|

|

Student Corner: An Innovation District in Downtown Durham: Will It Mean Gentrification? Not Necessarily…By CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished July 13, 2017

The Durham.ID office buildings will together total 350,000 square feet of office, research, retail, and restaurant space on land that was previously underutilized as a parking lot. With over $100 million in new construction on 15 acres, the district is projected for completion in spring or summer 2018. Even Durham city and county governments are getting in on the ground floor of Durham.ID; they are contributing over $5 million toward the cost of the parking deck, which will supplement parking for nearby downtown attractions. Clearly, a new Durham is dawning, as echoed by Adam Sichol, co-founder and managing partner of Boston-based Longfellow. Sichol stated at the groundbreaking event, “Today we’re betting on the future of Durham and its people.” But will it provide a return on investment? And what will it mean for Durham residents? According to the Durham Innovation District Master Plan, the project “is intended to become part of the fabric of Downtown.” As explained by Scott Selig, associate vice president of real estate for Duke University, downtown Durham is entering a phase of new construction that will shape the city’s experience and economy. Drawing on the success of Research Triangle Park (RTP), as explored by the Brookings Institution, Durham.ID has the commonly-accepted pieces of the puzzle that lend itself to a successful innovation district – a distinct geographic area, an anchor institution (e.g., research university of research-oriented medial hospital) and the “cluster and connection” with other companies, startups, and business incubators. The success of RTP should mean success for Durham.ID, as asserted by Jessica Brock, Longfellow Real Estate Partners’ managing director for its new Durham office. Brock states, “The Research Triangle Park has obviously been extremely successful attracting companies… At the same time, [Durham’s] market has lacked an urban alternative for life sciences companies. A more diverse market means homes for more companies. And a rising tide lifts all boats.” But does this rising tide truly life up all boats? Or just some?  As explored by Jennifer Vey in CityLab, the conception of an innovation district is often accompanied by fears of displacement, by residents and businesses alike. Innovation districts lend themselves to rising tensions and difficult discussions regarding the desire for economic growth and the suspicion that there will be clear winner and losers in this innovation-related growth. Technology and innovation has undoubtedly caused some instances of economic disparity and gentrification in the U.S., as currently experienced in Silicon Valley and the Bay Area. However, Vey argues, it is the rise in concentrated poverty, and not gentrification, which is widening the gap between those are succeeding in this innovation economy, and those who are not. Vey sees the growth and revitalization that accompanies innovation districts, such as Durham.ID, as being “a long time coming” for residents. The urban nature of the innovation economy means that the firms’ demand for proximity is matched with their workers’ desire for authenticity and walkability. These complementary demands encourage districts with both urban density and economic vitality which, in turn, create revenues. These additional revenues can, in turn, be reinvested in education, infrastructure, neighborhood renewal, and other community development initiatives. Thus, innovation districts can provide a return on investment to both businesses and residents, and create a rising tide that lifts all boats. Vey argues that innovation districts should capitalize on the opportunity to engage residents and businesses that have been historically excepted from economic growth. As stated by Kyle Chaka, “enlivening a city’s brand is tempting, but energizing its entire population is even better.” Gentrification assumes some degree of change, which inherently accompanies innovation districts and the public and private development spurred by their creation. However, this change can be constructively-employed as a catalyst for community engagement and involvement towards the shaping of their current and future community. Durham.ID could indeed be the district “where innovation makes its home downtown – tapping into a long tradition of entrepreneurship, and the energy of a unique creative class.” Stay tuned, Bull City. For more information on innovation districts, see CED in NC’s previous blog post on Re-visioning the Research Triangle Park: How Innovation Districts Are Inspiring New Approaches to Local Economic Development Kaley Huston is a Master’s candidate in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning specializing in Land Use and Environmental Planning and a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. She is also pursuing a Natural Hazards Resilience Certificate in partnership with the Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence at UNC. |

Published July 13, 2017 By CED Program Interns & Students

On March 16, 2017, Longfellow Real Estate Partners, in partnership with Duke University and Measurement Inc., broke ground on the first phase of new construction on the Durham Innovation District, or Durham.ID, in downtown. Durham.ID describes itself as “1.7M square feet of possibility nestled among lab rats, hipster, locavores, artists, pre-revenue-work-all-night start-up junkies, and a few thousand rabid Bulls and Blue Devils Fans.” Tenants, including Duke University and Duke Clinical Research Institute, will be housed in two seven-story office buildings located at the corner of Morris and Hunt streets, with access to a 1,200-vehicle, eight-story parking deck.

On March 16, 2017, Longfellow Real Estate Partners, in partnership with Duke University and Measurement Inc., broke ground on the first phase of new construction on the Durham Innovation District, or Durham.ID, in downtown. Durham.ID describes itself as “1.7M square feet of possibility nestled among lab rats, hipster, locavores, artists, pre-revenue-work-all-night start-up junkies, and a few thousand rabid Bulls and Blue Devils Fans.” Tenants, including Duke University and Duke Clinical Research Institute, will be housed in two seven-story office buildings located at the corner of Morris and Hunt streets, with access to a 1,200-vehicle, eight-story parking deck.

The Durham.ID office buildings will together total 350,000 square feet of office, research, retail, and restaurant space on land that was previously underutilized as a parking lot. With over $100 million in new construction on 15 acres, the district is projected for completion in spring or summer 2018. Even Durham city and county governments are getting in on the ground floor of Durham.ID; they are contributing over $5 million toward the cost of the parking deck, which will supplement parking for nearby downtown attractions. Clearly, a new Durham is dawning, as echoed by Adam Sichol, co-founder and managing partner of Boston-based Longfellow. Sichol stated at the groundbreaking event, “Today we’re betting on the future of Durham and its people.” But will it provide a return on investment? And what will it mean for Durham residents?

