|

|

Student Corner: How a Local Government Loan Can Make a Revitalization Project PossibleBy CED Program Interns & StudentsPublished September 4, 2015

Her staff estimates that the building will cost about $620,000 to acquire and redevelop into office space. This includes hard costs related to roof repair and general construction as well as soft costs such as architectural, engineering, and legal services. The town isn’t ready to make an investment of that size, but perhaps a private developer could be convinced to take on the project. She turns to a graduate student team in the Community Revitalization course at the School of Government for assistance with evaluating the financial feasibility of redevelopment. The student team approaches the project from the perspective of a private developer. The team determines that the bulk of the redevelopment costs can be financed through a traditional bank loan. The team assumes that a private developer could receive a primary loan of about $215,000, or 75 percent of the expected value of the building once it is fully leased to tenants. The team also assumes that, because the building is on the National Register of Historic Places, the project will qualify for historic rehabilitation tax credits that will contribute around $160,000 in equity for the project. The use of tax credits means that the building must be held for the first six years after it’s developed, but the student team’s calculations assume that it would then be sold, resulting in a large amount of income after six years. Also, the use of tax credits allows the developer’s fee to be partially reimbursed—it is one of many “qualified rehabilitation expenses.” The team assumes that the developer’s fee would be 20 percent of the total cost of acquisition and development, or $87,000. When using historic tax credits, it is customary for 80 percent of the developer’s fee to be deferred, which would make $70,000 of that fee available as upfront equity. In addition, officials have told the team that a group of local businesspeople, excited to play a role in bringing the manufacturing building back to life, have agreed to make a $30,000 loan to replace the roof. Here’s a breakdown of these sources of capital: Even with tax credits, though, the project’s return (known as IRR, or internal rate of return) of 13 percent is probably too low to attract many traditional investors; most will be looking for at least 15 percent, if not higher. Still, community-minded investors might be willing to accept those lower returns in order to participate in a local revitalization project. Yet the project’s need for nearly $150,000 in equity makes it too large of a commitment for any local residents. In a group brainstorming session, a team member wonders whether the Town could make a grant to the project. A grant, by decreasing the amount of equity required, might help attract investors. Manager Perez has told the team that the same group of local businesspeople who are loaning money for roof repairs are also interested in investing, but they’re not able to contribute more than $100,000. A $50,000 grant from the Town, though, which would lower the equity requirement to $96,000 and increase the IRR to an attractive 24 percent, could make this project happen. However, the attorney advising the student team points out that a grant is not legally permissible for this project. (For more information on the legal concerns related to providing a grant, see this post.) The team recalls from a post in the CED in NC blog that when grants are not permissible, local governments can offer a loan instead at the market rate of interest (what a private lender would charge for the same loan). They remember another post about mezzanine debt, which is a way to fill the gap between equity and debt financing in projects like these. They sit down to figure out what a mezzanine loan from the local government could do for the project. Their research reveals that the market rate of interest for a secondary loan like this is at least 10 percent. A rate of 10 percent or more will also ensure that the developer will seek to pay off this loan first. They calculate that by making an interest-only mezzanine loan with 10 percent interest—and a balloon repayment due when the building is sold after six years—the Town can increase the project’s IRR, or returns, and lower the amount of equity needed. For example, a $30,000 loan would increase the IRR from 13 percent to 14 percent. But the payments on this $30,000 loan, even though they would not include principal for six years, would still be too high for the project’s modest rental income to cover. This concept is usually represented in a ratio called debt service coverage ratio, where a 1.0 ratio means the project income exactly covers the debt payments. Most lenders typically require ratios of around 1.25 before they will make a loan to a project, and the higher the ratio, the better. While a mezzanine lender such as a local government or community-minded resident will often be willing to stomach the risk of a lower debt service coverage ratio, in the Town’s case, a loan larger than $30,000 would produce a negative ratio: the project isn’t expected to have the cash flows necessary to pay even the interest on this loan. The team knows that it will be easier for the town to attract a primary investor if the project requires less equity and has higher returns, but they’re not sure that a one percentage point increase in IRR is worth a $30,000 loan. They wonder what deferring both interest and principal payments until a year six sale would do for the project. Team members imagine that in this scenario the mezzanine loan would increase the IRR more forcefully than in the previous situation, decrease the amount of equity required, and have no impact on the ability of the project to pay its debts with its projected cash flows. Such a loan, made by a public-minded lender or the Town itself, could be transformative for the project. They run the numbers and see that the same $30,000 mezzanine loan, with both interest and principal payments deferred until the building is sold, would push project returns from 13 to 15 percent, while decreasing the amount of required equity to $116,000—and the project would maintain a healthy debt service coverage ratio of 1.25. What’s more, a $40,000 to $50,000 loan, which would lower the equity requirement sufficiently for local investors to take part, would increase the IRR to over 15 percent. The student team presents its analysis to Manager Perez and her staff. Perez is hopeful. She thinks that the reward would be worth the risk that the town would assume by making a loan. She also believes that a loan to the project is a more responsible—and much more feasible—form of participation for the local government than a legally questionable grant. Furthermore, if a high interest rate loan is sufficient to make the project feasible, a subsidy or grant isn’t even necessary, which is a legally significant point. A week later, Perez—armed with the team’s report that shows the transformative potential and the impact of grants and mezzanine loans on the project—confidently walks her councilmembers through the process that they can undertake to revitalize the historic manufacturing building. If your community is interested in submitting a revitalization project for possible evaluation by a graduate student team, please submit the Student Team Revitalization Project Submission Webform, or contact Tyler Mulligan or Christy Raulli. Andrew Trump is a student in the Master of City and Regional Planning and Master of Public Administration programs at UNC-Chapel Hill and a fellow at the Development Finance Initiative.

