|

|

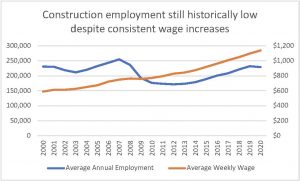

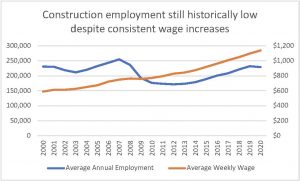

Student Corner: Addressing Construction Labor Shortages Post-PandemicBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished September 7, 2021Labor shortages are not new to the construction industry, but the pandemic has added fuel to an already urgent issue. With an aging workforce vulnerable to economic shocks, the construction industry has seen sharp rises and falls in the last 20 years, increasing safety and quality concerns. Since 2000, North Carolina has seen a decline in total construction employees, despite steady increases in average weekly wages (shown in the table below). The pandemic stalled employment growth and demand temporarily, but recently demand has been rising again, especially in new residential development and rehabilitation, with many North Carolina construction businesses looking to hire multiple new employees.

Labor availability has long been a key challenge in surveys of construction employers such as the National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo Housing Market Index. Many specialized trade workers, such as electricians, are aging. According to Tim Norman, Head of the N.C. State Board of Examiners for electricians, in 2019 over 70% of the 13,000 licensed electricians in the state were 51 or older and less than 1% were under the age of 30. Additionally, many construction companies point to a generational shift in how construction is perceived, as the last two decades have seen increasing focus on 4-year college degrees. With less young individuals entering the industry, the median age of construction workers across the United States has risen, prompting the creation of numerous workforce development initiatives at local, state, and federal levels aimed at bringing younger generations into the industry. With the pandemic causing mass layoffs, there was some thought that labor shortages would be less of an issue following recovery. However, according to an analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey by Marcum, the current proportion of available construction jobs is still high compared to jobs available between 2008 and 2017. As of July 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that there are 300,000 unfilled construction jobs nationwide. It is important to note that the construction industry is broad, including specialized trade workers, project managers, and construction laborers who often do the most physical tasks. The persistence of labor shortages post-pandemic likely has varying causes. One possibility is that construction workers laid off during the pandemic retired or left the industry, mirroring the actions of many construction workers after the Great Recession. Others might have found themselves in the position to retire early. Some construction companies say the unemployment benefits provided by the federal government incentivize not returning to work, although research, most recently from the Federal Reserve of San Francisco, has shown that is only one small factor impacting the job-finding rate. Other potential causes of a continued labor shortage post-pandemic relate to the factors long seen as issues in recruitment. This includes a perception of low wages for all construction workers, the cyclical nature of construction employment, the lack of employer healthcare available to many construction workers, and other image issues stopping unemployed workers from joining the construction industry. There is also a significant gender disparity in construction employment – according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2020 only about 11% of the construction industry’s employees were women, despite making up about 47% of the nation’s workforce. According to Marcum’s analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey the average hourly wage nationally for construction workers in January 2021 was $32/hour, the highest it’s ever been. North Carolina is also seeing high construction worker wages, especially in areas like the Research Triangle and the Charlotte metropolitan area. According to our own interviews, this makes it more difficult for companies based in smaller counties to compete for potential employees in terms of wages. While raising wages remains a critical step towards recruiting new construction workers, other economic levers such as offering access to employer healthcare, paid vacation, and other benefits are also needed. Other than these economic incentives, many industry advocates say that to truly bridge the gap in the labor markets, we must reframe the conversation around construction, especially with youth. This requires investment in recruitment and training initiatives at the company, community, and federal level. Prior to the pandemic, there was some concern that a lack of training, combined with its expense, could be exacerbating labor shortages. The pandemic disrupted the operations and funding of many construction training programs, and it will be an important part of recovery efforts to revisit and reaffirm government support for those programs where possible.  In general, government can play three key roles in addressing the construction labor shortage: advocate, facilitator, and funder. As an advocate, government can help dispel longstanding myths about what construction jobs entail and what wage and entrepreneurial opportunities exist for the varying occupations. In interviews with local North Carolina organizations, government was seen as a critical partner in helping to validate a new narrative around construction work. As a facilitator, government can provide connections between existing initiatives and organize the wealth of resources available at the local, state, and federal level. In particular, government has the opportunity to facilitate conversations between organizations serving particular audiences such as women or veterans or workers who don’t speak English fluently, to other employers, workforce development boards, private companies, and even small business training centers. As a funder, there are many creative efforts underway to educate, train, and retain potential construction workers. At this moment, the American Rescue Plan funding offers the best opportunity for catalyzing new and successful programming around this issue. Governor Cooper’s ARP budget as of May 2021 includes $150 million “to ensure the development of a 21st century workforce through access to 21st century technology” and specifically calls out funding apprenticeships for high demand fields like construction. Apprenticeships are employer or industry-initiated ventures with their local community college and ApprenticeshipNC. At the time of writing, 25 registered building trades apprenticeships existed in North Carolina. To strengthen the foundations for a successful apprenticeship, government should continue to work closely with the NC community college system, as some may have capacity and desire to expand their building trades programs to meet increased demand, but they may not have the physical space or capital to fund that expansion. Additionally, feedback from construction employers on the ease of deciding to create a registered apprenticeship should be explored to continue to improve the process and add to the number of programs. Increased investments by government could also include more scholarships for certification and training, especially for underrepresented or nontraditional construction workers. While it is important to focus on youth engagement, the potential career trajectories of incumbent workers also must be taken into account. Lastly, government support can be helpful in various forms for the variety of activities companies and nonprofits may choose to promote, such as design/construction contests for youth, clubs/workshops for tools learning, or youth construction academies in partnership with the YMCA. Ultimately, addressing the labor shortage in construction, particularly with skilled trade workers, will take a coordinated effort to educate, recruit, and retain workers, requiring close interaction between companies, industry leaders, workforce development programs, schools, and government.