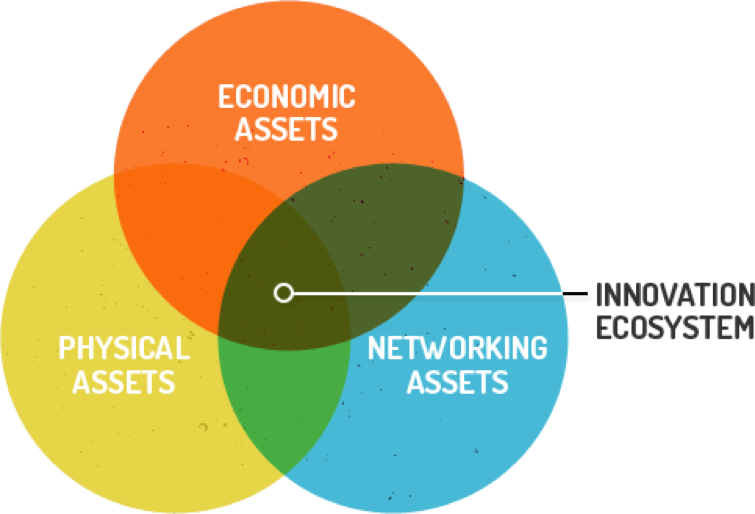

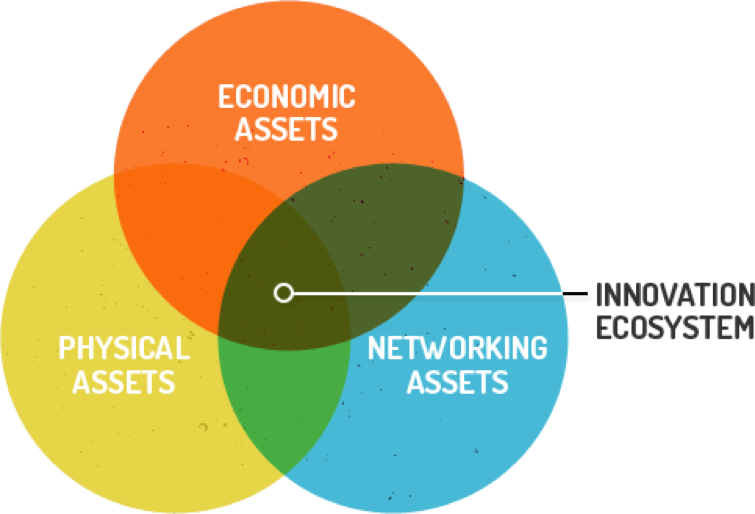

According to the Durham Innovation District Master Plan, the project “is intended to become part of the fabric of Downtown.” As explained by Scott Selig, associate vice president of real estate for Duke University, downtown Durham is entering a phase of new construction that will shape the city’s experience and economy. Drawing on the success of Research Triangle Park (RTP), as explored by the Brookings Institution, Durham.ID has the commonly-accepted pieces of the puzzle that lend itself to a successful innovation district – a distinct geographic area, an anchor institution (e.g., research university of research-oriented medial hospital) and the “cluster and connection” with other companies, startups, and business incubators. The success of RTP should mean success for Durham.ID, as asserted by Jessica Brock, Longfellow Real Estate Partners’ managing director for its new Durham office. Brock states, “The Research Triangle Park has obviously been extremely successful attracting companies… At the same time, [Durham’s] market has lacked an urban alternative for life sciences companies. A more diverse market means homes for more companies. And a rising tide lifts all boats.” But does this rising tide truly life up all boats? Or just some?

As explored by Jennifer Vey in CityLab, the conception of an innovation district is often accompanied by fears of displacement, by residents and businesses alike. Innovation districts lend themselves to rising tensions and difficult discussions regarding the desire for economic growth and the suspicion that there will be clear winner and losers in this innovation-related growth. Technology and innovation has undoubtedly caused some instances of economic disparity and gentrification in the U.S., as currently experienced in Silicon Valley and the Bay Area. However, Vey argues, it is the rise in concentrated poverty, and not gentrification, which is widening the gap between those are succeeding in this innovation economy, and those who are not.

Vey sees the growth and revitalization that accompanies innovation districts, such as Durham.ID, as being “a long time coming” for residents. The urban nature of the innovation economy means that the firms’ demand for proximity is matched with their workers’ desire for authenticity and walkability. These complementary demands encourage districts with both urban density and economic vitality which, in turn, create revenues. These additional revenues can, in turn, be reinvested in education, infrastructure, neighborhood renewal, and other community development initiatives. Thus, innovation districts can provide a return on investment to both businesses and residents, and create a rising tide that lifts all boats.

Vey argues that innovation districts should capitalize on the opportunity to engage residents and businesses that have been historically excepted from economic growth. As stated by Kyle Chaka, “enlivening a city’s brand is tempting, but energizing its entire population is even better.” Gentrification assumes some degree of change, which inherently accompanies innovation districts and the public and private development spurred by their creation. However, this change can be constructively-employed as a catalyst for community engagement and involvement towards the shaping of their current and future community. Durham.ID could indeed be the district “where innovation makes its home downtown – tapping into a long tradition of entrepreneurship, and the energy of a unique creative class.” Stay tuned, Bull City.

For more information on innovation districts, see CED in NC’s previous blog post on Re-visioning the Research Triangle Park: How Innovation Districts Are Inspiring New Approaches to Local Economic Development

Kaley Huston is a Master’s candidate in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of City and Regional Planning specializing in Land Use and Environmental Planning and a Community Revitalization Fellow with the Development Finance Initiative. She is also pursuing a Natural Hazards Resilience Certificate in partnership with the Coastal Resilience Center of Excellence at UNC.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.