|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Student Corner: Mega Sites: Part I – Economic Body-BuildingBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished May 30, 2013

In order to add mass to its industrial recruitment muscle, North Carolina is supplementing its economic development diet with a healthy dose of “mega sites” that it hopes will tip the scales with prospective manufacturers. “Mega” Defined Mega sites are broad tracts of land—1000+ acres—prepared to suit the needs of a future large-scale plant. Size matters because the manufacturer will be locating all their production on the site. They want to make sure there is a sufficient buffer between them and other neighbors and they may need space for just-in-time suppliers, as well as the option to expand their footprint in the future. But that is not the end of it. A mega site should also have access to utilities (water, sewer, energy, telecommunications), transportation networks (highway and rail), and a skilled workforce to support a large industrial plant. There are no national standards for mega site certification. However, several site selection consultants offer their own certification, as do economic development authorities. The Tennessee Valley Authority launched the first mega site certification program in 2004. TVA has since prepared eight mega sites certified by a third-party, four of which have been acquired by automotive manufacturers. The certification gives industrial users confidence that the site can be made ready within a reasonable cost and timeframe. The N.C. Department of Commerce has run a program to certify small to medium industrial sites since 2001. The program covers several steps of the due diligence that a potential client would want to see before moving into a site:

The Department of Commerce lists nine sites in North Carolina of 1000 acres or more that have railway access (see table). Currently, none of them are “certified.”

Competing for Site Selection In 2012, the N.C. Department of Commerce saw that other state governments were building inventories of certified mega sites from which potential manufacturers could make their selection. To that end, the Department of Commerce issued a $5-million request for proposals from local governments and non-profits seeking to prepare mega sites. In January, the Department of Commerce awarded Davidson, Edgecombe and Randolph counties $1.67 million grants to each begin acquiring land. Meanwhile, several similar sites are in various stages of planning across the state: in Chatham County (1,400 acres), Alamance County (1,425 acres), and Montgomery and Moore counties (3,000 acres), with the latter being the furthest along in plans. Mega Boost to Jobs The intended outcome of landing an anchor tenant at a mega site is to boost local employment. The plants themselves are huge investments that create temporary construction jobs for many years. Ongoing plant operations will then directly employ thousands of workers and indirectly generate many more jobs through the parts suppliers and service providers that locate near the plant. In the case of the Randolph County mega site, officials estimate an auto assembly plant would directly create 2000 jobs[1]. Economic impact studies of other industrial parks support such projections:

Stay tuned for Part II of this report in which we’ll unpack the risks of public investment in mega sites for industrial recruitment. Peter Cvelich is a UNC-Chapel Hill graduate student pursuing an MBA and a master’s in City and Regional Planning. He is currently working with the Development Finance Initiative.

[1] Barron, Richard M. “Triad executives seek ‘game changer’ to bring auto plant.” Winston-Salem Journal. March 21, 2013. [2] “Economic Impact Analysis for the Planned Development of an Industrial Park on the economy of Jefferson County.” January 2013. Younger Associates. [3] “Economic Impact of the Kingman Airport Industrial Park.” September 2005. Coffman Associates and W.P. Carey School of Business Arizona State University. [4] “Mid-Atlantic Advanced Manufacturing Center Receives Two Additional Grants.” MAMACVA.Com. January 29, 2013. [5] “Baldwin County Mega-Site: Project Identification Template and Instructions.” Coastal Recovery Commission of Alabama Infrastructure Sub-Committee. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Published May 30, 2013 By CED Program Interns & Students

North Carolina is one of the few Southeastern states that do not host a major auto assembly plant. But for how much longer? With automotive manufacturing employment on the rise again, economic development officials are preparing to be the preferred destination for the next carmaker.

North Carolina is one of the few Southeastern states that do not host a major auto assembly plant. But for how much longer? With automotive manufacturing employment on the rise again, economic development officials are preparing to be the preferred destination for the next carmaker.

In order to add mass to its industrial recruitment muscle, North Carolina is supplementing its economic development diet with a healthy dose of “mega sites” that it hopes will tip the scales with prospective manufacturers.

“Mega” Defined

Mega sites are broad tracts of land—1000+ acres—prepared to suit the needs of a future large-scale plant. Size matters because the manufacturer will be locating all their production on the site. They want to make sure there is a sufficient buffer between them and other neighbors and they may need space for just-in-time suppliers, as well as the option to expand their footprint in the future. But that is not the end of it. A mega site should also have access to utilities (water, sewer, energy, telecommunications), transportation networks (highway and rail), and a skilled workforce to support a large industrial plant.