Many thanks to Zane Stokes, Farrah Pulliam, Jeff Parsons, and Devin Baucom for their time and conversations around this topic.

Marielle Saunders is a Master’s in City and Regional Planning candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill and a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. |

Published September 7, 2021 By CED Program Interns & Students

Labor shortages are not new to the construction industry, but the pandemic has added fuel to an already urgent issue. With an aging workforce vulnerable to economic shocks, the construction industry has seen sharp rises and falls in the last 20 years, increasing safety and quality concerns. Since 2000, North Carolina has seen a decline in total construction employees, despite steady increases in average weekly wages (shown in the table below). The pandemic stalled employment growth and demand temporarily, but recently demand has been rising again, especially in new residential development and rehabilitation, with many North Carolina construction businesses looking to hire multiple new employees.

Labor availability has long been a key challenge in surveys of construction employers such as the National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo Housing Market Index. Many specialized trade workers, such as electricians, are aging. According to Tim Norman, Head of the N.C. State Board of Examiners for electricians, in 2019 over 70% of the 13,000 licensed electricians in the state were 51 or older and less than 1% were under the age of 30. Additionally, many construction companies point to a generational shift in how construction is perceived, as the last two decades have seen increasing focus on 4-year college degrees. With less young individuals entering the industry, the median age of construction workers across the United States has risen, prompting the creation of numerous workforce development initiatives at local, state, and federal levels aimed at bringing younger generations into the industry.

With the pandemic causing mass layoffs, there was some thought that labor shortages would be less of an issue following recovery. However, according to an analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey by Marcum, the current proportion of available construction jobs is still high compared to jobs available between 2008 and 2017. As of July 2021, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that there are 300,000 unfilled construction jobs nationwide. It is important to note that the construction industry is broad, including specialized trade workers, project managers, and construction laborers who often do the most physical tasks.