|

Published September 4, 2015 By CED Program Interns & Students

An historic manufacturing building in the town of Sunrise, North Carolina, is in disrepair. There are holes in the roof, standing water in the basement. Residents treasure the 3,500 square foot building and public officials want to see it redeveloped and contribute to the revitalization of their historic downtown, but they haven’t been able to figure out how. At the urging of councilmembers, Town Manager Estella Perez makes the project a priority.

An historic manufacturing building in the town of Sunrise, North Carolina, is in disrepair. There are holes in the roof, standing water in the basement. Residents treasure the 3,500 square foot building and public officials want to see it redeveloped and contribute to the revitalization of their historic downtown, but they haven’t been able to figure out how. At the urging of councilmembers, Town Manager Estella Perez makes the project a priority.

Her staff estimates that the building will cost about $620,000 to acquire and redevelop into office space. This includes hard costs related to roof repair and general construction as well as soft costs such as architectural, engineering, and legal services. The town isn’t ready to make an investment of that size, but perhaps a private developer could be convinced to take on the project. She turns to a graduate student team in the Community Revitalization course at the School of Government for assistance with evaluating the financial feasibility of redevelopment.

The student team approaches the project from the perspective of a private developer. The team determines that the bulk of the redevelopment costs can be financed through a traditional bank loan. The team assumes that a private developer could receive a primary loan of about $215,000, or 75 percent of the expected value of the building once it is fully leased to tenants.

The team also assumes that, because the building is on the National Register of Historic Places, the project will qualify for historic rehabilitation tax credits that will contribute around $160,000 in equity for the project. The use of tax credits means that the building must be held for the first six years after it’s developed, but the student team’s calculations assume that it would then be sold, resulting in a large amount of income after six years.