There are no national standards for mega site certification. However, several site selection consultants offer their own certification, as do economic development authorities. The Tennessee Valley Authority launched the first mega site certification program in 2004. TVA has since prepared eight mega sites certified by a third-party, four of which have been acquired by automotive manufacturers. The certification gives industrial users confidence that the site can be made ready within a reasonable cost and timeframe.

The N.C. Department of Commerce has run a program to certify small to medium industrial sites since 2001. The program covers several steps of the due diligence that a potential client would want to see before moving into a site:

- Confirming industrial land use designation

- Completing an environmental assessment (phase 1)

- Studying the land for construction suitability

- Confirming available public utilities

- Preparing a site plan

- Projecting development costs

- Providing clear title and price information

The Department of Commerce lists nine sites in North Carolina of 1000 acres or more that have railway access (see table). Currently, none of them are “certified.”

| Site | County | Acres | Former Use |

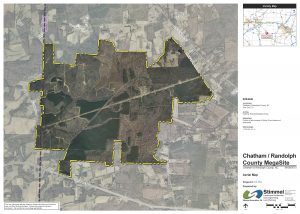

| Chatham-Randolph Mega site | Chatham | 1,704 | Agricultural |

| GIPH | Hertford | 1,700 | Idle |

| Hearts Delight Site | Bertie | 1,900 | Idle |

| Kingsboro-Rose Mega Site | Edgecombe | 1,225 | Agriculture |

| Laurinburg-Maxton Airport Indus. Park | Scotland | 2,000 | Military Base |

| Mid-Atlantic Logistics Center | Brunswick | 1,000 | Wooded Land |

| Pine Hills Industrial Park | Richmond | 1,500 | Open Land |

| Tanglewood Mega Site | Pasquotank | 5,915 | Agricultural |

| Verona Plantation | Northampton | 3,943 | Agricultural/Residential |

| Source: AccessNC database. March 25, 2013. | |||

Competing for Site Selection

In 2012, the N.C. Department of Commerce saw that other state governments were building inventories of certified mega sites from which potential manufacturers could make their selection.

To that end, the Department of Commerce issued a $5-million request for proposals from local governments and non-profits seeking to prepare mega sites. In January, the Department of Commerce awarded Davidson, Edgecombe and Randolph counties $1.67 million grants to each begin acquiring land.

Meanwhile, several similar sites are in various stages of planning across the state: in Chatham County (1,400 acres), Alamance County (1,425 acres), and Montgomery and Moore counties (3,000 acres), with the latter being the furthest along in plans.

Mega Boost to Jobs

The intended outcome of landing an anchor tenant at a mega site is to boost local employment. The plants themselves are huge investments that create temporary construction jobs for many years. Ongoing plant operations will then directly employ thousands of workers and indirectly generate many more jobs through the parts suppliers and service providers that locate near the plant.

In the case of the Randolph County mega site, officials estimate an auto assembly plant would directly create 2000 jobs[1]. Economic impact studies of other industrial parks support such projections:

- In Jefferson County, TN, a 1860-acre mega site for an auto assembly plant was estimated to create 7,000 jobs during the construction of the plant and 4,983 direct and indirect jobs through the ongoing operations of the plant, according to a study commissioned by the county[2].

- In Mohave County, AZ, the 1000-acre Kingman Airport Industrial Park is home to more than 50 businesses. These businesses directly produced 2,058 jobs and $357 million in business revenues, plus led to indirect impact of 3,300 jobs and $262 million in revenues, according to a study by Arizona State University[3].

- In Greenville County, VA, the 1,545-acre certified Mid-Atlantic Advanced Manufacturing Center is projected to create 2,487 to 3,297 permanent jobs depending on the type of industrial user that ultimately occupies the site[4].

- In Baldwin County, AL, the Coastal Recovery Commission estimated at least 3,000 permanent jobs resulting from development of a 3,000-acre mega site into an auto plant[5].

Stay tuned for Part II of this report in which we’ll unpack the risks of public investment in mega sites for industrial recruitment.

[1] Barron, Richard M. “Triad executives seek ‘game changer’ to bring auto plant.” Winston-Salem Journal. March 21, 2013.

[2] “Economic Impact Analysis for the Planned Development of an Industrial Park on the economy of Jefferson County.” January 2013. Younger Associates.

[3] “Economic Impact of the Kingman Airport Industrial Park.” September 2005. Coffman Associates and

W.P. Carey School of Business Arizona State University.

[4] “Mid-Atlantic Advanced Manufacturing Center Receives Two Additional Grants.” MAMACVA.Com. January 29, 2013.

[5] “Baldwin County Mega-Site: Project Identification Template and Instructions.” Coastal Recovery Commission of Alabama Infrastructure Sub-Committee.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.