The persistence of labor shortages post-pandemic likely has varying causes. One possibility is that construction workers laid off during the pandemic retired or left the industry, mirroring the actions of many construction workers after the Great Recession. Others might have found themselves in the position to retire early. Some construction companies say the unemployment benefits provided by the federal government incentivize not returning to work, although research, most recently from the Federal Reserve of San Francisco, has shown that is only one small factor impacting the job-finding rate.

Other potential causes of a continued labor shortage post-pandemic relate to the factors long seen as issues in recruitment. This includes a perception of low wages for all construction workers, the cyclical nature of construction employment, the lack of employer healthcare available to many construction workers, and other image issues stopping unemployed workers from joining the construction industry. There is also a significant gender disparity in construction employment – according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2020 only about 11% of the construction industry’s employees were women, despite making up about 47% of the nation’s workforce.

According to Marcum’s analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Opening and Labor Turnover Survey the average hourly wage nationally for construction workers in January 2021 was $32/hour, the highest it’s ever been. North Carolina is also seeing high construction worker wages, especially in areas like the Research Triangle and the Charlotte metropolitan area. According to our own interviews, this makes it more difficult for companies based in smaller counties to compete for potential employees in terms of wages. While raising wages remains a critical step towards recruiting new construction workers, other economic levers such as offering access to employer healthcare, paid vacation, and other benefits are also needed.

Other than these economic incentives, many industry advocates say that to truly bridge the gap in the labor markets, we must reframe the conversation around construction, especially with youth. This requires investment in recruitment and training initiatives at the company, community, and federal level. Prior to the pandemic, there was some concern that a lack of training, combined with its expense, could be exacerbating labor shortages. The pandemic disrupted the operations and funding of many construction training programs, and it will be an important part of recovery efforts to revisit and reaffirm government support for those programs where possible.

In general, government can play three key roles in addressing the construction labor shortage: advocate, facilitator, and funder. As an advocate, government can help dispel longstanding myths about what construction jobs entail and what wage and entrepreneurial opportunities exist for the varying occupations. In interviews with local North Carolina organizations, government was seen as a critical partner in helping to validate a new narrative around construction work.

As a facilitator, government can provide connections between existing initiatives and organize the wealth of resources available at the local, state, and federal level. In particular, government has the opportunity to facilitate conversations between organizations serving particular audiences such as women or veterans or workers who don’t speak English fluently, to other employers, workforce development boards, private companies, and even small business training centers.

As a funder, there are many creative efforts underway to educate, train, and retain potential construction workers. At this moment, the American Rescue Plan funding offers the best opportunity for catalyzing new and successful programming around this issue. Governor Cooper’s ARP budget as of May 2021 includes $150 million “to ensure the development of a 21st century workforce through access to 21st century technology” and specifically calls out funding apprenticeships for high demand fields like construction.

Apprenticeships are employer or industry-initiated ventures with their local community college and ApprenticeshipNC. At the time of writing, 25 registered building trades apprenticeships existed in North Carolina. To strengthen the foundations for a successful apprenticeship, government should continue to work closely with the NC community college system, as some may have capacity and desire to expand their building trades programs to meet increased demand, but they may not have the physical space or capital to fund that expansion. Additionally, feedback from construction employers on the ease of deciding to create a registered apprenticeship should be explored to continue to improve the process and add to the number of programs.

Increased investments by government could also include more scholarships for certification and training, especially for underrepresented or nontraditional construction workers. While it is important to focus on youth engagement, the potential career trajectories of incumbent workers also must be taken into account. Lastly, government support can be helpful in various forms for the variety of activities companies and nonprofits may choose to promote, such as design/construction contests for youth, clubs/workshops for tools learning, or youth construction academies in partnership with the YMCA.

Ultimately, addressing the labor shortage in construction, particularly with skilled trade workers, will take a coordinated effort to educate, recruit, and retain workers, requiring close interaction between companies, industry leaders, workforce development programs, schools, and government.

Many thanks to Zane Stokes, Farrah Pulliam, Jeff Parsons, and Devin Baucom for their time and conversations around this topic.

Marielle Saunders is a Master’s in City and Regional Planning candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill and a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.