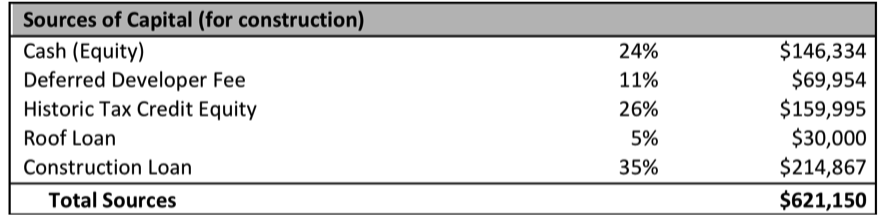

Also, the use of tax credits allows the developer’s fee to be partially reimbursed—it is one of many “qualified rehabilitation expenses.” The team assumes that the developer’s fee would be 20 percent of the total cost of acquisition and development, or $87,000. When using historic tax credits, it is customary for 80 percent of the developer’s fee to be deferred, which would make $70,000 of that fee available as upfront equity. In addition, officials have told the team that a group of local businesspeople, excited to play a role in bringing the manufacturing building back to life, have agreed to make a $30,000 loan to replace the roof.

Here’s a breakdown of these sources of capital:

Even with tax credits, though, the project’s return (known as IRR, or internal rate of return) of 13 percent is probably too low to attract many traditional investors; most will be looking for at least 15 percent, if not higher. Still, community-minded investors might be willing to accept those lower returns in order to participate in a local revitalization project. Yet the project’s need for nearly $150,000 in equity makes it too large of a commitment for any local residents.

In a group brainstorming session, a team member wonders whether the Town could make a grant to the project. A grant, by decreasing the amount of equity required, might help attract investors. Manager Perez has told the team that the same group of local businesspeople who are loaning money for roof repairs are also interested in investing, but they’re not able to contribute more than $100,000. A $50,000 grant from the Town, though, which would lower the equity requirement to $96,000 and increase the IRR to an attractive 24 percent, could make this project happen. However, the attorney advising the student team points out that a grant is not legally permissible for this project. (For more information on the legal concerns related to providing a grant, see this post.)

The team recalls from a post in the CED in NC blog that when grants are not permissible, local governments can offer a loan instead at the market rate of interest (what a private lender would charge for the same loan). They remember another post about mezzanine debt, which is a way to fill the gap between equity and debt financing in projects like these. They sit down to figure out what a mezzanine loan from the local government could do for the project.

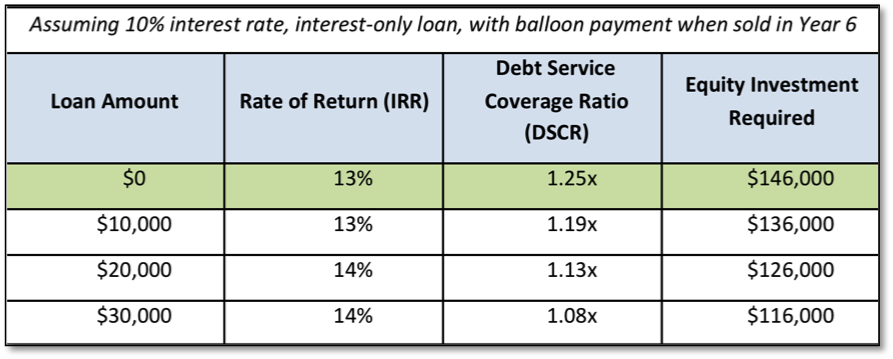

Their research reveals that the market rate of interest for a secondary loan like this is at least 10 percent. A rate of 10 percent or more will also ensure that the developer will seek to pay off this loan first. They calculate that by making an interest-only mezzanine loan with 10 percent interest—and a balloon repayment due when the building is sold after six years—the Town can increase the project’s IRR, or returns, and lower the amount of equity needed. For example, a $30,000 loan would increase the IRR from 13 percent to 14 percent.

But the payments on this $30,000 loan, even though they would not include principal for six years, would still be too high for the project’s modest rental income to cover. This concept is usually represented in a ratio called debt service coverage ratio, where a 1.0 ratio means the project income exactly covers the debt payments. Most lenders typically require ratios of around 1.25 before they will make a loan to a project, and the higher the ratio, the better. While a mezzanine lender such as a local government or community-minded resident will often be willing to stomach the risk of a lower debt service coverage ratio, in the Town’s case, a loan larger than $30,000 would produce a negative ratio: the project isn’t expected to have the cash flows necessary to pay even the interest on this loan.

