|

|

What we know about COVID’s impact on affordable housing – so farBy Frank MuracaPublished January 6, 2022

While the full impact of the pandemic will take years to understand, there are clear indicators that low-income renters living in unaffordable housing bore the worst of the crisis over the past 18 months. This blog post highlights what the data and research can tell us about the pandemic’s impact on affordable housing for North Carolina renters. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), housing is considered “affordable” when housing-related costs (like rent and utilities) are no more than 30 percent of a household’s annual income. Households are considered “cost-burdened” when they spend between 30 and 50 percent of their income on housing costs, and “severely cost-burdened” when those costs exceed half their annual income. The graphic below illustrates affordability depending on the level of income in the years prior to the pandemic. For households in the lowest income bracket (those making less than 30 percent of the area median income, or around $21,000 for a family of four in North Carolina), a full 60 percent spent over half their income on housing. Among households earning between 50-80% of the median (between approximately $35,500 and $56,700 in North Carolina), over 40 percent were cost burdened. Not surprisingly, only a small percentage of those earning the median income (approximately $70,900) or higher were living in housing considered “unaffordable”. These baseline metrics are important because they show that budgets were constrained for low-income households before the onset of the pandemic. When the pandemic brought significant unemployment and income losses to these households, they were at the greatest risk of losing their housing. In the weeks immediately following issuance of social distancing guidelines, millions of jobs – from restaurant to hotel workers – disappeared. In North Carolina, the unemployment rate shot up to just under 14 percent, surpassing the unemployment rate during the height of the 2008 recession. The jobs most at-risk were those that could not be continued at home, such as occupations in the retail, restaurant, and hospitality industries, which also paid some of the lowest wages. Thus, as social distancing guidelines went into effect, low-income workers were more likely to have their hours scaled back or lose their jobs altogether. The jobs losses at the lower income range predictably affected renters the most. Research by the Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) at Harvard University indicated that about half of all renters lost income during the pandemic. Among that group, renters of color, lower-income renters, and younger renters were all more likely to lose income between March and December 2020. To help cover housing and other costs, 1 in 4 renters “substantially depleted their savings.” Others cut back on discretionary spending or reached out to friends and families for help. To help combat the crisis, the State of North Carolina and some local governments set up rental assistance programs to help with rent and utility payments. As of December 2021, the North Carolina Housing Opportunities and Prevention of Evictions (HOPE) program managed by the N.C. Office of Recovery & Resiliency has awarded $676 million to 145,000 households. Fewer affordable units after the pandemic We know that severely cost-burdened renters – who live in housing that costs over half their annual income – were adversely affected by the job losses and were therefore less likely to make rental payments on time. How did landlords respond? According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, just at the time that many renter households needed lower rents, landlords increased prices in the face of greater demand. Data from CoStar showed that rents for more expensive, high-end apartments dropped in metro areas across the U.S between the 2019 and the end 2020. According to one analysis by the Washington Post, “with covid-19 largely shutting down the perks of city life, many tenants who had the means to leave did so. Higher-wage workers who were juggling remote work and virtual school sought out more space, often purchasing a house in the [suburbs].” According to a recent JCHS survey of 2,500 rental property owners across ten U.S. cities, landlord business practices during the crisis were apparently different across neighborhoods. For example, in predominantly white neighborhoods, landlords were more likely to forgive or decrease rents. By comparison, landlords operating properties in neighborhoods of color were more likely to evict tenants or charge fees. Loss of income, rising rents, and landlords’ differing attitudes towards tenants with late payments amplified the effects of the crisis for low-income renters. While the number of jobs and other economic indicators have rebounded since March 2020, the cost of housing continues to increase across North Carolina. Recent data from Apartment List shows double digit rent growth across all major metro areas, indicating a continued need for affordable housing options for low-income renters. Local governments can address local housing needs through the preservation or development of affordable housing. The Development Finance Initiative (DFI), based in the UNC School of Government, works with communities across the state to identify their local housing needs, to identify sites for preservation or new construction, and to explore creative financing to catalyze housing development. To learn more about DFI’s work in affordable housing, visit: https://dfi.sog.unc.edu/affordable-housing/. Frank Muraca is a Real Estate Development Analyst with the Development Finance Initiative at the UNC School of Government. |

Published January 6, 2022 By Frank Muraca

The economic fallout from COVID-19 magnified many of the existing challenges faced by North Carolina communities such as access to open space or the capacity of the local health care systems. Among these issues, the crisis highlighted how stable and affordable housing is essential to the well-being of local communities. In developing policy responses to the pandemic, federal, state, and local governments have placed affordable housing front and center.

The economic fallout from COVID-19 magnified many of the existing challenges faced by North Carolina communities such as access to open space or the capacity of the local health care systems. Among these issues, the crisis highlighted how stable and affordable housing is essential to the well-being of local communities. In developing policy responses to the pandemic, federal, state, and local governments have placed affordable housing front and center.

