owner had the right to refuse the concept presented to them, but the program was not a commission. Once the mural was installed, the owner was required to keep the mural for at least five years.

Artists were paid for their design, installation, and two community events with a negotiated fee based on their experience, the mural size, and design complexity. Artists were provided housing, heavy equipment, and insurance, but were required to cover their own materials, travel, and per diem expenses. The artist would retain full control over the mural image, and the City would not be able to profit off the sale of the mural image after the program. The City of Kinston assumed responsibility for the administration of the program and maintenance of the murals for at least five years after their installation, as outlined in an agreement with property owners.

Selection Committee Recruitment

The Selection Committee was a citizen group that set the goals for the program, selected walls, approved artists and concepts, and advocated for the program. Diversity, equity, and inclusion are important for any public project, and they are crucial with respect to public art, especially when creating the committee that drives the process.

At the surface level, the Mural Program would quite literally change the face of the city for the next five years— staff wanted to ensure that the mural concepts resonated with and represented the local community. Additionally, staff wanted to reinforce Kinston’s image as a creative community with a burgeoning arts scene, in turn bringing visitors to downtown and stimulating economic growth. The program also hoped to use public art to spark dialogue around social justice issues and community concerns, and to celebrate the history, art, and regional authenticity that makes Kinston special. To reach these lofty goals required three things:

- A variety of identities, experiences, and ways of thinking about the world— demographic, experiential, and cognitive diversity

- Priority given to citizens usually absent or excluded from public art—equity for people of color (POC) and young people in public art.

- True authority given to citizens over the program. This concept is evidenced best by Arnstein’s ladder of participation, which demonstrates that the more control citizens have over the process, the more governments communicate confidence in their citizens and the more buy-in from the community.

With these components in mind, staff used a variety of methods to identify members of the Selection Committee:

- Staff relied on existing networks, such as recommendations from elected officials and community leaders and inviting a limited number of members of complementary boards/committees to participate.

- Staff focused the majority of its efforts on recruiting committee members who weren’t already well-represented on other boards in order to cultivate more civic engagement. Staff made “cold calls” to community members that didn’t typically participate in local civic, government, or arts advisory committees to avoid the “Usual Suspects”. However, staff also used the usual citizen representatives as an asset, asking them to think of people in their network who would be interested, but had not participated in committees like this before—often it took several asks before a “usual suspect” was able to think of a person who was truly new to the process.

- There was also an open call for applicants to the general public through press release, social media, and repeated open invitations at Council meetings.

All Selection Committee members were required to formally apply for the Committee, even if they were initially invited to apply or recommended by Council. The application form outlined the expectations for committee membership, set standards around conflicts of interest, and asked applicants about their identities, occupation, interest in public art, and how they participate in groups. The City received 25 online applications from local residents for the Committee. Ultimately, the application information helped staff ensure that the Selection Committee represented the diversity of the Kinston community with regard to age, race/ethnicity, and occupation. The initial 14-member Selection Committee included representatives from the local and state arts council, public school system, nonprofit sector, African American Heritage Commission, local artists, local churches, environmental organizations, community activists, and downtown property owners. Two City Council members also participated in Committee meetings.

Selection Committee Meetings

Accessible meetings are an important element of a successful, inclusive Committee. Neither diversity nor equity matter very much if the people involved cannot attend meetings or don’t feel welcome. Staff scheduled meetings in the evening, provided food (when in person), met in ADA accessible locations, and offered technical support for scheduling and virtual participation once COVID-19 struck. In the Selection Committee’s first meeting, they set a pattern for the group that encouraged fun alongside hard work and meaningful discussion, including:

- Setting the stage for the meeting with a recap and objectives—the facilitator focused on providing information and structure, keeping members up to date regardless of their prior participation and requiring group buy-in before moving on from a decision.

- Focusing the meeting around 1-2 decisions—the facilitator presented a manageable number of decisions that could be discussed and concluded before the end of the meeting.

- Ending on time with appreciation, accomplishments, and action items—avoid burn out by ending on time, regularly thanking members in meetings and in public, and giving limited, clear instructions for homework when necessary.

COVID-19 shut down in-person meetings in early March, just when the Committee was set to begin selecting artists, arguably the most challenging and time-intensive task in the process. Thankfully, the Committee had established a good foundation, but the change to all-virtual meetings required members to become comfortable with remote technology to remain active participants. Staff tried to mitigate this challenge by encouraging members to call in if they didn’t have a camera, and sending artist profiles by postal mail prior to meetings. An upside of virtual meetings was the committee could have more frequent, shorter meetings for time-sensitive decisions and easily bring in out-of-town artists for a virtual concept review.

Wall Selection

The Selection Committee’s first major task was to select walls for the program. Staff did upfront prep work to gather a list of potential walls by advertising the opportunity in the paper/social media and conducting a “windshield survey” of MSD walls based on the criteria below. Staff then reached out to owners to determine their interest. Interested owners were required to complete part one of a two part owner permission form (part two was signed after the concept was approved by the owner) to demonstrate their commitment and understanding of the program parameters. The Selection Committee curated a portfolio of eight walls based on the following criteria:

- Condition: free of water damage, cracks, crumbling mortar, existing paint, interfering wires, etc.

- *Artist consultant Catherine Hart was especially helpful here to anticipate possible problems with the walls. Condition also ended up significantly affecting the cost the wall preparation.

- Visibility and Location: highly visible while driving or walking, along key “gateways” into the City, areas of historical significance, as well as hidden “surprise” murals in unexpected or out-of-the-way locations

- Owner Cooperativeness: impressions of their interest in the program, ease of communication, openness to letting the artist and Committee lead development of the mural concept, with minimal owner input

- Budget Feasibility: size, coverage possible for the fee suggested

Read Part 2 of this series here, which focuses on the process for recruiting and selecting artists, and pairing artists with walls.

This post was co-authored by Sarah Arney, Lead for NC Fellow with the City of Kinston, and Marcia Perritt, Associate Director with the UNC Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.