The team knows that it will be easier for the town to attract a primary investor if the project requires less equity and has higher returns, but they’re not sure that a one percentage point increase in IRR is worth a $30,000 loan.

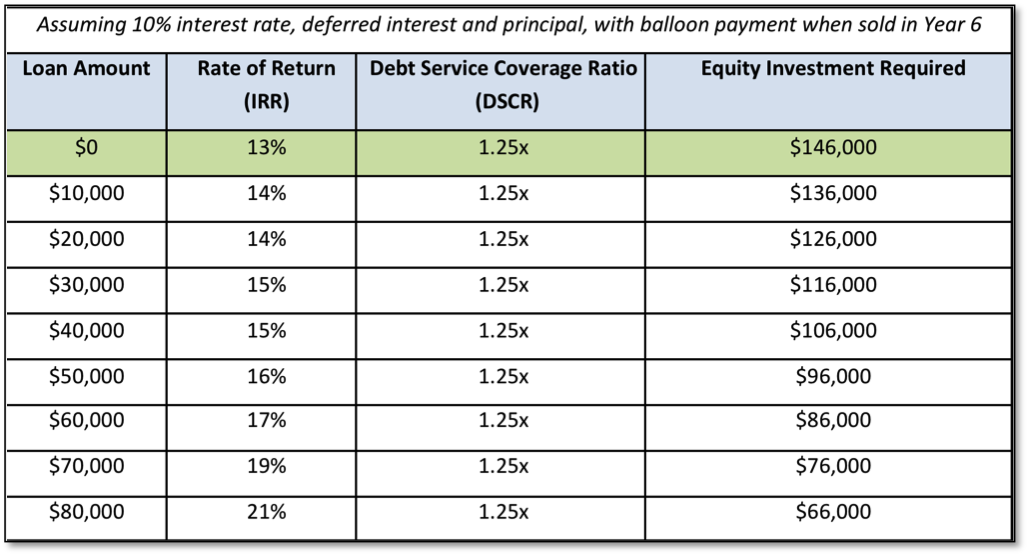

They wonder what deferring both interest and principal payments until a year six sale would do for the project. Team members imagine that in this scenario the mezzanine loan would increase the IRR more forcefully than in the previous situation, decrease the amount of equity required, and have no impact on the ability of the project to pay its debts with its projected cash flows. Such a loan, made by a public-minded lender or the Town itself, could be transformative for the project.

They run the numbers and see that the same $30,000 mezzanine loan, with both interest and principal payments deferred until the building is sold, would push project returns from 13 to 15 percent, while decreasing the amount of required equity to $116,000—and the project would maintain a healthy debt service coverage ratio of 1.25.

What’s more, a $40,000 to $50,000 loan, which would lower the equity requirement sufficiently for local investors to take part, would increase the IRR to over 15 percent.

The student team presents its analysis to Manager Perez and her staff. Perez is hopeful. She thinks that the reward would be worth the risk that the town would assume by making a loan. She also believes that a loan to the project is a more responsible—and much more feasible—form of participation for the local government than a legally questionable grant. Furthermore, if a high interest rate loan is sufficient to make the project feasible, a subsidy or grant isn’t even necessary, which is a legally significant point.

A week later, Perez—armed with the team’s report that shows the transformative potential and the impact of grants and mezzanine loans on the project—confidently walks her councilmembers through the process that they can undertake to revitalize the historic manufacturing building.

If your community is interested in submitting a revitalization project for possible evaluation by a graduate student team, please submit the Student Team Revitalization Project Submission Webform, or contact Tyler Mulligan or Christy Raulli.

Andrew Trump is a student in the Master of City and Regional Planning and Master of Public Administration programs at UNC-Chapel Hill and a fellow at the Development Finance Initiative.

Author(s)

Tagged Under

This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational Copyright ©️ 2009 to present School of Government at the University of North Carolina. All rights reserved. use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.