While the full impact of the pandemic will take years to understand, there are clear indicators that low-income renters living in unaffordable housing bore the worst of the crisis over the past 18 months. This blog post highlights what the data and research can tell us about the pandemic’s impact on affordable housing for North Carolina renters.

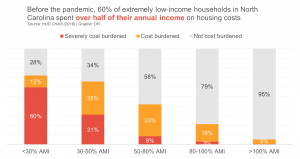

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), housing is considered “affordable” when housing-related costs (like rent and utilities) are no more than 30 percent of a household’s annual income. Households are considered “cost-burdened” when they spend between 30 and 50 percent of their income on housing costs, and “severely cost-burdened” when those costs exceed half their annual income.

The graphic below illustrates affordability depending on the level of income in the years prior to the pandemic. For households in the lowest income bracket (those making less than 30 percent of the area median income, or around $21,000 for a family of four in North Carolina), a full 60 percent spent over half their income on housing. Among households earning between 50-80% of the median (between approximately $35,500 and $56,700 in North Carolina), over 40 percent were cost burdened. Not surprisingly, only a small percentage of those earning the median income (approximately $70,900) or higher were living in housing considered “unaffordable”.

These baseline metrics are important because they show that budgets were constrained for low-income households before the onset of the pandemic. When the pandemic brought significant unemployment and income losses to these households, they were at the greatest risk of losing their housing.

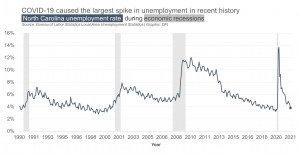

In the weeks immediately following issuance of social distancing guidelines, millions of jobs – from restaurant to hotel workers – disappeared. In North Carolina, the unemployment rate shot up to just under 14 percent, surpassing the unemployment rate during the height of the 2008 recession.

The jobs most at-risk were those that could not be continued at home, such as occupations in the retail, restaurant, and hospitality industries, which also paid some of the lowest wages. Thus, as social distancing guidelines went into effect, low-income workers were more likely to have their hours scaled back or lose their jobs altogether.

The jobs losses at the lower income range predictably affected renters the most. Research by the Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS) at Harvard University indicated that about half of all renters lost income during the pandemic. Among that group, renters of color, lower-income renters, and younger renters were all more likely to lose income between March and December 2020. To help cover housing and other costs, 1 in 4 renters “substantially depleted their savings.” Others cut back on discretionary spending or reached out to friends and families for help.

To help combat the crisis, the State of North Carolina and some local governments set up rental assistance programs to help with rent and utility payments. As of December 2021, the North Carolina Housing Opportunities and Prevention of Evictions (HOPE) program managed by the N.C. Office of Recovery & Resiliency has awarded $676 million to 145,000 households.

Fewer affordable units after the pandemic

We know that severely cost-burdened renters – who live in housing that costs over half their annual income – were adversely affected by the job losses and were therefore less likely to make rental payments on time. How did landlords respond?

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, just at the time that many renter households needed lower rents, landlords increased prices in the face of greater demand.

Data from CoStar showed that rents for more expensive, high-end apartments dropped in metro areas across the U.S between the 2019 and the end 2020. According to one analysis by the Washington Post, “with covid-19 largely shutting down the perks of city life, many tenants who had the means to leave did so. Higher-wage workers who were juggling remote work and virtual school sought out more space, often purchasing a house in the [suburbs].”

According to a recent JCHS survey of 2,500 rental property owners across ten U.S. cities, landlord business practices during the crisis were apparently different across neighborhoods. For example, in predominantly white neighborhoods, landlords were more likely to forgive or decrease rents. By comparison, landlords operating properties in neighborhoods of color were more likely to evict tenants or charge fees. Loss of income, rising rents, and landlords’ differing attitudes towards tenants with late payments amplified the effects of the crisis for low-income renters.

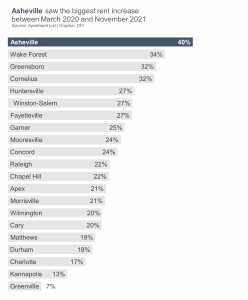

While the number of jobs and other economic indicators have rebounded since March 2020, the cost of housing continues to increase across North Carolina. Recent data from Apartment List shows double digit rent growth across all major metro areas, indicating a continued need for affordable housing options for low-income renters.

Local governments can address local housing needs through the preservation or development of affordable housing. The Development Finance Initiative (DFI), based in the UNC School of Government, works with communities across the state to identify their local housing needs, to identify sites for preservation or new construction, and to explore creative financing to catalyze housing development. To learn more about DFI’s work in affordable housing, visit: https://dfi.sog.unc.edu/affordable-housing/.

Frank Muraca is a Real Estate Development Analyst with the Development Finance Initiative at the UNC School of Government.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.